Creation Care

Sometimes it takes a major shift in human society for God’s church to rediscover biblical truths that have been overlooked. It was only in the age of exploration and empire that Western Christians recovered an understanding of world missions. Trade and conquest were deeply problematic and often sub-Christian, but they opened the eyes of Christians in Europe and North America to the millions of people in other lands who needed Jesus.

Today, our context includes a world of exploding human consumption, pollution, and waste. The planetary boundaries within which God designed life to flourish are under threat, leading to existential threats to human society and life on earth. This article will briefly outline some of these threats to sustainable living, examine the profound biblical questions they pose, and look at some case studies of Christian responses around the world.

The Context of Creation’s Groaning

Human-induced climate change dominates media coverage and governmental initiatives concerning environmental issues. For example, the Sixth Assessment Report of the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) states that, ‘human activities, principally through emissions of greenhouse gases, have unequivocally caused global warming.’1 In plain, yet chilling, language the report demands, ‘deep, rapid and sustained global greenhouse gas emissions reduction’ to avoid ‘abrupt and/or irreversible changes’2 to earth’s ability to sustain human and other life. As climate scientist and evangelical Christian professor Katharine Hayhoe says, ‘Climate change has already caused widespread and substantial losses to almost every aspect of human life on this planet, and the impacts on future generations depend on the choices we make NOW.’3 For Christians, this is an urgent issue of justice and also begs the question, ‘What is the good news we proclaim whilst we are destroying God’s good creation?’

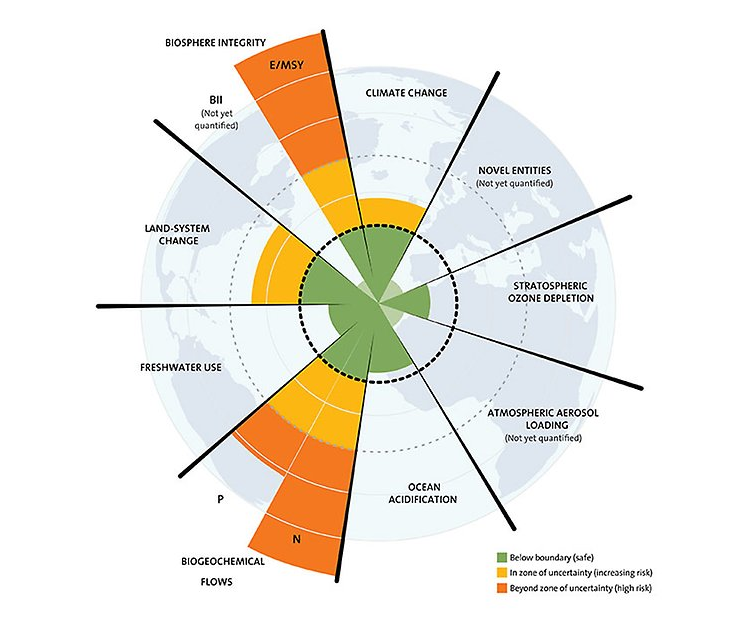

Sadly, however, climate change is only one of multiple environmental challenges we face in the twenty-first century. Researchers increasingly use the concept of ‘planetary boundaries’4,5 to describe nine areas of human impact upon natural systems.6

Figure 1. The nine planetary boundaries

The boundaries use a traffic light system to indicate whether current human impact is ‘green’ (a safe operating area for humanity), ‘amber’ (zone of uncertainty and risk), or ‘red’ (high risk to human thriving). It can be seen that ‘Climate change’ is currently in the amber or warning zone, whereas ‘Biochemical flows’ and ‘Biosphere integrity’ are both deeply into the red danger zone. In brief, ‘Biochemical flows’ refer to the use of nitrogen and phosphorus in agricultural fertilizers and their impact on soil and water quality. ‘Biosphere integrity’ concerns the loss of species and habitats worldwide (biodiversity loss). The support systems on which all life depends including oxygen from plants, pollination from insects, healthy food, clean water and a stable climate are rapidly deteriorating due to humanity’s accelerating impact. To illustrate this, it is estimated that of all mammals on earth 96 percent are livestock and humans, and only 4 percent are remaining wild mammals.7,8 This poses serious theological and missiological questions regarding the future of human life, human population and consumption, and God’s purposes in and for creation.

The Content of the Great Commission

The environmental threats we face this century matter because belief in God as Creator is a fundamental tenet of Christian faith. They force us to ask not only ‘What is the state of the Great Commission?’, but ‘What is the Great Commission?’ To put it simply, is Jesus’s command to make disciples of all nations simply a call to rescue people from a dying world? In that case, the state of the planet is either irrelevant or simply an incentive to evangelize faster. Alternatively, does the Great Commission include creation care itself as part of the proclamation of the Gospel and essential to ‘making disciples’?

The Lausanne Movement gave a clear answer to this question at the Third Lausanne Congress in 2010. The Cape Town Commitment asserts that, ‘we cannot separate our relationship to Christ from how we act in relation to the earth. For to proclaim the gospel that says “Jesus is Lord” is to proclaim the gospel that includes the earth, since Christ’s Lordship is over all creation. Creation care is thus a gospel issue within the Lordship of Christ.’9 The Great Commission has always been about making disciples, rather than converts, and disciples are those who allow Jesus to be Lord in every dimension of their lives. The Cape Town Commitment is clear that the gospel, the good news of Jesus Christ, ‘includes the earth’ which was created, is sustained and will be redeemed by and through Christ. Therefore, to fail to care for creation is to fail to allow Jesus to be Lord.

The Cape Town Commitment asserts that, ‘we cannot separate our relationship to Christ from how we act in relation to the earth.

Moreover, The Cape Town Commitment goes further in giving a concise definition of biblical mission including creation care: ‘Integral mission means discerning, proclaiming, and living out the biblical truth that the gospel is God’s good news, through the cross and resurrection of Jesus Christ, for individual persons, and for society, and for creation. All three are broken and suffering because of sin; all three are included in the redeeming love and mission of God; all three must be part of the comprehensive mission of God’s people.’10 These three dimensions of mission identified by the Lausanne Movement—the spiritual, the social, and the creational—provide a helpful framework by which to measure the effectiveness of missions and therefore, ‘the State of the Great Commission’. If our task is to make disciples of Jesus, who is Lord of all Creation (Ephesians 1:20-23; Colossians 1:15-20), and who teaches us to pray for God’s kingdom ‘on earth as it is in heaven’ (Matthew 6:10), then fulfilling the Great Commission includes justice for all people and the flourishing of all creation. We need adequate metrics to measure not only people groups reached, languages the Bible is translated into, and churches planted, but also to measure social and ecological impacts of our missional activity.

Of course, the danger of including the social and creational dimensions of mission is losing our focus on evangelism. This was the mistake of the ‘social gospel’ movement of the early twentieth century. It is still present amongst those who focus only on climate and poverty without preaching the saving message of Jesus Christ. Yet, the mistake we evangelicals have often made is to react so strongly against this danger that we ignore the biblical mandate to care for the poor and for creation. In doing so, we reject the full Lordship of Christ, because to say ‘Jesus is Lord’ includes his Lordship over society and creation. As has been argued elsewhere,11 the key to avoiding losing our focus is to ensure that all our missional activity, ‘spiritual’, social and creational, is focused on Jesus Christ, rooted in Scripture, and fully integrated in demonstrating the whole gospel for the whole world.

The following case studies illustrate ways in which Christians in different global contexts are integrating creation care within their fulfillment of the Great Commission.

Missional Case Study: Indigenous Perspectives on Mission and Creation

In indigenous understanding and experiences, talking about the Great Commission and the missionary task of the church means thinking about the importance of all relationships, including the sense of community in, with, and from the environments where we live. Everything is connected in this awareness of belonging within community territory. The sense of belonging that we have towards the land offers a holistic dimension and perspective regarding salvation and living out the gospel. Therefore, not including this perspective in our experience of faith and life is to reduce the scope of the gospel, which includes all creation in Christ’s salvific work. These relationships include the relationship between all creation and its Creator, which many indigenous people understand to be a great mystery. Our way of living with mystery, in the midst of life’s ambiguities, keeps us humble, helps us recognize that we are from the earth, we are creation’s younger brothers and sisters, and creation has a lot to teach us about how to walk well on the earth so that we can all live well.

From their worldviews, indigenous peoples propose a life of reciprocity and complementarity—life perspectives that allow us to fertilize our faith experience and missiological and theological work. Also, the way we live in and interpret the world (including theology and mission) and our relationships in the community of creation is through our territories. Indigenous perspectives can help us recover the deeply biblical connections between people, land and faith which we see in Scripture. Indigenous peoples also offer a way for the Euro-centric church to return to a theology and mission based on particular relationships to a particular space, which helps us see how our theology does have an impact on the earth.

Missional Case Study: Development vs. Environment

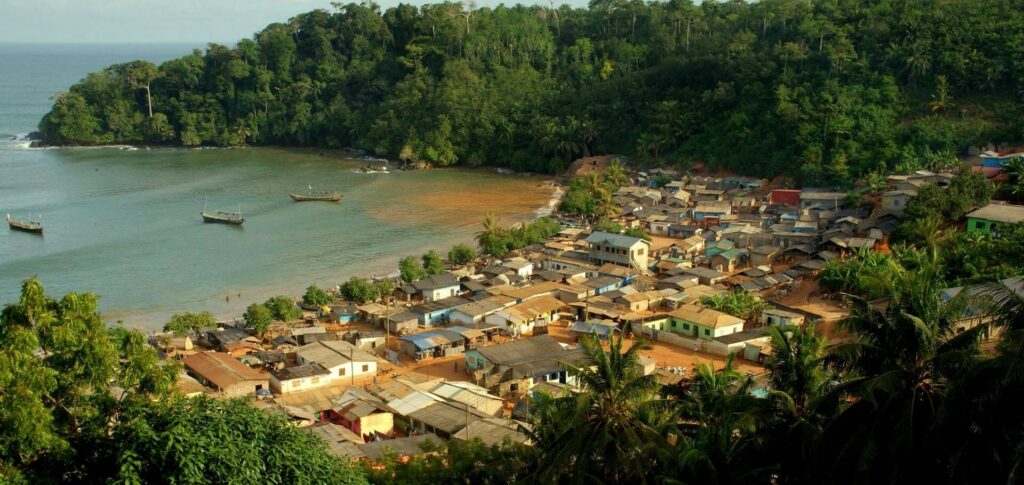

The Atewa Forest lies 90 kilometers north of Ghana’s capital, Accra. It contains unique and rich biodiversity, including 1100 plant species, 77 percent of Ghana’s butterflies and 30 percent of Ghana’s bird species, and is recognised as a Globally Significant Biodiversity Area (GSBA). It also holds the headwaters of three river systems providing water for millions of people and for industry. In addition, it has great cultural, historical, and spiritual significance to indigenous communities of the Akyem Abuakwa Traditional Kingdom.

As an emerging economy, Ghana needs development finance. In 2019, the Ghanaian government entered into a USD $2 billion loan agreement with China to mine Atewa for bauxite (for aluminum), destroying much of the forest, in exchange for rail and road building. This created a challenge for A Rocha Ghana, a Christian organization working to protect biodiversity and build sustainable livelihoods. How should we respond to actions that will have devastating consequences on critical ecosystems and impact negatively on communities’ livelihoods? Does keeping quiet taint our confession of faith as Christians working in conservation? Should quick profits, little of which will benefit local communities, triumph over long-term green development?

A Rocha Ghana listened to local people, who had not been consulted, conducted careful scientific research to gain evidence, and began a ‘David vs. Goliath’ campaign against the proposed destruction of Atewa Forest. Through public campaigning, political advocacy, international pressure, and finally legal action against the government of Ghana, a small Christian organization has stood up for people and planet against powerful political and economic forces, drawn global attention to Atewa, and has, so far, delayed the implementation of the forest’s destruction. Seth Appiah-Kubi, Director of A Rocha Ghana states, ‘This is a practical demonstration of our faith in the God of creation and our role as stewards of God’s earth.’

Missional Case Study: Mission Agencies and Creation Care

As creation care gains traction in both urgency and importance, mission agencies are actively incorporating care of creation in their missiology and practice. OMF International, for example, has long been exploring how creation care is part of integral mission, and created their own statement on the theological basis for creation care in 2014. For those in OMF this means that, ‘regardless of our ministries and contexts, we can care for creation not only in what we do, but as who we are.’12

Creation care is, therefore, not just a pressing context for mission. Creation care is also integral to the content of the Great Commission.

Expressions of creation care are different across OMF because of each person’s unique ministries and contexts. In Mongolia, some are embracing the opportunity to respond to the challenge of air pollution and its impact on human health and livelihood. In another part of Asia, some are involved in research on water quality in seagrass and mangrove regions. This research has been a gateway for local communities to experience the beauty of God’s creation within their surroundings. In the UK, others are integrating creation care not only in practical ways—such as reducing energy consumption in buildings—but also in how they mobilize people to engage in God’s mission. All in all, OMF continues to strive towards living out creation care as a posture, rather than merely as a program.

OMF is only one of several mission agencies with a keen desire to integrate creation care. As such, several of these agencies, including OMF, are now part of the recently formed Mission Agencies & Creation Care (MACC) Network under the umbrella of the Lausanne/WEA Creation Care Network (LWCCN). While each agency is at a different point in their creation care journey, MACC is a valuable space to explore specific topics, to share resources and strategies, and to pray for one another.

Conclusion

The call to respond practically and urgently to our multifaceted ecological crisis is not simply topical. It is deeply biblical, rooted in God as Creator, Jesus as Lord and Saviour of creation, and the Holy Spirit who sustains and renews the earth. Creation care is, therefore, not just a pressing context for mission. Creation care is also integral to the content of the Great Commission. We are called to make disciples who live out the truth that Jesus is Lord of all creation. Without this, we risk ineffective evangelism in failing to address today’s deepest questions. Without this, we risk Business as Mission simply baptizing a system that destroys the planet. Without this, we fail to witness that Jesus is Lord of all. But, as Christians around the world are discovering in exciting new ways, when Christians take the earth seriously, people take the gospel seriously. In Romans 8:19, we read ‘Creation is waiting for the children of God to be revealed.’ As those adopted as God’s children, the global church, creation is waiting for us! Are we ready to respond to our Great Commission to share God’s good news for all creation?

Endnotes

- “AR6 Synthesis Report: Headline Statements, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change” (section A.1), accessed May 31, 2023, https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/resources/spm-headline-statements.

- ibid (section B.3), Accessed May 31, 2023.

- Katharine Hayhoe, March 20, 2023, https://twitter.com/KHayhoe/status/1637875896433385481?lang=en.

- Johan Rockström et al., “A Safe Operating Space for Humanity”, Nature 461, no. 7263 (2009): 472-75.

- Will Steffen et al., “Planetary Boundaries: Guiding Human Development on a Changing Planet,” Science 347, no. 6223 (2015): 736-46.

- “The Nine Planetary Boundaries,” Stockholm Resilience Centre, University of Stockholm, Accessed May 31, 2023, https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/planetary-boundaries/the-nine-planetary-boundaries.html.

- Yinon M. Bar-On, Rob Phillips, Ron Milo, “The Biomass Distribution on Earth”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, (2018), Accessed June 1, 2023 https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1711842115

- 36% humans, 60% livestock, 4% wild mammals, accessed 1 June, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/may/21/human-race-just-001-of-all-life-but-has-destroyed-over-80-of-wild-mammals-study.

- “The Cape Town Commitment”, Accessed June 2, 2023,https://lausanne.org/content/ctc/ctcommitment#p1-7

- ibid.

- Dave Bookless, “A Missional Theology of Creation Care”, Evangelical Missions Quarterly, Missio Nexus 59(2) (2023): 13-1812.Jasmine Kwong, “Posture Over Program: OMF’s Journey into Creation Care”, Evangelical Missions Quarterly, Missio Nexus 59(2) (2023): 24-28.