Ministry Data in a Digital Age

Digital Data, Digital World

In 2006, Clive Humbly, a British mathematician and data science entrepreneur, coined the phrase ‘data is the new oil’, heralding the prominence of data to the fledgling digital age. Data Science was still in its initial stages of development in the West, and the church at-large often had a somewhat stilted relationship with missional information. Average Western church-goers simply did not preternaturally have much awareness to acquire or question the existence of any such resource, let alone their fellow congregants from among the Global South. Notably, many in the Majority World often have a very different relationship with data as an industry or science.

Notably, many in the Majority World often have a very different relationship with data as an industry or science.

Historically, ministry data reflected information primarily obtained for Western missiological audiences, in the sense that it often spoke to issues such as evangelical presence, the concerns of gospel access and Scripture’s availability, or tracking denominations at a national level. Advocates utilized the available findings to inform Western missional strategy. This information was often curated with a specific project, focus, or strategy in mind, but much of the information was retained and protected by those that created and published it. Any additional significance required an external awareness that such resources were available; how global data was curated and produced might often not be known outside of the originating ministry. Conversely, the data might have had unperceived value to audiences that the data was not originally intended for.

As the appetite for globally comprehensive, consistent, and accessible data grew larger, publicly available mission datasets rose to prominence. For example, resources like Operation World1 and the World Christian Encyclopedia2 produced comprehensive, printed (and at one time disc-supported) volumes that provided prayer-catalytic content, which they continue to update and release on a periodic basis. However, the very existence and viability of some of those few providing ministry data was often dependent on monetizing the printed material or product they provided. Lacking that, some raised personal support to fund research, some obtained sponsorship for individual projects, or at times the work was personally fundraised. Others, like Global Mapping International (www.gmi.org), were ultimately unable to continue serving as researchers and key technical service providers. These examples of work have warranted their earned esteem while unintentionally portraying a predilection for English speaking, Western-minded missional leaders, sometimes at the expense of global participation.

Then, in March 2020, the world shifted, and with it, the significance of the digital age. The societal repercussions of COVID were forcing new normals for movement, interaction, and engagement.3 It changed what types of data people trusted and how they interacted with that data4. In some cases, COVID even changed what people believed. In the weeks and months after March 15, 2020, the digital world became not only the primary medium of operation for information exchange, but was now affecting nearly every aspect of our lives. Church and mission functions that traditionally would have been conducted solely in person were on hold or forced to adapt. COVID affected where and how missionaries were able to be sent, as well as who was able or willing to participate in ‘church’. 5 No one knew how long the interruption would last or if we would ever return to ‘normal’.

COVID altered our relationship with ministry data in a variety of ways. There was erosion of public trust in global data authority, in part due to how pandemic data coverage was politicized.4 This encouraged a reexamination of data validity and collection methodology across the board.6,7 COVID allowed for new modes and patterns of communication that brought previously distant relational networks into tighter and more transparent orbits. Longstanding questions or concerns over sanctioned missional data from both Western and Majority World leaders now became inexcusably actionable opportunities. These discussions underscored the fact that the world was able to change much faster than existing data systems and paradigms were able to reflect those changes. Indeed, were true veracity and up-to-the-minute time relevance even obtainable data ideals? Once familiar ministry data was questioned anew. Could data become more effective for informing ministry strategy in this new, shifting environment or would traditional datasets be relegated to increasing irrelevance as the world continued changing?

Ministry data, and data as ministry, will be more critical than ever before as the digital world rewrites immediate insight, access, and relational connectivity as the new normal.

These changes amplify the urgency for the global church to reevaluate the way it supports and interacts with data as a ministry. Data integrates research, information, and the technology that emerging Christian forces use for communication, education, deployment, and application of strategic ministry direction. Ministry data, and data as ministry, will be more critical than ever before as the digital world rewrites immediate insight, access, and relational connectivity as the new normal.

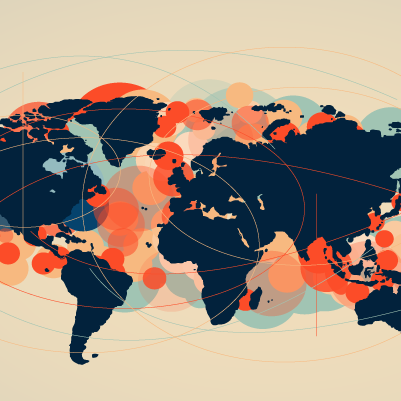

Transformation of Ministry Data

The quantifiable amount of data that global ministries and their teams are now able to cultivate is unprecedented, encompassing anything and everything from digital gospel engagement to oral communicator surveys to the GPS coordinates of house churches. And it will continue to expand as new ministry needs are revealed and more workers come alongside to innovate. Global data accessibility is transforming how data is collected, interpreted and strategically applied. As the body of Christ continually expands and diversifies, the goal for global data is stewardship, ownership, and utilization by a body that better reflects today’s church.

In addition, an entirely new field of study and expertise around data science, data analysis, and data engineering has burgeoned and matured within just the last decade. Recent advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning further propel the field of data forward at ever increasing rates towards presently unimaginable frontiers. Indeed, at the time this paper is read, we should anticipate whether our current perspectives on global ministry data will still be relevant.

The global church is at a pivotal junction in respect to the modern data revolution. It stands on the inherited foundations of a core group of ministry datasets generated by a select group of dedicated workers (almost none of whom were salaried), and a future where the opportunities and applications for global ministry data and access to the gifts of a wide pool of data professionals and practitioners are seemingly endless. In an emerging world where everything is computable, up-to-the-minute data relevance is absolutely mandatory for informed ministry strategy. The question is not one of data relevance or collection, but of data integration and interpretation. The church must be adequately staffed and equipped to navigate this new era.

The core competencies of data literacy, data collection, and specifically, data interpretation become undeniably essential ministry functions of the global church. The Community of Mission Information Workers (CMIW)8 calls the body of Christ’s attention to the need for engaging and equipping the global church in the ministry of data, as an essential element to facilitate Great Commission efforts in the coming decades. The ministry of data must be integrated into the fabric of today’s maturing global church.

Global Data Consolidation, Local Data Proliferation

There are certain developments involving ministry data that justify special attention.

Consolidation of regional and global ministry data into key resources

Sources such as the Joshua Project9, the Global Status of Evangelical Christianity (GSEC) as reported by the International Missions Board (IMB) for the Southern Baptists,10 Cooperación Misionera Iberoamericana (COMIBAM),11 and The Movement for African National Initiatives (MANI)12 are often utilized for church planting and discipleship strategies. Other works and sources, such as the Center for the Study of Global Christianity,13 Ethnologue,14 and Progress.Bible15 are more academic in their focus and research. We recognize that not all of these are Western in source nor global in scope; this move toward inclusivity is a welcomed development. These sources are the backbone to many well-reasoned and funded ministry strategies, sometimes to the extent that they gain preeminence over the knowledge and realities of the people they strive to represent. The challenge for these globally reputed datasets will be the strain of maintaining accurate representation while their influence and authority both expands and consolidates.

Rapid expansion of what constitutes ministry data itself

This includes what is measurable and worth measuring, how to identify it, and who can access it or effect it. Consequently, there is an increased preference for firsthand research and its data sources. Opportunities for crowdsourced data16 are getting noticed and niche focuses illustrate how data often might need to be specific to a ministry’s needs. Projects once considered under-prioritized, difficult to fund, or impractical to support by traditional avenues may now be captured through technical innovations as simple and accessible as GPS tools available via smartphones.17

Both developments—the move towards a consolidation of global data and the proliferation of local data opportunities—are meeting pressing needs and may appear to be the next step in the evolution of data and information. However, they also have the potential to become unnecessarily at odds with each other. But this does not necessarily need to be the case as both have strategic value if fostered interdependently.

Value and challenge of global data

Global datasets have great value in building consensus, providing a comprehensive overview, and helping inform high-level strategy and resource allocation. At the same time, data sources are far from infallible, which may be counterintuitive to some end users. Christian mission strategists are dependent on information for perspective, strategic decision-making, deployment, and even project funding, regardless of those datasets being imperfect or unavailable in ‘real-time’. Of course, providing perfect data is much easier said than done.

Global data is hard to collect, and the organizations and networks that help collect it are vastly under-staffed, under-funded, and under-resourced. It requires an immense amount of contribution, curation, and context. What might not be readily understood by those that use mission information is that each individual piece of mission information has the opportunity to be curated and adjusted to fit within the context of the whole. By their very nature, global datasets require agreement of terminology and metrics, which do not always currently reflect the unique nuances of each community or situation. This is not inherently misleading, as statistical details, populations, and demographic changes occur constantly and such elements need to be reconciled. Yet, in actuality, whoever owns and curates the data owns and informs the perspective it reflects. This can result in anything from inadvertent misrepresentation to outright omission or oversight. This not only creates opportunity for misaligned strategy, but can perpetuate unease between local communities and the data authorities that purport to represent them. It must be said that any adverse effects of consolidated global data were unforeseen and unintended.

Occasionally, funding models require paywalls, and sensitivity becomes a large enough obstacle that even basic public accessibility to ministry data (especially to the Majority World church) becomes a major obstacle. How can the utility and relevance of global data be trusted when local communities face barriers that affect their ability to contribute to or even access global datasets?

Value and challenge of local data

Conversely, the value of local data or particular data lies in its proximity to the actual source of truth, not just geographically or contextually, but temporally as well. A person currently living in a Romani clan in Eastern Europe, a village in West Africa, a jati in India, or a particular generation in China, all have different priorities for how they perceive their own self-representation. These may change more rapidly than global datasets are currently able to accommodate. Particular (local) data emphasizes not only accuracy and nuance of depiction and identification, but also local ownership. In this way, data is not only valued, interpreted, and communicated at a local level, but owned at a local level; external validation becomes secondary. Data is not extracted from communities, but owned and managed by them. This can reflect anything from terminology, metrics used, collection methodology, distribution rights, and strategic application. The tradeoff here is that global aggregation and a seat at the global data table is often the cost of local ownership and self-identification.

Contrary to global data, local data faces the intentional limitation of its scope. The lack of standardized terminology, metrics, and collection methodology may make global aggregation difficult until data normalization and transformation occurs. Local data and particular data become difficult to integrate, face a barrier of low interoperability, and multiply the potential barriers of access and validation. Ironically, inundation of multiple sources of data can unintentionally subvert the clarity of ministry strategy by creating discord and disunity if there is confliction. It should be stated though that confliction and deviation are a normal part of data science. However, by multiplying the voices, platforms, applications, and connections between disparate datasets without careful intentionality, one runs the risk of collapsing the integrity or utility of the entire platform of ministry information. This could result in strategic chaos, which would be catastrophic for global missions strategy.

Local data will also exacerbate the issue of security and sensitivity. Granular data can just as effectively be used for ministry strategy as it can be used against ministries. There are concerns that increased data accessibility may result in undue persecution or a limitation (or even severance) of ministry opportunities. Data ownership, stewardship, and access are very legitimate concerns, and there may very well be situations where local or particular data is best kept far from the eyes of global access. Finding the right balance between visibility and sensitivity has been and will increasingly continue to be a point of tension. Perhaps there is an immediate future where data systems can accommodate the needs and challenges of both global data systems and local data knowledge. We, as a missions information community, feel that is the path forward.

Data as a Ministry of the Global Church

The tension between the merits of global and local data will be an essential topic to tackle and diffuse as the church grapples with the implications of ministry data in a digital age. Often, global data and local data are inherently viewed as at odds with one another, especially when the church is forced to choose between two competing values or two competing data systems in pursuit of a singular source of truth. But as ministry data increasingly serves more than one purpose or perspective, the balance between multiple or conflicting datasets and data systems will need to be something the church is able to come to terms with. Might new data systems and approaches be discovered that allow these discrepancies? We hope so.

Undervaluing and underfunding data as a ministry

The false dichotomy between global and local data is most primarily fueled by a long-perpetuated poverty mentality with regards to funding data as a ministry and building capacity for its collection, analysis, and interpretation. If the global church does not have the value, capacity, or desire to fund the stewardship of missions information work, then ministry data is reduced to its bare minimum—a singular list written from a singular, often unadaptable perspective of a world that is becoming increasingly complex. This is to the global church’s own detriment.

Undervaluing and underfunding data as a ministry severely hampers the opportunities we have as members of the global church to enhance Great Commission vision and strategy. Data can and should serve the church in a multifaceted array of ways. Data can act as a global repository or index, or it can inform nuanced strategy at a local level for a certain issue, paradigm, or cause, championed by a local contingent. It can serve as a platform for inclusivity, crowdsourcing and collaboration, or it can serve to demonstrate authority and credibility. It can identify trends. It can predict the future. It can help engender representation. Multiple conflicting datasets can actually help hone accuracy by offering different perspectives and inviting increased collaboration.

Welcoming and supporting data as a ministry

The biggest enemy to the usefulness of robust ministry data is the lack of value and investment in data literacy by the global church. Data as a ministry in and of itself is evident throughout Scripture as a God-given gift, from census collection to architectural blueprints to recording lineages. It is requisite for understanding and essential as a guide for righteous Great Commission ministry. The ministry of data must be welcomed, nurtured, stewarded, and funded. Capacity must be expanded with generosity and open hands. Data sharing, data teaching, data interoperability, data access, data contribution, and data stewardship are healthy components of a ministry essential to the service of the body of Christ.

By utilizing existing technologies, platforms, and related connectivity tools, data as a ministry can be properly developed. Online data literacy programs can be included as mainstays in ministerial education. In addition, those who currently work in missional information can remain open to new and innovative, even prodigious opportunities that new tools and perspectives might provide, recognizing that these opportunities are revealed and directed by the Holy Spirit. In promoting data standards and interoperability, new voices and perspectives can be valued and added without compromising the existing integrity of the missional data system as it stands today.

Could the body of Christ, as much as it is able, support the impartation of data competencies not just in local ministries, but in global networks? We recognize this as a part of the development and maturity of the global church. It can be tempting to view data as something clinical, sterile, or even proprietary. But we must not forget what this data is ultimately serving, and who it is ultimately representing—God’s glory reflected among Christ’s bride.

Supporting ministry data is supporting the nervous system of the body of Christ, a system that supports functionality in nearly every aspect of the global missional community. This is indispensable to the accomplishment of the Great Commission. In the decades to come, mission information as a ministry should be prioritized, valued, and embedded as an integral part of the discipleship and maturity of the global church, for the global church, and owned by the global church. We underestimate the value of data as a ministry of the global church to our own detriment. The stewardship of Great Commission data is more indispensable than ever to the pursuit of Great Commission strategy in this digital age.

Endnotes

- Jason Mandryk. Operation World: The Definitive Prayer Guide to Every Nation. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2010.

- Todd M. Johnson and Gina Zurlo, eds. “World Christian Encyclopedia Online.” World Christian Encyclopedia Online, (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, n.d.). Accessed Jun 21, 2023, https://brill.com/view/db/wceo.

- Fortune Business Insights. “The impact of COVID is accelerating digital connectivity trend and it will influence the growth of the Information technology market in the near future.” Accessed June 21, 2023. https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/impact-of-covid-19-on-information-communication-and-technology-ict-industry-102769.

- Richard Edelman. “Pandemic Fuels Culture of Institutional Mistrust.” World Economic Forum. January 13, 2021. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/01/pandemic-mistrust-government-global-survey/.

- “Calvary Chapel Dayton Valley vs Sisolak.” Last modified July 24, 2020. https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/19pdf/19a1070_08l1.pdf#page=12#page=13.

- Samuel Escobar. Changing Tides: Latin America and World Mission Today, 2002.

- Lausanne Movement, “Len Bartlotti – Lausanne Movement.” Accessed July 5, 2023, https://lausanne.org/leader/len-bartlotti.

- “Welcome to the Community of Mission Information Workers!|Community of Mission Information Workers,”n.d. https://www.globalcmiw.org/.

- Joshua Project. “Joshua Project: People Groups of the World | Joshua Project.” https://joshuaproject.net/.

- PeopleGroups.org. “PeopleGroups.Org.” https://www.peoplegroups.org/.

- “Comibam Internacional – Cooperación Misionera Iberoamericana.” https://comibam.org/es/.

- The Movement for African National Initiatives (MANI) Is a Network of Networks Focused on Catalyzing African National Initiatives and Mobilizing the Resources of the Body of Christ in Africa for the Fulfillment of the Great Commission. “The Movement for African National Initiatives (MANI) Is a Network of Networks Focused on Catalyzing African National Initiatives and Mobilizing the Resources of the Body of Christ in Africa for the Fulfillment of the Great Commission.” https://maniafrica.com/.

- Center for the Study of Global Christianity. “Center for the Study of Global Christianity | Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary.” Last modified June 27, 2022. https://www.gordonconwell.edu/center-for-global-christianity.

- Ethnologue (Free All). “The World.” https://www.ethnologue.com/.

- ProgressBible. “ProgressBible.” https://progress.bible/.

- “Etnopedia – Unreached People Profile Translation.” https://etnopedia.org/.

- Fred Zahradnik. “GPS for Driving, Sports, and Boating.” Lifewire. Last modified January 29, 2020. https://www.lifewire.com/gps-for-driving-and-sports-1683301.