Global Aging Population

Current and Future State of Global Aging

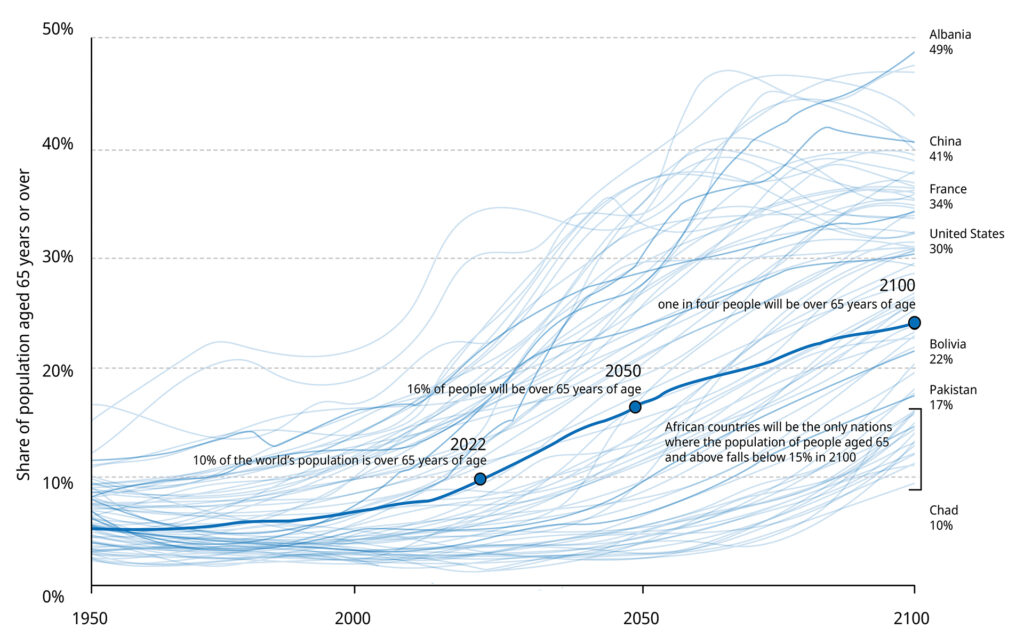

James Hillman writes, ‘The twenty-first century may or may not be greened by ecological awareness, but it will certainly be grayed by its aging population.’1 Global aging is occurring rapidly and will undeniably be a shaping force in our future world.2 The United Nations Population Division estimates that the number of persons aged 65+ is expected to double over the next three decades, such that by 2050 of the global population 65+ will be 16-22 percent.

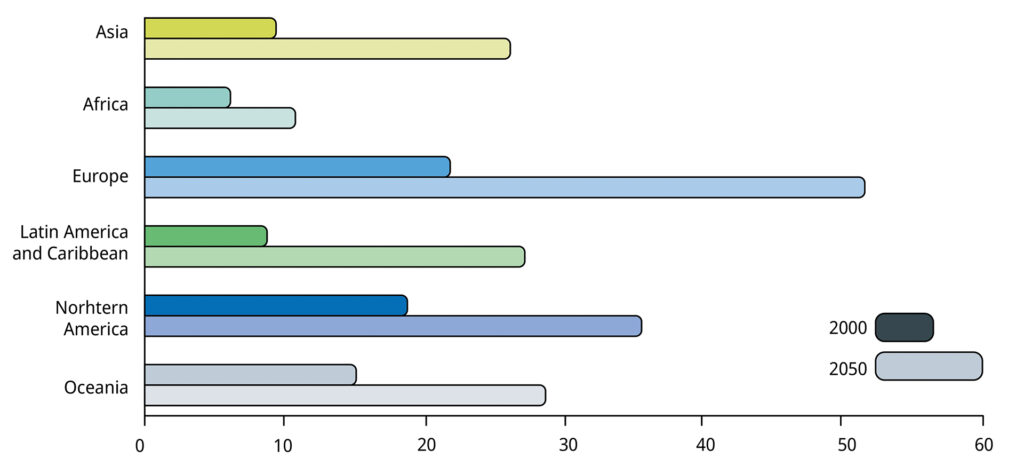

Regionally global aging will vary, yet remain a consistent reality.3 Even in the most demographically-youthful region, Africa, the ratio of those 65+ / < 15 will increase faster (x3) than in either Europe (x2) or North America (x2).4

In short, as summarized by the UN Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs:

- Population aging is unprecedented — It is without parallel in the history of humanity, with more and faster aging to come.

- Population aging is pervasive – It is a global phenomenon affecting every man, woman and child . . . though differently.

- Population aging is profound — It will have major consequences and implications for every region of the world, every socio-economic strata, and all facets of human life.

- Population aging will be enduring — We will not return to the young populations as before.5

The World’s Population is Aging

Global Youth vs Global Aging

The effect of this massive demographic trend will be pervasive, including economics, socio-cultural norms, moral-ethical frameworks, health care infrastructure, geographical migrations, and inter-generational relations. Global aging will also impact the church, discipleship, and the Great Commission. Thus, global aging is a demographic reality presenting the imperative of a corresponding theological and missiological response. Yet, a general review of evangelical initiatives across media, conferences, and training reveals that global aging has not been a high priority beyond worthy small-scale initiatives. Can the church afford to wait for global aging to have momentous impact? This report informs the church about the reality, the opportunities and the challenges of global aging, with the hope that she will be faithful to her Lord and our Great Commission.

Effects of Global Aging

Economic and societal effects

Global aging brings an accumulation of societal burdens, increasing economically non-productive populations, draining pension funds, and increasing health care needs.’6

Medical concerns combined with social isolation compound the economic challenges. In the U.S. there is an estimated USD 6.7 billion in additional Medicare (for seniors) spending annually. In China, because of the long-term care requirements of those 85+, some conclude that long-term care is a threat to the country’s economic growth.7 Of those 85+ projected to be living in 2050, those in China will be 1.4x more than the total number living in the entire world in 2000 and by 2050, 26 percent of the 85+ age in the entire world will live in China, with 8 percent in the U.S.8 Already China is leading worldwide in the total number of dementia cases with 20 percent of global cases, and 1,000,000 new diagnoses/year with an estimated 90 percent not diagnosed. By 2050, about 50 percent of the global dementia cases will be in China; 30 percent in the Americas; 19 percent in Europe and 16 percent in Africa. Through church history, Christians have cared for those in special need, founding hospitals for physical and mental care, leprosariums, ministries for the blind, deaf, disabled, etc. Dementia care is a growing area of special need amongst older adults. There are approximately 9,900,000 new cases globally / year, or a new case every 3.3 seconds.

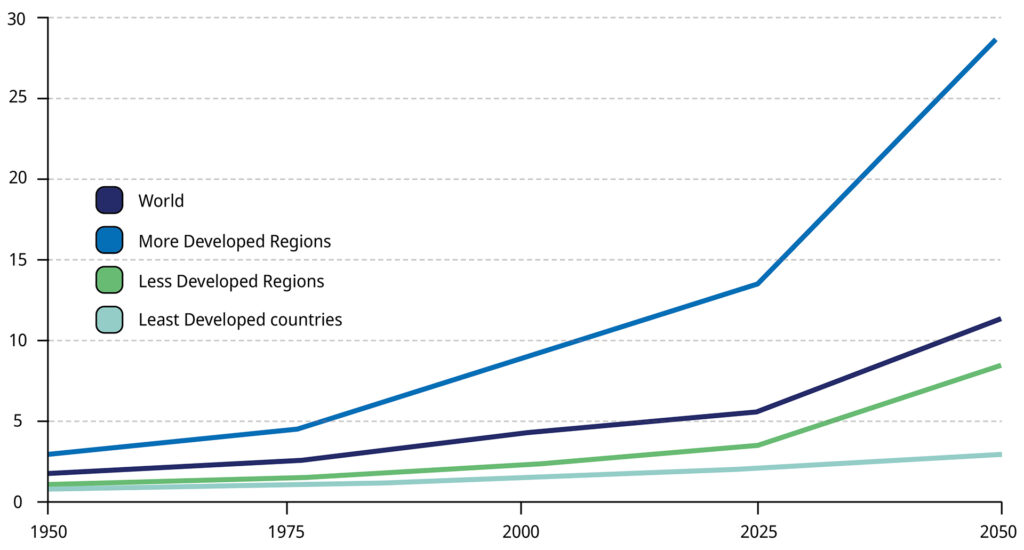

The Old Age Dependency Ratio compounds this challenge; that is, the percentages of the working-age population compared with those needing costly health care threatens every region of the world.9 Coupled with this challenge is the related challenge to those family members responsible for parental support. Typically, the children of the older population are both in the workforce and responsible for caring for their parents. The Parent Support Ratio indicates the gravity of the demographic changes: there are fewer adult children caregivers compared with the number of parents needing support.

The Old Age Dependency Ratio and Parent Support Ratio exacerbate economic pressure on families, but likewise encourage multi-generational households that are better equipped to support one another. Communities able to engage in healthy interdependent relationships between generations will prove more resilient to the challenges ahead.

Old-age Dependency Ratio 2000-2050

Parent Support Ratio 1950-2050

The physical infrastructure of communities—urban and rural—must adapt to accommodate the needs of the rising proportion of those 65+. Accessibility, mobility, public/private transportation, technological changes, health care, and visual and auditory safety all need addressing. Maternity wards, nursery schools, and kindergartens are giving way to care homes and hospices.

Ageism

WHO’s 2021 Global report on ageism states, ‘Ageism refers to the stereotypes (how we think), prejudice (how we feel) and discrimination (how we act) directed towards people on the basis of their age. It can be institutional, interpersonal or self-directed’ and ‘Globally, one in two people are ageist against older people.’10 It has declared ageism a global challenge: ‘Ageism seeps into many institutions and sectors of society including those providing health and social care, in the workplace, media and the legal system.’11 As employment patterns, economic trends, and family structures change, many elderly people will find themselves needing to work in order to survive. But rapid shifts in workplace culture and technology as well as the types of jobs available make this a daunting prospect for anyone 65+ seeking employment. Of the various strategies shown to reduce ageism—policy and law, educational activities and intergenerational contact—we have a role to play.12 In addition, the church must also always be committed to prayer.

Closely associated with ageism is elder abuse. The WHO fact sheet on the ‘Abuse of older people’13 includes the following:

- Around 1 in 6 people 60+ experienced some form of abuse in community settings during the past year.

- Abuse of older people is predicted to increase with rapidly aging populations.

Loneliness and isolation

Loneliness is already a very real issue. The U.K. now has a cabinet level Minister for Loneliness, and in 2023 the U.S. released a special Surgeon General’s report entitled, ‘Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation’.14 Seniors in rural China are often left behind as their children go to the cities for work. A 2016 article from The Globe and Mail states, ‘In some villages [. . .] 30 percent of elderly people kill themselves.’15 In Canada 42 percent of all people aged 85+ live alone. In the U.S. almost one-third of all seniors live alone, and 30 percent self-report loneliness.16

Loneliness and isolation also have health consequences. The National Institute on Aging and the National Institutes of Health summarize, ‘Loneliness acts as a fertilizer for other diseases’ and ‘The biology of loneliness can accelerate the buildup of plaque in arteries, help cancer cells grow and spread, and promote inflammation in the brain leading to Alzheimer’s disease. Loneliness promotes several different types of wear and tear on the body.’17 Additionally, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, mental disorders were more than four times higher among those with feelings of loneliness or isolation. These include major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and probable post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Further, suicide rates for the older demographic are graphic: 25 percent for those 70+ versus 10 percent for all ages.

The Healthcare Management Forum notes, ‘Social isolation is a challenging and persistent issue experienced by many older adults, especially among immigrant and refugee seniors. Unique risk factors such as racism, discrimination, language barriers, weak social networks, and separation from friends and family predispose immigrant and refugee seniors to a higher risk of social isolation.’18 For instance, ‘Canada’s senior immigrant population now makes up over a third of the overall population of older people.’19 The Wellesley Institute notes that 27 percent of recent immigrant seniors perceive their general health as excellent or very good, compared to 52 percent of non-immigrant seniors; 53 percent of recent immigrants perceive their mental health as excellent or very good, compared to 74 percent of non-immigrant seniors.20

With the biblical mandates to honour the elderly as our parents (1 Timothy 5) and to visit and care (James 1:27; Matthew 25), together with the Holy Spirit’s presence and the Good Shepherd’s guidance, we will find many opportunities as well as both ordinary and creative ways of being faithful.

Opportunities for the Great Commission

Spiritual interest of the elderly

Research indicates, ‘seniors value spirituality more as they age’ while noting that ‘a person does not become spiritual just because they get older.’21 The Pew Center’s detailed studies note that ‘By several measures, young adults tend to be less religious than their elders; the opposite is rarely true.’22 Older adults regard religion as more important than those aged under 40 in all but 2 countries of the 114 countries surveyed, as indicated by weekly worship, daily prayer, and reports of the importance for self-identity.23 Globally, 84 percent of adults say religion is an important part of their daily lives.24 It would be wrong to assume that Lausanne affiliates lack opportunity amongst the aging. If anything, the rapidly growing aging demographic grants greater opportunity to engage older adults with the message of the gospel, especially due to the high levels of spiritual practice. Further, in non-Western(-ized) cultures, the sacred/secular dichotomy is much less relevant.25

Ministries for the aging

Caring for our physical health never ends and neither does our spiritual care. Discipleship continues all our days, while the promise of fruitfulness in old age is often overlooked. The contributions and opportunities of the elderly are to be honoured. With the changing demographics within Christianity as well, ministry to and by the older generations must also have a central place in the life of the church.

Why would not parallel programs for seniors pastors and missionaries also be appropriate? And not just specialized programs for one age group (seniors), but an understanding of the full life course of human development for the body of Christ as inherently intergenerational.

Children’s ministry has long been a major focus of Christian activity. Commonly evangelical churches focus on the ‘emerging generations’, with a lesser response to care for and reach out to seniors in the church and community. Already those 65+ are more than those <5, and by 2050 the ratio will be 2:1. Further, by 2050 those 65+ will equal those <15.26 No one challenges the importance of youth pastors. Why the hesitancy for seniors pastors?

Many trust Christ on their deathbed, and many come to faith in older ages. Increasing longevity and the looming shadow of mortality, combined with the evangelistic potency of Christian love and care may create something like a 70-100 Window, similar to the well-known 4-14 Window. A Bible-based theology (and missiology) of pastoral and spiritual care for the aging presents many strategic opportunities and responsibilities.

Grandparents as spiritual leaders

As The Economist stated in early 2023, ‘The age of the grandparent has arrived.’27 There are 1.5 billion grandparents in the world, up from 500 million in 1960. As a share of the population, they have risen from 17 to 20 percent. The ratio of grandparents to children under 15 has vaulted from 0.46 in 1960 to 0.8 today.

By 2050, we project that there will be 2.1 billion grandparents (making up 22 percent of humanity), and slightly more grandparents than those under 15. ’By 2050, 30 percent of China’s population is projected to be grandparents (Bulgaria–29 percent, Mexico—28 percent, the United States and India–24 percent, Senegal–15 percent, Burundi–14 percent). Surely grandparents can be as much a part of the solution to the challenges of global aging as otherwise; for instance, grandmothers regularly care for their grandchildren.28 Also grandparents as mentors continue to prove beneficial.

Care for the caregivers

In Japan 24 percent of caregivers are spouses. BMC Public Health (2022) notes, ‘In Indian households, [the] spouse is the primary person to provide care along with daughters-in-law from the younger generation. Thus, caregivers’ age has a very broad range; older adults can be care-receivers as well as caregivers.’29 One in four Canadians is a caregiver, with 75 percent of caregivers also working. Further, the number of caregivers is likely to double by 2035. In addition, according to the Center for Disease Control (2018), 25 percent of seniors are themselves caregivers. 30 percent of Americans are caregivers; 58 percent are women; 20 percent are 65+; 37 percent are caring for a parent (or in-law).30

Caregiving is taxing; at least one in three report being distressed. Ministries supporting families would undoubtedly be most welcome, an opportunity in itself, and an open ‘back door’ to our neighbours.

Governmental advocacy

There are many avenues for influencing public policy. For instance, age-friendly cities, vaccination policies, housing, climate and aging. The UN ‘Principles for Older Persons’31 is going to be a significant document that will become as important as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Geneva Conventions. It is aligned with the core principles of Independence, Participation, Care, Self-Fulfilment, and Dignity. In addition, the ‘Key Resources’ section below provides more leads and suggestions.

The Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing32 (MIPAA)provides a framework for integrated, wholistic mission, highlighting three priority directions:

- Older Persons and Development

- Advancing health and well-being into old age

- Ensuring enabling and supportive environments

Each of the three has multiple specified issues, followed by multiple objectives, and then suggested actions. For those committed to ‘Integral mission [as] the proclamation and demonstration of the gospel’,33 this is an invitation, if not a call, to such wholistic missional participation as the MIPAA suggests. The dimension of spiritual care, however, is missing.

Key Resources for Global Aging and the Great Commission

Global

- “World Population Aging: 1950-2050” (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division)

- “United Nations Principles for Older Persons” (United Nations Human Rights)

- “The Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing and the Political Declaration” (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs)

- International Federation on Aging

- World Health Organization — Ageing

- HelpAge International

- The Oxford Institute of Population Ageing

Global focus on the rights of older persons

Long-term care

Resources by region (in English)

- Africa

- Asia

- Europe

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Abdulrazak Abyad. “Ageing in the Middle-East and North Africa: Demographic and health trends.” International Journal on Ageing in Developing Countries 6, no. 2 (2021): 112-128.

- Jamie P. Halsall and Ian G. Cook. “Ageing in the Middle East and North Africa: A Contemporary Perspective” Population Horizons 14, no. 2 (2017):39-46.

- North America

Endnotes

- The Force of Character: And the Lasting Life (2000), p. xx.

- The basic reasons are simple: decreasing fertility rate (# of children / women of child bearing age) and increased life expectancy. For a simple chart see WORLD POPULATION AGEING: 1950-2050, p. 5.

- See https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Percentage-of-population-aged-60-years-or-over-by-region-from-1980-to-2050_fig4_344199610

- See WORLD POPULATION AGEING: 1950-2050, p. 16.

- Executive Summary of World Population Ageing 1950-2050. Copyright © United Nations 2002 Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

- The United Nations Population Fund and HelpAge International state, ‘Population ageing is a major global trend that is transforming economies and societies around the world. “Ageing in the 21st Century: A Celebration and Challenge — Executive Summary.” October 5, 2012. https://www.helpage.org/resource/ageing-in-the-21st-century-a-celebration-and-a-challenge-executive-summary/.

- By 2025, 26% of those 85+ in the entire world will be in China.

- http://www.duke.edu/web/cpses/Dudley%20Poston.ppt

- In China there has been a steady decline of the number of working aged adults from 7.8 for economic support of each elder in 1985 to (projected as) 1.6 in 2050.

- World Health Organization. “Global Report on Ageism: Executive Summary.” March 18, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240020504.

- https://www.who.int/news/item/18-03-2021-ageism-is-a-global-challenge-un

- See the United Nations’ 18 ‘Principles for Older Persons’ as one example. https://olderpeople.wales/about/publication-scheme/our-policies/un-principles/

- World Health Organization. “Abuse of Older People. “ June 13, 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/abuse-of-older-people.

- U.S. Public Health Service. Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community. 2023. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-social-connection-advisory.pdf

- The Globe and Mail. “How China’s Rural Elderly Are Being Left Behind and Taking Their Lives.” March 28, 2016. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/world/how-chinas-rural-elderly-are-being-left-behind-and-taking-theirlives/article29179579/.

- Esteban Ortiz-Ospina and Max Roser. “Loneliness and Social Connections.” February 2020. https://ourworldindata.org/social-connections-and-loneliness.

- National Institute on Aging. “Social isolation, loneliness in older people pose health risks.” April 23, 2019.https://www.nia.nih.gov/news/social-isolation-loneliness-older-people-pose-health-risks

- Shanthi Johnson, Juanita Bacsu, Tom McIntosh, Bonnie Jeffery, and Nuelle Novik. “Competing challenges for immigrant seniors: Social isolation and the pandemic.” Healthcare Management Forum 34. no. 5 (2021): 266-271. doi:10.1177/08404704211009233

- Carmen Groleau. ”Culturally focused dementia care needed for Canada’s senior immigrants, researchers say.” March 10, 2022. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/kitchener-waterloo/dementia-care-older-immigrant-population-1.6376972

- Seong-gee Um and Naomi Lightman. “Seniors’ Health in the GTA: How Immigration, Language, and Racialization Impact Seniors’ Health.” Wellesley Institute. May 2017. http://www.wellesleyinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Seniors-Health-in-the-GTA-Final.pdf

- Phillip A. Cooley. “Seniors and Spirituality.” April 17. 2017. http://www.allaboutseniors.org/seniors-and-spirituality.

- Pew Research Center. “The Age Gap in Religion Around the World.” June 13, 2018. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2018/06/13/the-age-gap-in-religion-around-the-world/.

- Pew Research Center. “The Age Gap in Religion Around the World.” June 13, 2018. http://www.pewforum.org/2018/06/13/young-adults-around-the-world-are-less-religious-by-several-measures/. Each of these countries is relatively poor, with a per-capita GDP below $5,000. These figures have remained consistent for decades.

- Pew Research Center. “The Age Gap in Religion Around the World.” June 13, 2018. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2018/06/13/why-do-levels-of-religious-observance-vary-by-age-and-country/.

- Noted benefits of religiosity and spirituality include: An optimistic outlook on life and illness, facing life with more resilience and hope; improved social and familial relationships; coping better with such life stresses as financial, health, and other crises; a greater ability to cope with illness, disability, and death; lower mortality rates and improved health recovery outcomes; a sense of community and thus the avoidance of social isolation; involvement with volunteer activities, keeping connected with others; a sense of purpose in life; personal sharing of their health and well-being; the exchange of ideas and information. Zachary Zimmer, Carol Jagger, Chi-Tsun Chiu, Mary Beth Ofstedal, Florencia Rojo, and Yasuhiko Saito. “Spirituality, religiosity, aging and health in global perspective: A review.” SSM – Population Health 2 (December 2016): 373-381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.04.009.

- https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/files/documents/2021/Nov/undesa_pd_2002_wpa_1950-2050_web.pdf, p. 16.

- The Economist. “The Age of the Grandparent Has Arrived.” January 12, 2023. https://www.economist.com/international/2023/01/12/the-age-of-the-grandparent-has-arrived.

- For the statistics for the U.S., https://www.apa.org/pi/about/publications/caregivers/faq/statistics.

- R. Chakraborty,, A. Jana, and V.M. Vibhute. “Caregiving: a risk factor of poor health and depression among informal caregivers in India- A comparative analysis.” BMC Public Health 23, no. 42 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14880-5.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Caregiving.” August 2018. https://www.apa.org/pi/about/publications/caregivers/faq/cdc-factsheet.pdf.

- United Nations Human Rights. “United Nations Principles for Older Persons.” December 16, 1991. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/united-nations-principles-older-persons.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. “Madrid Plan of Action and its Implementation.” April 2002. https://www.un.org/development/desa/ageing/madrid-plan-of-action-and-its-implementation.html.

- From The Cape Town Commitment, ‘It is not simply that evangelism and social involvement are to be done alongside each other. Rather, in integral mission our proclamation has social consequences as we call people to love and repentance in all areas of life. And our social involvement has evangelistic consequences as we bear witness to the transforming grace of Jesus Christ. If we ignore the world, we betray the Word of God which sends us out to serve the world. If we ignore the Word of God, we have nothing to bring to the world.’