Polycentric Global Missions

Understanding Polycentric Mission

Any discussion of the future of ‘polycentrism’ must begin with the evolution of its definition as applied to Christian mission. In 2009 Kirsteen Kim drew attention to geographic centres of influence, ‘from one centre (in the West, for example) to “the rest”’.1 In 2016 Kirk Franklin and Nelus Niemand highlighted the global character of Christianity, having progressed ‘from being solely a “EuroAmerican religion” to a global one’.2 Patrick Fung called it ‘from all nations to all nations’.3 Place mattered.

The discourse matured, however, as Allen Yeh explored polycentricity as ‘from everyone to everywhere.’4 Geography was still important, but not exclusive. The ‘who’ that was going was also critical. Culture, platform, context, gifting, capacities—these all became integral considerations for the ‘poly’ (many) receiving and sending centres. Joseph Handley helps highlight the importance of the concept, asserting that polycentrism meant ‘many centres, from everyone to everywhere’.5

To lessen the hold of some constraining paradigms that once defined those centres, the authors here elected to circumvent binary terms such as Global North and Global South. We intentionally abstain from using polarizing terms like developing/developed worlds, majority/minority worlds, or even Two-Thirds World. We refer to continents and countries by their names to avoid inappropriate clustering and unnecessarily limiting constructs.

Biblical and Historical Models

Mission has been polycentric from the start. Jerusalem was the church’s first mission centre.6 Following persecution, the church scattered across the Roman world as far as Phoenicia, Cyprus, and Antioch, preaching the message to Jews only.7 However, some from Cyprus and Cyrene went to Antioch and preached to Greeks as well and many Gentiles believed.8 Antioch then became the centre for Paul’s missionary journeys and of documented church planting throughout the Roman empire. This Antiochian church launched missionaries to Asia Minor. From there Paul then invited migrant Jewish believers living in Europe to become another mission centre, and so God continued to raise mission initiatives from diverse fields.

In the 20th century newer mission centres emerged in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.9 In Latin America, for example, mission efforts began shortly after the first churches were established there, well preceding the 1910 Edinburgh Conference.10 Timothy Halls observed that Panama 1916 reflected one of many missiologies enacted in Latin America at the time, saying, ‘As Latin America was filling up with the gospel [ . . . ] it found its paths to the rest of the world.‘11 In 1987 Luis Bush invoked the common meaning of Panama 1916 at the first COMIBAM congress, saying, ‘In 1916, Americans [. . . ] declared Latin America to be a mission field, today we gather in São Paulo to declare Latin America to be a missionary force.’12 Panama 1916 defined a new gospel centre and 1987 marked its commitment to grow.

The 2016 WEA-MC Global Consultation in Panama13 highlighted this diversification of mission centres.14 Bertil Ekström, formerly WEA-MC director, referred to the Panama Canal as ‘a sort of a metaphor for an increasingly polycentric world, and for the church as well’. He further noted that as the Holy Spirit sent people into God’s mission, he drew from ‘most of the corners of the world’ and God’s people were sent ‘to all the nations’.15

Recent decades have seen phenomenal changes,16 as missionary work has become a wonderful mosaic of peoples, cultures, flavors, sounds, and much more.17 Fung observes, ‘Today we see churches of all sizes from around the world involved directly in cross cultural ministries (and) partnering with a mission agency is just one of many options.’18 Unlike traditional agencies, many African churches see themselves as centres of mission, bypassing agencies even where they exist. The Assemblies of God-Kenya send missionaries directly to the unreached. This is also happening in smaller churches like the Deliverance Church (Ngong Vet, Kenya), who are sending missionaries to an unreached group abroad. Perbi and Ngugi, working to mobilize the African Church, note, ‘The history of the World Christian movement is the story of the collaboration between local churches and mission agencies (which) God has used . . . to advance the gospel right from the first century to date. These structures enrich each other and accomplish more together.’

There is great conversation and effort to find equally beautiful and adequate ways to collaborate and not compete. This is an ongoing journey. Six areas are worth further examination on this journey, with three highlighting contemporary shifts and three identifying opportunities for polycentric mission.

Contemporary Polycentric Shifts

Methodology

Despite global demographic shifts, deployment from historic sending centres continues.19 The Africa Inland Mission (AIM), for example, keeps a hierarchical structure, but collaboration and cooperation now define its methodology to ‘see a church for every people group in Africa’.20 Previously, the question was ‘How does AIM accomplish its mission?’ Now they ask, ‘How do we (including local partners in the field) accomplish our mission?’ AIM’s African mobilization hubs in Kenya and Tanzania, with a majority being non-AIM staff, reflect this reality. Retaining their objectives, the driver’s seat is occupied by locals and partners.21 Key positions, including regional offices, are now led by Africans.22 This is novel, since AIM remains a Western agency.

Living interculturally is one way that mission agencies formed in the 1800s can fulfill their mandate in new mission contexts.23 AIM leadership affirms that living interculturally ‘creates a culture within an organization that is recognizable and comfortable, so that not just US citizens but also Nigerians feel comfortable, while all are feeling uncomfortable as well.’24

Education

Polycentric mission warrants a devolved, multisectoral approach to educational administration and management. In all educational processes, students, teachers, parents, administrators, and policymakers must be intentionally, proactively, mutually, passionately, and consistently involved. Once-receiving fields that are now sending must raise contextual issues to discover homegrown solutions. Traditional sending institutions can no longer monopolize defining terminology. Many current educational approaches were colonial-era legacies that have undergone little or no review. This has inadvertently affected the quality of education, advanced irrelevance and fragmentation in curricula, and immensely contributed to rising societal inequalities. Gaps created by these inequalities resulted in inefficient educational processes exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Polycentrism offers great potential for the design of educational policies and programmes,25 the improvement of education globally,26 and the creation of unique programme designs for specific contextual needs.27 Acknowledging that the history of education is deeply integrated with the history of missions and missionary work, missional leaders, policymakers, and all stakeholders in the education sector can reclaim lost territory to make an impact for the fulfillment of the Great Commission.

Mental Health

Mental health has a direct correlation with well-being and the ability of individuals and communities to flourish.28 Recent decades saw increased globalization and glocalization as millions traversed the globe for short-term missions and tourism of all kinds, including religious, fitness, education, and entertainment. While these movements enhanced the well-being of some and promoted positive achievements in life or organizational mission, it also left others in poorer mental health due to broken relationships, failed projects, and unmet expectations.29

Polycentric mission can enhance people’s capacity to focus on their strengths and offer knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes globally. The internet increases the capacity to share beyond local contexts. Social media platforms facilitate sharing images, ideas, skills, and all manner of knowledge. While some successfully create thriving businesses, mission agencies, and educational ventures, others succumb to unhealthy consumerism and frustration. These vast opportunities have led to vices such as cyber bullying, cyber insecurity, and internet addiction. Hence, one of the main tools of polycentricism, the internet, has simultaneously contributed to poor mental health among many communities.

Opportunities For Polycentricism

Research

As God wills and gives capacity, polycentric mission will benefit increasingly from research to mobilize the Church’s best-suited representatives to their most-appropriate places of service.

Historically, mission deployment has begun with an analysis of need. At the First Lausanne Congress in 1974, Ralph Winter advocated for the prioritization of unreached people groups. This set the stage for focused deployment based on relative lack of gospel access.30 By the turn of the century, the church had relatively efficient listings of the world’s people groups.31 Refinements of the strategic definitions of ‘need’ then followed. Patrick Johnstone categorized long lists of people groups into a pragmatic two-tier hierarchy of 15 affinity blocs and 251+ people clusters.32 People clusters are now widely recognized as ‘useful for big picture thinking [ . . . ] strategy development and resource allocation’.33 The Joshua Project affirms ‘the people cluster concept can lead to improved efficiency and effectiveness as the missions force works to make disciples of all nations’.34

There is great conversation and effort to find equally beautiful and adequate ways to collaborate and not compete.

In addition to need, analyses of affinity can and shall be a source of wisdom for polycentric deployment. Models like the Cultural Dimensions Theory can help cross-cultural workers recognize interpersonal challenges and lower relational barriers.35 Tools like ‘The World Values Survey’ can give ambassadors for Christ enhanced understanding of their own and others’ values to make relationship-building more thoughtful and authentic.36

These emerging resources promoting cultural appreciation of the ‘other’ also will aid strategic intercession, as research and prayer can be two sides of the same coin. Through informed awareness of the resources of the Global Church, the needs of the world, and the recognition that no one can do everything, everyone can do something. Intelligent and effective prayer for the whole world can happen anywhere and everywhere.

Migration

Migration has historically been a part of mission. Yaw Perbi asserts that ‘Africa’s 500,000 international students (10 percent of the global population) are the African diaspora’s “best-kept secret.” Even if 50% of them are Christians, that’s a 250,000-strong army for the Great Commission!’37 And as Nzathan Moore and Victoria Bfreeze note, ‘the surge in the number of African students in China is remarkable. In less than 15 years, the African student body has grown 26-fold, from just under 2,000 in 2003 to almost 50,000 in 2015.’38 Perbi and Ngugi summarize, ‘Christian students in restricted nations [. . .] can be considered a modern mission force funded by hard-to-access nations that need missionaries.’39

Mission may not be global at all unless funding for mission is a global reality.

Further, economic migration continues to create special access to countries not open to traditional missionaries. Kenneth Ross, for example, associates the economic hardships in Africa with migrant missionaries.40 It remains a responsibility of the church in Africa, Latin America, and Asia to be intentional in training migrant believers so that, as they go abroad they can, as with Priscilla and Aquila, be effective witnesses to the gospel.

Resource Mobilization

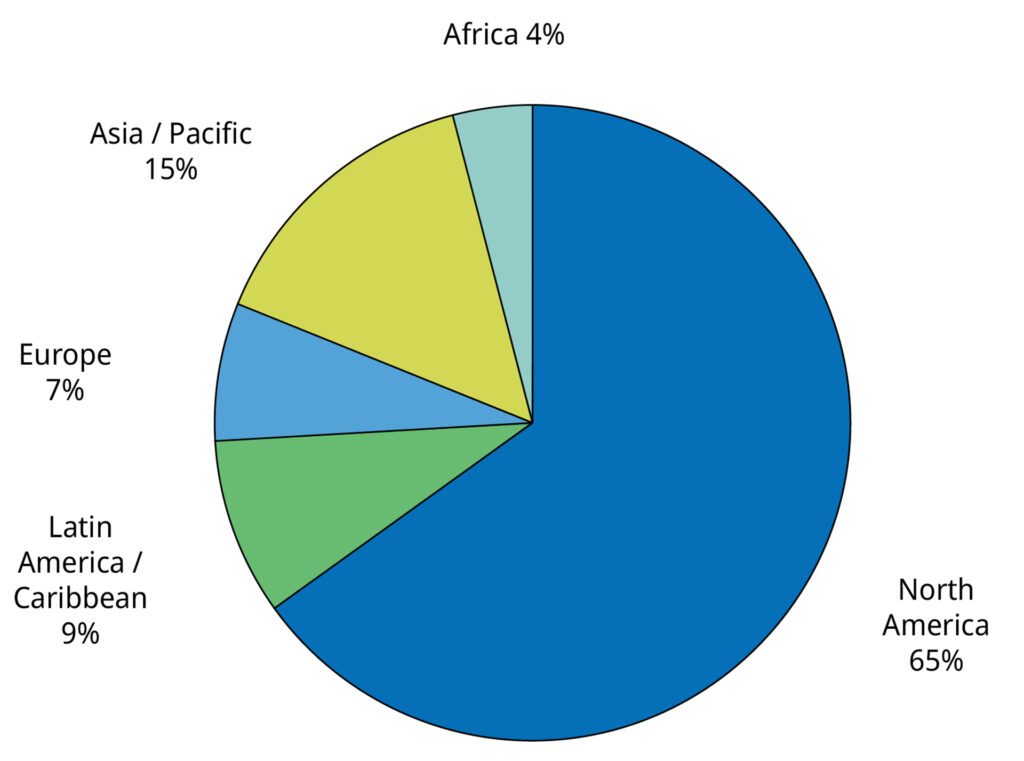

Mission may not be global at all unless funding for mission is a global reality.41 While most evangelical wealth is currently held by believers in North America,42 the simultaneous challenges that face a polycentric church are: (1) how to encourage generosity and accountability in those who hold wealth, (2) how to create healthy channels between those who hold more wealth and those who hold less wealth, and (3) how to create new sources of funding.

Figure 1: The Income of Evangelical Christians 2020

Kirk Franklin and Nelus Niemandt examined data from five consultations convened by the Wycliffe Global Alliance in 2013–2014 on ‘Funding God’s Mission’.43 One goal of this research was to ensure that leadership from the church worldwide could contribute ‘as equal partners’ in order to ‘provide a balanced influence on mission strategy for mission agencies’.44 Through the listening process, 19 ‘Principles for Funding’ were developed.45 These principles are pertinent beyond the Wycliffe Alliance and, indeed, beyond agency and church structures.

With this expanding collaboration, we can anticipate a wellspring of new resources for missions.46 God’s resources are as boundless as his love. He has collectively placed into our hands and our hearts all that we need to fulfill his commission.

Conclusion

The outworking of increased polycentrism is complicated, but the rewards are greater. With biblical roots, historically-adaptable structures, researched support, and excellent training, healthy ambassadors for Christ can and will disperse globally. There are effective ways to identify, equip, and deploy them, and there are resources to support them to obey the call of Christ. The church of Jesus Christ will send the best at his behest.

Endnotes

- Kirk Franklin and Nelus Niemandt, “Polycentrism in the missio Dei,” HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 72, no.1 (2016).

- Ibid.

- Patrick Fung, “Cooperation in a Polycentric World,” 5.

- Allen Yeh, Polycentric Missiology: 21st Century Mission from Everyone to Everywhere (IVP Academic, 2016).

- Joseph Handley and Micaela Braithwaite, “What Is Polycentric Mission Leadership? What the Trinity, Scripture, and Orchestras Can Teach Us About Decision-Making in the Church,” Lausanne Movement, September 20, 2022. https://lausanne.org/about/blog/what-is-polycentric-mission-leadership.

- ‘But you will receive power when the Holy Spirit comes on you; and you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, Judea, Samaria and to the ends of the earth.’ (Acts 1:8)

- Acts 11:19

- Acts 11:20–21

- Though data is limited, the Middle East was another historic, growing, mission centre. We would be so enriched to learn more of the history of mission in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East.

- In 1908 in Brazil, the Brazilian Baptist Convention supported North American and indigenous missionaries in Chile. In 1910 the Brazilian Presbyterian church sent a missionary to Portugal. In 1911 the Brazilian Baptist Convention sent their first missionary to Portugal, followed by a second worker in 1925. In 1928 the Missão Evangélica Caiuá convened as an indigenous agency focused on the tribal peoples of Brazil. In 1948 MEVA, with a similar vision, was established. In 1946 in Peru, AMEN convened, which was established by Pastor Juan Cuevas to reach indigenous groups in Peru, later growing to send missionaries overseas.

- Timothy Halls, from a verbal presentation at the WEA-MC Global Consultation, Panama 2016.

- Ibid.

- The location, Panama, was chosen to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the 1916 conference.

- ‘The Panama conference (1916) originated as a reaction to the Edinburgh World Mission Conference (1910), as mission organizations who worked in Latin America were not invited. The Edinburgh organizers considered Latin America to already be evangelized by the Roman Catholic Church. The Panama organizers disagreed, and as a result, various North American and European mission societies formed the Committee on Cooperation in Latin America (CCLA in 1913) to discuss mission to Latin America. In 1916 it was calculated that 1% of the population of Latin America was Protestant. In 2014 the figure was nearly 20% (Pew Research). The world is changed.’ (from an All Nations Christian College article).

- Bertil Ekström, from a verbal presentation at the WEA-MC Global Consultation, Panama 2016.

- See Patrick Johnstone, The Future of the Global Church, 238–239. Johnstone notes that in 2000 there were just over 200,000 cross-cultural missionaries, most from North America and Asia, followed by Europe, Africa, Latin America, and the Pacific. By 2010 Asia had the majority, with expansion in Korea, India, and China. Africa and Latin America saw much growth in that period as well. This resource provides well-researched data from 1900 to 2010 and estimates for the period from 2010 to 2050. Among other aspects, he points to church growth, population growth, mission, migration, health issues, and economic changes.

- Personal testimony of a missionary who, with his wife and children. experienced this in the late 90s in Central Asia. For seven years, they were part of a multicultural church-planting team, formed by one family from South Korea, one from the UK, one from the US, and one from Latin America. He testified that it is not only possible or doable, but actually of great value and benefit for demonstrating and proclaiming the gospel of Jesus Christ among those who have not yet heard of or received him.

- Ibid p.9

- AIM, with its origins in the US, has operated in East Africa for 135 years (1885–present). Anthony Swanson currently serves as AIM’s East Africa regional executive officer.

- Personal interview with Anthony Swanson by Dr Steven Mbogo, April 2023. Swanson notes that AIM has experienced a drop of about 100 missionaries in the last 10 years, but missionary numbers to East Africa have generally remained constant.

- Ibid.

- AIM’s central region is led by an African from Botswana.

- Catholic missiologist Antony Gittens is among those that advance ‘living interculturally’. Anthony Gittins, Living Mission Interculturally: Faith, Culture, and the Renewal of Praxis.

- Interview with Anthony Swanson.

- The involvement of multiple stakeholders would contribute to diverse beneficial perspectives. For example, education should provide opportunity for choice where ‘students should be offered a diverse range of topic and project options, and the opportunity to suggest their own topics and projects, with the support to make well-informed choices’ The Future of Education and Skills 2030: The Future We Want. OECD, 2018, https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/about/documents/E2030%20Position%20Paper%20(05.04.2018).pdf.

- Ibid. The collaborative decision-making embedded in polycentric processes could have global impact. A multifaceted approach to dealing with unequitable outcomes of education can bridge the rampant issues of access to quality education. For example, education needs to be integrated where “learners should be given opportunities to discover how a topic or concept can link and connect to other topics or concepts within and across disciplines, and with real life outside of school.”

- Ibid. The engagement of local and regional communities in decision making would address specific contextual needs. For example, education should be relevant where “learners should be able to link their learning experiences to the real world and have a sense of purpose in their learning. This requires interdisciplinary and collaborative learning alongside mastery of discipline-based knowledge” (OECD, 7). The engagement of local and regional communities can lead to unique programme designs for specific contextual needs. Education should be relevant where ‘learners should be able to link their learning experiences to the real world and have a sense of purpose in their learning. This requires interdisciplinary and collaborative learning alongside mastery of discipline-based knowledge.’

- Won Ju Hwang and Hyun Hee Jo, “Impact of Mental Health on Wellness in Adult Workers,” Frontiers in Public Health 9, no. 743344 (Dec. 16 2021), doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.743344 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8716594/

- Rosemary Wahu Mbogo. “Biblical Foundations of Short-term Missions (STMs) and Its Implications for Christian Higher Learning.” Universal Journal of Educational Research 7. no. 6 (2019): 1395–1401. 10.13189/ujer.2019.070607

- Ralph Winter (https://lausanne.org/content/lga/2022-11/ralph-winters-and-the-people-group-missiology)

- David Barrett’s World Christian Encyclopedia of 2001 contained the first published, full list of the known ethno-linguistic people groups of the world.

- Patrick Johnstone, “Affinity Blocs and People Clusters,” Mission Frontiers, March 1, 2007.

- https://joshuaproject.net/resources/articles/why_people_clusters

- Ibid.

- Created by anthropologist Geert Hofstede. https://www.hofstede-insights.com/models/national-culture/

- https://www.iffs.se/en/world-values-survey/

- Perbi & Ngugi, Africa to the Rest, 124.

- Nzathan Moore and Victoria Bfreeze. “China has overtaken the US and the UK as Top Destination for Anglophone Students” Quartz Africa, June 30, 2017.

- Perbi & Ngugi, Africa to the Rest, 71.

- ‘A new (or recovered) pattern of missionary activity is emerging in which the poor take the gospel to the rich. Africa is the world’s poorest continent and unsurprisingly the one from which the greatest number of migrants originate. It is also the continent with the most vibrant expansion of Christian faith. Hence many migrants come from the new heartlands of Christianity and bring the flame of faith to the old centres in the north where the fire is burning low.’ Kenneth Ross, “Polycentric Theology, Mission, and Mission Leadership,” Transformation: An International Journal of Holistic Mission Studies 38, no 3 (July 6, 2021): 218.

- 2020 income data from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.ADJ.NNTY.PC.CD. 2020 evangelical projection from data of Operation World 2010 DVD http://www.orperationworld.org/

- Kirk Franklin and Nelus Niemandt, “Funding God’s Mission: Towards a Missiology of Generosity”, Missionalia 43, no. 3 (2015): 390. http://dx.doi.org/10.7832/43-3-98.

- Kirk Franklin, “Funding,” 385. The data was collected over 18 months, involving 145 people from 51 nations.

- Ibid.

- These principles included the awareness that God invites and enables the church worldwide to participate with him in mission; God creatively provides through a diversity of people, means, and resources; sharing resources is an interdependent, relational activity where all are valued and everyone graciously gives and receives; sharing resources must be sensitive and responsive to multiple cultures and contexts; and ‘in the process of giving and receiving, the dignity of all is honored and valued through respectful relationships and friendships’. See ibid, 401-402, for all 19 principles.

- For example, women are likely to become an ever more significant philanthropic force. See Barna Research, The Impact of Women, The State of Generosity Series, Volume 6.