Mental Health

God’s Desire for Shalom

We are always surrounded by needs, but if we are to proclaim the gospel in the manner that Jesus modeled to us, then it makes sense for us to identify the most serious needs in the world today, both the obvious and the hidden ones, and attend to them for the purpose of the Great Commission. One of the greatest challenges facing the church is to address the needs of people everywhere regarding health and wholeness (shalom). When Jesus proclaimed the kingdom of God, he went around the community to minister to the felt needs of the people (Matt 14, 15:29–39; Luke 19; etc.).

This was at the very heart of Jesus’ ministry on earth as shown by his integration of preaching, teaching, and discipling, complemented by his works of healing and deliverance. Jesus practiced care of the whole person—body, soul, and spirit—in the individuals’ social context. He invites his disciples to continue this form of ministry.

One of the greatest challenges facing the church is to address the needs of people everywhere regarding health and wholeness (shalom).

Mental health care is one of the most pressing needs in every continent. The state of our mental health interfaces with many aspects of what makes us human and how we deal with the challenges of daily life. With the increase in environmental, social, political, professional, and spiritual issues, the number of people facing emotional issues has grown globally. These problems naturally impact a person’s spirituality as well as their sense of self and others. So essentially, the mental health field has wide implications in every sphere of society.

In this report, we define mental health as the state and quality of our emotional, mental (psychological), and social wellbeing.1 As such, poor mental health refers to the poor state or quality of one or all areas of our wellbeing. In fact, mental health and mental illness are phrases that bring a lot of stigma and trepidation across nations and the church. Mental health is not the same as mental illness. Chronic and poor mental health can lead to a mental illness. A friendlier term for mental illness is ‘psychological disorder’, which places more value on the human being. The phrase ‘mental health challenges’ in this article is used to describe a broad range of symptoms and conditions that are experienced as a result of acute and chronic emotional and mental strain due to uncontrollable stressors and experiences in our lives. Such challenges can range from common and daily experiences such as relationship conflicts, burnout, loneliness, anxiety, depressive symptoms, or pervasive sadness, to professionally diagnosed disorders which are severe and chronic forms of mental health challenges such as clinical depression and bipolar disorders.

Mental health challenges are human challenges. All humans experience a degree of mental health trouble at some point in life. In some situations, the strain of life and/or diagnosed disorders can lead some to cry for help through the use of poor coping mechanisms including addictive behaviors, self-harm, and sometimes attempts to end the suffering through suicide. Poor mental health does not discriminate by creed, level of spirituality, educational status, skin color, socioeconomic status, or demographic criteria.

Prevalence Worldwide

A mental health meta-analysis of 174 surveys in 63 countries from 1980 to 2013 revealed that globally, about one in five adults experienced a mental health difficulty or disorder over a 12-month period, while 30 percent of all people will suffer from a mental disorder at some point in their adult life.2 A 2022 WHO report on mental health at work3 estimated that globally 12 billion working days are lost every year to depression and anxiety at a cost of USD 1 trillion per year in lost productivity.

Similarly, reports of increasing mental health challenges are evident across all other parts of the Global South, particularly sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America, in all age groups. In a meta-analysis of 36 surveys across 12 African countries where studies of the prevalence of psychological disorders between 1984 and 2020 were conducted, anxiety-related mental health challenges, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and conditions associated with substance use were reported as most prevalent in those countries in comparison to more severe clinical disorders.4

The number of people struggling with their mental health has increased over the past years in every region of the world.

The Pan American Health Organization of 48 countries and all regions in the Americas shows that South America generally has higher proportions of disability due to common mental illness, while Central America has a larger proportion of disability due to bipolar, childhood onset disorders, and epilepsy.5 In addition, the USA and Canada suffer a high toll of disability from schizophrenia and dementia as well as from devastating rates of opioid-use disorder. In another global study (1990-2019) that examined prevalence rates of 12 mental health disorders and indices that capture overall burden of disease, there was a consistent pattern of increased prevalence and global burden of mental health disorders over the decade with varying rates within regions. For example, in Europe, Western Europe reported higher rates of reported disorders compared to other European regions. Also, Australasia reported the highest prevalence rates of mental disorders across the 204 countries and territories examined.6

As reports of mental health conditions continue to rise globally, the causes can be similar across regions, though varying in types when the Global South is compared to the Global North. For example, in the Global South, the increase in reports has been in part due to increased public awareness, while many barriers to mental health care remain, including stigma, limited access, high costs, and insufficient government funding.7 Also, while many developing nations in the past decade have joined initiatives by the World Health Organization via the Mental Health Gap Action Program (mhGAP) to increase education, awareness, advocacy, and care,8 progress toward these goals has still been slow when compared to progress in the Global North.

While the above-mentioned concerns are still present in the Global North (eg among indigenous people groups), it appears that they are not present there to the degree that they are in countries across the Global South. Overall, inequities including health care resources and access, limited education, abuses of power, and financial inequities continue to be the common roots of poor mental health and mental health challenges experienced globally.

The number of people struggling with their mental health has increased over the past years in every region of the world. In the past three years, we’ve seen a unique spike in reported mental health challenges around the globe due to the direct and indirect impact of COVID-19. A more recent meta-analysis of 35 studies in South Asia9 during the COVID-19 pandemic shows a high prevalence of 34 percent for depression and 41 percent for anxiety. If South Asia is taken as representative of Asia, more than 1.5 billion people out of the total Asian population of 4.7 billion have been struggling with depression or anxiety. In Africa, the Middle East, Oceania, and the Americas, anxiety and depression also spiked during the COVID-19 pandemic due to loneliness, unemployment rates, and a prolonged sense of uncertainty.10

In addition to these post-pandemic repercussions, economic hardships, famines, natural disasters, geopolitical conflicts, and civil disorders continue to bring about a greater onslaught of mental health problems in our world, including a higher rate of suicides. Systemic societal disorders in the form of childhood neglect, sexual abuse, or abandonment, also continue to generate more trauma and shame,11 which in turn will manifest in higher prevalence of depression, anxiety, and other emotional problems.

Mental health challenges of all kinds can become chronic without awareness and early intervention. Also, increased stress, increased strain from caregiving, and the overall financial, emotional, relational burden of ill-health will continue to increase. Beyond care of persons with mental health challenges, the prolonged care of persons with physical ailments (including neurological, communicable, and noncommunicable diseases) will also increase the likelihood of mental health challenges.

Current and Future Gaps Regionally

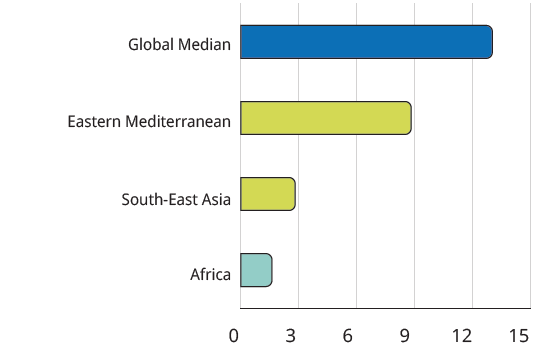

The lack of material and human resources remains an obstacle in many parts of the world. The 2020 WHO Mental Health Atlas states that the number of mental health workers per 100,000 people in South-East Asia is only 2.8, compared with the global median of 13.0.

In addition, 2020 saw only a meager USD 0.10 per capita of government expenditure in these countries on mental health, compared with the global median of USD 7.49.12 Eastern Mediterranean (8.8 per 100,000 people) and Africa (1.6 per 100,000 people) also fell below the global median for mental health workers. In these regions, government expenditure on mental health per capita in 2020 was USD 12.08 and USD 0.46 respectively.

This mismatch between the rising mental health challenges and inadequate personnel and resources to meet them will create huge societal needs everywhere, but particularly in the regions of Asia, Africa, South America, Oceania, and the Mediterranean countries. It also means that attending to these needs can be an easy and effective avenue for Christians to impact the lives of the people in our communities.

The Church Is Not Immune

Unfortunately, the influence of separating our faith from the rest of our lives, as well as an oversimplification of complex situations and phenomena, has permeated our church ideologies and practices, and this in turn has influenced how we perceive and treat mental health challenges.13

Despite the paucity of research on the mental health of pastors, missionaries, and ministry staff, we recognize that many pastors struggle with a variety of mental health challenges and need support for overall wellbeing in order to care for and effectively serve their congregations. A 2020 study by Lifeway Research14 showed that 23 percent of pastors in America acknowledge they have personally struggled with a mental health challenge.

In addition, a 2020 Gallup Survey15 found that 19 percent of churchgoers in America reported that their mental health was less than excellent, meaning that they had some mental health challenges. This exposes a significant need for support, but sadly, the Lifeway study also showed that 49 percent of pastors say they rarely or never speak to their congregation about mental illness or mental health in general.

Overall, the church still experiences a lot of uncertainty when dealing with mental health issues, and the stigma plaguing mental health in society as a whole is still nourished within Christian circles. If the church were equipped with a robust, biblical view of health and what it means to be human, it could be a protagonist in offering vital mental health care in the face of this great global need.

Role of the Church

A biblical understanding of what it means to be human necessitates a wholistic view of health in which mental, physical, and spiritual concerns are bound together. This unity of parts affects every aspect of our lives and our mission in the world. Theological reflection is much needed in this integration. We must take careful stock of our views of church, leadership, discipleship, and the Christian life.

In places where health systems are weak or overloaded, the church can be the first place where people go for help. But if religious stigma, limited understanding, and unwillingness to seek understanding of mental illness close us off to people in need, the opportunity is lost, and we fail to fulfil the Great Commission. We also sacrifice the opportunity to serve them as Jesus would. If we are blind to the suffering of people facing mental health challenges, they will be deaf to our message of hope.

The way the church welcomes people with mental health challenges is also important to the Great Commission. Various forms of abuses of power and of people in the church continue to threaten the credibility of the work of authentic ministers, missionaries, and ministries. We may never know the magnitude of the negative impact such shameful discoveries have on the Great Commission. However, many victims of such abuse experience lifelong psychological disorders which impact their daily livelihood, social relations, and faith in God. While God and his work remain sovereign, abuse of any kind strikes a critical blow to the unity of the body, soul, and spirit. News of these abuses can also produce disillusionment toward God, the church, and the Great Commission.

Within our own walls, poor theology in these areas can take a serious toll on people’s mental health. As humans, we were created by God for communion—to live in interdependent community while recognizing our limitations and possibilities. Church cultures that encourage productivity and activism but deny the importance of rest, spiritual practices, and self-care also neglect Whole Person Care and contribute to the deterioration of mental health instead of promoting integral care. The stigma surrounding mental health for pastors, ministers, missionaries, and staff continues to stand between these workers and the care they and their families critically need. The accompanying lack of such resources and support will limit their own capacity to support congregants who are in need.

Challenges and Opportunities for Great Commission Efforts

As of 2023, the world population is 8 billion, suggesting that about 1.6 billion people are struggling with mental health challenges. The immense need for mental health care offers us ripe fields and an effective avenue to serve people in the community as we present the good news. To meet this need, we must attend to three main areas of growth in our churches.

- Mental Health Literacy and Capacity: Even if a church recognizes caring for mental health as within the scope of our Commission, too often it is ill-prepared to respond. Despite the enormous need for emotional and psychological healing, too few Christian workers are equipped with the knowledge and skills needed for such work. We must equip ourselves with basic Christian counseling knowledge and skills and invest in continuing education to keep abreast with people’s needs. With greater mental health literacy, we will know more about our human nature in the way we think, feel, and behave. This will benefit us both in our own mental health self-care and also in ministering to others. Several practical steps can aid greatly in this effort:

- Schedule an annual mental health awareness week in our churches.

- Offer regular short courses on mental health.

- Motivate members to learn more on mental health through free online Christian teaching.16

- Embrace a multidisciplinary approach in both physical and mental health care, as we already do in our approach to spiritual care and formation.

- Mental Health Services: We must thoughtfully incorporate new ministries within our churches to address the prevention of and care for mental health concerns. Below are practical examples of how churches can offer mental health services in their communities:

- Set up recovery/rehabilitation programs that support people in need rather than shun them.

- Carry out one-to-one counseling and ministry to help people with emotional and mental health challenges both in church settings and in the community. With this, we must understand when to provide referrals to appropriate mental health professionals, like we already do with physical medical conditions.

- Offer support groups focused on grief, effective marital relations, singleness, conflicts, divorce, addictions, parenting, etc.

- Conduct free community talks on mental health topics and follow up with those with specific needs.

- Offer debriefing, trauma, and grief intervention services in disaster relief and recovery outreaches.

- Increase and/or partner with medical care service providers to provide early childhood intervention and other community resources, as this will reduce stress (and eventual mental health conditions) and the burden of disease.

- Church Culture Renewal: Without a robust, holistic understanding of what a person is and needs—ie Christian anthropology—education and resources will be of limited use. We may even sabotage our own efforts through church cultures that encourage productivity and activism while denying the importance of rest, spiritual practices, and self-care. A corrective to this includes:

- Reflecting on how Scripture interacts with our emotions and how these riches can be nurtured by the community of faith in its reading, teaching, worship, conversations, and relationships to strengthen people emotionally.

- Embracing mental health wellness as a lifestyle habit among Christians worldwide, promoting openness and honesty of our needs.

- Increasing opportunities for mentoring and accountability for ministers outside of the communities they serve. This provides ministers spaces in which they can step out of their care-giving roles in order to receive the care and connection they need. This added accountability can also reduce the likelihood for abuse and abusive behaviors.

- Honoring the testimonies and particular wisdom of those who minister out of their own brokenness. While we aim for mental wellness, we also recognize that in our fallen condition, not everyone will become well or fully recover. The peculiar grace such people experience as they pursue Christ in their pain often makes them uniquely suited to carry out the Great Commission in spaces of brokenness.

Hope for Our Great Commission Efforts

Despite the various global challenges in the field of mental health, there are many things to be hopeful about in the next 30 years, including the following:

- An abundance of freely-accessible resources are now available online for equipping Christians in mental health literacy as an additional ministry skill for world evangelism.

- Many Christians are awakening to the reality that theology and psychology are not necessarily opposing fields. Many psychological views are rooted in the Bible. When firmly anchored in biblical truth, the insights of psychological study can enhance our evangelism and discipleship across the world.

- Christians are investing in the training of many Christian mental health professionals globally. This will continue to enhance holistic and culturally competent mental health care.

- God’s word for whole health is true even in the midst of the current mental health crisis. Our mental health matters to God, so he will grant us wisdom to grow and support one another.

Recommended Resources

- Cook, Christopher C.H., Isabelle Hamley (eds). The Bible and Mental Health: Towards a Biblical Theology of Mental Health (London: SCM Press, 2020).

- McMinn, R. Mark. Psychology, Theology, and Spirituality in Christian Counseling (Wheaton: Tyndale House Publishers, 1996).

- McMinn, R. Mark, D. Clark Campbell. Integrative Psychotherapy: Toward a Comprehensive Christian Approach (Downers Grove: IVP Academic Press, 2007).

- Ng, Edmund. Discovering God’s Word Psychologically: Eastern and Western Perspectives (KL: GGP Publishing, 2018).

- Swinton, John. Finding Jesus in the Storm: The Spiritual Lives of Christians with Mental Health Challenges (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing, 2020).

- World Health Organization. Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2030 (Geneva: WHO, 2021).

Endnotes

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “About Mental Health.” https://www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/learn/index.htm.

- Steel, Zachary, Claire Marnane, Changiz Iranpour, Tien Chey, John W. Jackson, Vikram Patel, and Derrick Silove. “The Global Prevalence of Common Mental Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis 1980-2013.” International Journal of Epidemiology 43, no. 2 (2014): 476-93. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu038.

- World Health Organization. “Mental Health at Work.” September 28, 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-at-work.

- Greene, M C., Tenzen Yangchen, Thomas Lehner, Patrick F. Sullivan, Carlos N. Pato, Andrew McIntosh, James Walters et al. “The Epidemiology of Psychiatric Disorders in Africa: A Scoping Review.” The Lancet Psychiatry 8, no. 8 (2021): 717-731. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00009-2.

- Pan American Health Organization. The Burden of Mental Disorders in the Region of the Americas, 2018 (Washington, D.C.: PAHO; 2018).

- GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. “Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.” The Lancet Psychiatry 9, no. 2 (2022): 137-150.

- World Health Organization. “Barriers to Mental Health Care in Africa, 2022.” October 12, 2022. https://www.afro.who.int/news/barriers-mental-health-care-africa.

- World Health Organization. mhGAP: Mental Health Gap Action Program: Scaling up care for mental, neurological and substance use disorders (Geneva: WHO Press, 2008).

- Hossain, Md Mahbub, Mariya Rahman , Nusrat Fahmida Trisha, Samia Tasnim, Tasmiah Nuzhath , Nishat Tasnim Hasan, Heather Clark, Arindam Das, E Lisako J McKyer, Helal Uddin Ahmed, Ping Ma. “Prevalence of anxiety and depression in South Asia during COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Heliyon 7, no. 4 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06677.

- Dragioti, Elena, Han Li, George Tsitsas, Keum Hwa Lee, Jiwoo Choi, Jiwon Kim, Young Jo Choi et al. “A large‐scale meta‐analytic atlas of mental health problems prevalence during the COVID‐19 early pandemic.” Journal of Medical Virology 94, no. 5 (2022): 1935-1949. DOI: 10.1002/jmv.27549.

- Edmund Ng. Shame-Informed Counseling and Psychotherapy, Eastern and Western Perspectives (New York: Routledge, 2021), 77-82.

- World Health Organization. Mental Health Atlas 2020. 52.

- Lausanne Movement. “Health for All Nations.” https://lausanne.org/networks/health-for-all-nations.

- Aaron Earls. “Mental Health Declines Among Americans, Except Weekly Churchgoers.” December 11, 2020. https://research.lifeway.com/2020/12/11/mental-health-declines-among-americans-except-weekly-churchgoers/.

- Megan Brenan. “Americans’ Mental Health Ratings Sink to New Low.” December 7, 2020. https://news.gallup.com/poll/327311/americans-mental-health-ratings-sink-new-low.aspx.

- One such resource is Safe Space Community, https://www.safespacecom.org.