Rise of Africa

Introduction

Paul rejoiced with the Colossians, that in their day, the gospel was growing and bearing fruit all over the world (Colossians 1:6). Similarly, we thank God, in gratitude for the well accepted fact that Christianity has experienced rapid growth in Africa over the last century. According to the latest edition of the World Christian Encyclopedia, 26 percent of all Christians live in Africa, granting that Africa holds about 18 percent of the total world population. In relative terms, Africa has the highest percentage of the Christians in the world, followed by 24 percent in Latin America, 23 percent in Europe, 15 percent in Asia, 11 percent in North America and 1 percent in Oceania.1 Indeed, God has remembered his love and faithfulness to Israel, and all the ends of the earth have seen the salvation of our God (Psalm 98:3).

The Rise of Africa

While the spread of the gospel testifies to the power of the Holy Spirit, the historic advance of Christianity in Africa has not happened in a vacuum. The continent has undergone monumental waves of social transformation that influence how we imagine the task of the Great Commission in coming decades. For a long time, poverty and disease, underdevelopment, poor political leadership, and lack of modern infrastructure put the continent far behind other regions of the world in terms of social progress. In recent decades, four markers of change have progressively yielded a new narrative, broadly seen as ‘Africa Rising’.

An increase in democratic political space

Despite lingering pockets of political instability and recurring flareups, Africa on the whole enjoys greater democratic freedom than it did prior to the 2000s, and when conflict occurs, it is resolved in far less time. This stability facilitates other positive changes.

Visible economic growth

We can see this through a number of developmental indexes. For example, lower child mortality rates, improved access to healthcare, and increased access to formal education at higher levels all contribute to better life outcomes. Young Africans are harnessing the fields of technology, fashion, music, education, entrepreneurship, and financial venture to move the continent from the margins of world affairs into the global limelight. Deep-seated afro-pessimism has given way to the realization that Africa is an emerging market for global goods and services and holds essential raw materials for global industries. This reappraisal does come with new modes of exploitation, yet for Africans, access to previously out-of- reach global platforms offers a more level playing field.

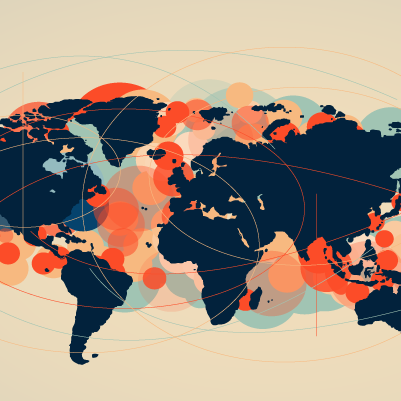

Global attention due to population growth

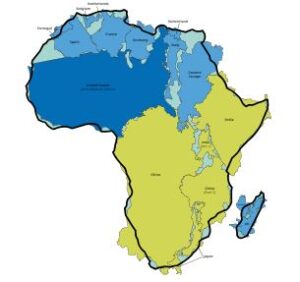

The True Size of Africa’ map produced by Kai Kruse (http://kai.sub.blue/en/africa.html)

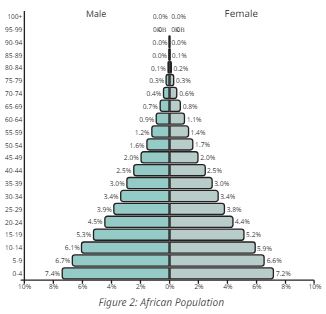

As of 2023, Africa’s population is close to 1.4 billion, 15 percent of which is under the age of 15. The population is further expected to double by 2050.2 The projected increase is expected to be concentrated in a select number of already densely populated countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Tanzania. At the same time, in terms of landmass and relative to other continents, Africa is more than capable of holding this population.

Incredible urbanization

At 47 percent urbanization, Africa is experiencing one of the world’s fastest rates of urbanization, catching up with much of the rest of the world in this respect. This growth includes infrastructural growth—albeit indebted—innovation to the housing sector, revalued land-rights, crowded high-rise buildings, and fewer of the squalid slums of yesteryear. Reinvigorated cities increasingly feature gleaming skylines and plush housing suburbs alongside consumer retail, local and regional transportation networks, local and international telecommunications, and sporting and entertainment industries. Regional integration and access are creating larger consumer bases.

Prospects for the Great Commission

The four key changes above, namely increase in democratic space, visible economic uplift despite lingering marginalities, rise in populations, and fast urbanization, ought to foreground missional engagement across the continent. Several key areas of focus are highlighted below.

Reaching students at all levels

First, the transition of the African population curve has produced a higher population base, forming a pyramid structure. Exponential growth in the formal education sector correlates with this shift. From 2000 to 2010, nearly all African countries experienced marked advances in primary and secondary school enrollments, and in entrepreneurial tertiary education. Higher education supports democratizing nations and stabilizing economies, thus is a desired good. Education has also been behind the rise of a self-consciously globalizing and technologically and culturally savvy young adult population.

A significant focus needs to go towards evangelizing and discipling students at all stages. In this next phase of Christian mission, it is absolutely vital that outreach and discipleship are focused on emerging adults as they enter tertiary education in colleges and universities. The thriving work of locally led, alumni-funded student ministries such as FOCUS Kenya (Fellowship of Christian Unions) and all related IFES (International Fellowship of Evangelical Students)-affiliate university student ministries—like NIFES-Nigeria, GHAFES-Ghana, and IFES Afrique Francophone—offer particularly instructive models of how to evangelize young adults in this next stage of the African continent. FOCUS Kenya in particular has had enormous impact and may provide models of how to reach university students where such work has not taken root. This is vital, as the college-educated population will grow into a middle-class that will influence trajectories of the rest of the society.

Attention on the transmuting middle-class

In the post-war decades, Western society underwent a similar phase of growth as Africa’s current experience. The western middle-class grew from young people who graduated out of universities to become lawyers, doctors, lecturers, managers, administrative experts, entrepreneurs, and a supportive blue-collar class in stable employment. While conditions of changing job markets will not produce long-term stable professions, a substantial, though not representative, middle-class base is taking shape in Africa. This raises questions about patterns of secularization and desacralization of the public sphere and the privatization of faith. While societies differ in their exact conditions, it is incumbent on churches to raise awareness of the possibility that up-and-coming generations will increasingly find church irrelevant. A lot of emphasis in this last phase of the African church’s growth has been on church planting, largely focused on conversion and numerical increase. Beyond numerical increase,it is not clear that any substantive segment of African churches is investing in the shaping of a Christian vision addressed to metamorphosing (literally changing frequently) populations. Theological curricula in seminaries that train pastoral clergy have a role to play in forming such a vision, but there is more to such a vision. In the face of multiple competing secularized visions that entirely edit out spirituality, there is an urgent need for churches to invest consciously in inspiring a biblically shaped ethical and moral vision for their societies.

While societies differ in their exact conditions, it is incumbent on churches to raise awareness of the possibility that up-and-coming generations will increasingly find church irrelevant.

Reassessing resource dependencies and conditionalities of past mission encounters

If indeed Africa’s material conditions have improved, credit is due in part to the Western church—primarily large faith-based organizations like World Vision, Compassion International, Food for the Hungry, and Tear Fund, along with numerous other Western-funded Christian organizations that have pioneered in the betterment of material conditions. This fact cannot be denied. Even individual missionaries, short-term mission teams, and community-based initiatives have shown great solidarity with Africa’s impoverished communities through a wide variety of microfinance projects, especially in supporting women, child sponsorship, and orphanages. Recently, doing business as mission has joined the refrain of doing good business to advance material well-being in the name of Christ. In and of itself, economic and even consumer growth for a perennially disenfranchised populace is a desirable good championed by Christian mission.

Looking to the future, important questions must accompany these efforts, particularly as development-oriented work in Africa is backed by ‘Mission Inc’ in the West.3 The relationship between Christian compassion on one hand and material dependency (rather than faith) on the other hand must be attended to. Questions of power relations in the co-dependencies, despite collaborative intentions, require reflexive self-awareness on the part of the outsider missionaries and donor-communities. Similarly, tension between genuine material need and accumulative consumerism devoid of a well-grounded theological vision cannot be ignored in the emergent Africa. Further, as Western economies change (decline?) it will be necessary to reassess the patterns of supply and access to institutional resources from the West with attention to the sustainability of organizationally dependent mission initiatives.4

Mission: Retrospect and Prospect

In a 2010 centenary review of the Edinburgh Missionary Conference of 1910, in a chapter aptly titled, ‘A New Era of Mission is Upon Us’, Robert Priest summarizes four eras that broadly shaped Protestant mission in the previous century.5 From 1792, William Carey typified the first era when he called for missionaries to establish the church outside of Christendom. From 1865, in the second era, Hudson Taylor mobilized a generation to focus on geographically inland regions that had not had any contact with the gospel. William Cameron Townsend, founder of Wycliffe Bible Translators (1942) and Summer Institute of Linguistics (1934), exemplifies the generation of the third era, with a focus on ‘unreached ethnolinguistic people groups’ through Bible translation. A fourth era, as Robert Priest sees it, echoes Ralph Winter in the World Christian Perspectives Movement—the ‘kingdom era’ where mission came to be understood in holistic terms attending to broadly material needs alongside evangelism. The African continent has been the beneficiary as a missionary receiving continent through these phases of frontier, hinterland, unreached, and humanitarian and holistic mission. Latterly, Africa has come to significantly shape the narrative of World Christianity, evidenced by the claim that the numerical strength of the church has shifted to the Global South, along with the nascent narrative of reverse missions. This is the context for imagining what mission engagement in Africa needs to look like going forward. In this next phase, granted the changing population and social dynamics, what Africa needs is to cultivate an integrated theological vision in order to establish the gains of all the evangelistic mission efforts.

In this next phase, granted the changing population and social dynamics, what Africa needs is to cultivate an integrated theological vision in order to establish the gains of all the evangelistic mission efforts.

African youth

Churches need to be attuned to the relative youthfulness of the population. Socialization that accounts for a Christian vision cannot be left to state educational institutions, although states should be encouraged to continue to be responsible in promoting formal education. Spiritual formation involves more than youth ministries. It includes the cultivation of a theological habitus that is resiliently pro-youth through intentionally well-discipled churches and church-formed educational institutions. This incontrovertible value of young people for the mission of God is well attested to in the Old Testament. Consider Joseph, David, Jeremiah, Josiah, Daniel, Esther, Ruth, as well as many of Paul’s companions like Timothy and Silas.

Developing an ethical and moral vision

Africa needs a Christ-inspired ethical and moral vision that is attuned to an emergent middle-class demographic. The church’s tendency has been to casually castigate material well-being, failing to consider the implications of material uplift for a continent persistently ravaged by poverty. A thoughtful moral and ethical vision will be much more helpful, as a significant portion of the population is poised to join the middle-class amid inequality. Such a vision must attest to the authenticity and credibility of Christian witness in the public arena beyond the walls of the church.

Theological deepening and consolidation

It is improper to parrot the notion that African Christianity is a mile wide and an inch deep, or that it is devoid of theological training and resources. In recent decades, much Christian mission effort has gone into starting Bible schools, seminaries, and universities led by local leaders and faculty. In Ghana, for instance, churches have upgraded their seminaries into universities, such as Central University, Pentecost University, and Regent University of Science and Technology. In Kenya, government regulations required an upgrade of seminaries into universities. In Southern Africa, the influence of digitalization has enhanced access to Christian education. Further, global organizations like Langham Publishers, Oasis International, and Tyndale House among many others support theological publishing and access to theological material in Africa. The Africa Leadership Survey revealed that Africans are in fact avid readers of the Bible and a variety of devotional and theological books.6 ScholarLeader Foundation supports the formation of Christian leaders at the highest levels of education. Advances in technology and accessibility have greatly improved biblical literacy, although it is an ongoing work. Africa is also home to robust Christian radio and TV industries, which disseminate preaching and Christian music. With that said, questions of evangelism and related church planting activities need to be explored from a variety of practical angles, including more professional training and preparation, resource accountability, and necessary ecclesial institutional scaffolding.

Preserving African Christian witness

African Christianity across the board remains patently culturally and theologically conservative, regardless of denominational affiliations. However, competing Christian polarities, often originating from outside the continent (especially from America), have a huge polarizing influence on the witness of the African church within its own continent. Christian leaders, missionaries, and partners will need to think about how these imported rivalries are diluting Christian witness. African Christian leaders must consider the competing theological visions of Christianity (Christianities?), and not just those inspired by a Western liberal progressive moralism.

Improvement of theological curricula

While Africa benefits from a proliferation of theological institutions, a wide variety of seminaries, Bible institutes, and Christian universities are still largely shaped by Western missions in structure and curriculum design. Grassroots church leaders often appraise these as foreign to African needs because they tend to provide generic curricula that still look more Western than African. Much thought needs to go into reviewing the relationships between training institutions and churches.

Development-oriented mission

Another lingering concern is about development-oriented missionary activity. While attending to social needs is worthwhile, the wide variety of church-related entrepreneurial activity often preoccupies the core witness of the church. Although a great deal is done in the name of Christian mission, it is not clear that biblically formed theological frameworks have been articulated around these activities, or if those who benefit from these services recognize the difference between Christian organizations and global aid organizations. Quite a bit of literature addresses itself to the fact that the church is the new NGO—non-governmental organization—or rather, FBO—faith-based-organization. A similar critique is leveled against popular Christian media establishments, focused at once on merchandizing a Christian message while lacking a clear biblically-sound theological ethos. These matters are not any different from what is happening in other contexts such as the United States where pragmatic contingencies shape much of Christian activity, but they need to be part of a self-reflective consciousness among African Christians as the church continues to grow.

Continuing participation of women in mission

Women form a significant part of the church in Africa. The last several decades have brought recognition of girls’ education across Africa. It is said that to educate a girl is to lift up the whole village. While patriarchy remains a feature of political cultures of much of the region, there has been progress in terms of educational empowerment of girls and the rising public profiles of women. Correspondingly, even though it is observable that women are the majority in churches in Africa, their representation in leadership is minimal, and in some churches it is non-existent. Continued empowerment of women as equal partners in the mission of God alongside the men is going to play a significant role in advancing the cause of mission locally and abroad.

Challenging unbiblical practices and facing new social problems

Certain cultural practices must continue to be challenged. For example, people with disabilities have historically experienced stigmatization in Christian communities. Disability and chronic sickness are often perceived as a curse or a punishment from the gods/ancestors due to some abomination committed by the person, a relative, or an ancestor. Unfortunately, this belief often leads to harmful practices of exorcism instead of increasing the accessibility of ministries. A related issue is the victimization of children and older women through witchcraft accusations, which the church cannot ignore. As with all urbanizing contexts, an emerging problem is the labor and sexual exploitation and trafficking of girls and women. African populations are also experiencing a resurgence of traditional cultural practices that are antithetical to a Christian vision, many of them re-energized by globalization, electronic media access, and economic opportunism. In addition, the church must stay vigilant to the agendas of multiple interest groups inside and outside the continent that pursue God-denying intentions amongst the growing young adult population.

Islamic witness and Christian-Muslim conflict

Although the church’s growth is celebrated, religious change is not exclusive to Christianity. Islam has been growing exponentially. The Muslim north remains largely unevangelized, while the two religions meet at the Sahel. Mission organizations like SIM and WEC which were originally Western now recruit African missionaries to the Muslim world, while indigenous mission organizations like Nigerian-based CAPRO are reaching out into Muslim countries. Proclamation witness and church planting into the majority Muslim north may be the vital breakthrough of the next few decades.

No amount of social transformation can displace the need for the gospel of Jesus Christ. Indeed, there will always be new generations that need to hear and be shaped by a gospel vision, because the only enduring power to transform the human condition is the gospel of Jesus Christ.

Meanwhile, Christian-Muslim conflict persists. While countries like the Gambia and Senegal offer models of peaceful coexistence, countries on the Sahel boundary line are experiencing tensions. Christians in boundary areas have often been victimized by terrorist anarchy. As populations are expected to increase, conflict will continue to be a fraught issue, especially when politically motivated and resource-driven, as in northern Nigeria and the horn of East Africa. It is critical for Christians to discern underlying issues and engage in appropriate dialogue, inter-faith cooperation, reconciliation, and civic mobilization of respective authorities. Certainly, evangelism among majority Muslim communities remains a core focus.

Conclusion

As the Psalmist sang long ago, Ethiopia (Africa) has indeed stretched out her hands to God as she brings her tribute of praise to God alongside the nations (Psalm 68:31–35). Along with Israel, she who was once desolate is now called Hephzibah, ‘The Lord delights in her, she belongs to the Lord’ (Isaiah 62:4). Yet, as Isaiah saw in that ancient day, those who call on the name of the Lord today on behalf of Africa cannot give themselves rest. While we rejoice in God’s amazing grace towards the continent in this last remarkable century of growth, there is scarce room to sink into complacency concerning the Great Commission. The enemy prowls around seeking to devour (1 Peter 5:8) through human sin and multiple expressions of cultural, political, and corporate evil. No amount of social transformation can displace the need for the gospel of Jesus Christ. Indeed, the social transformation that Africa is currently undergoing underscores the urgency of the Great Commission. There will always be new generations that need to hear and be shaped by a gospel vision, because the only enduring power to transform the human condition is the gospel of Jesus Christ. The commission to make disciples, baptize, and disciple remains imperative. Let Africa rise indeed. With her, let us all rise to the occasion to bring the gospel of him of whom the increase of his government and peace there will be no end (Isaiah 9:6–7).

Endnotes

- Todd M Johnson and Gina Zurlo. World Christian Encyclopedia, Third Edition (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020).

- 2022 Revision of World Population Prospects. United Nations. https://population.un.org/wpp/.

- See: Jonathan Bonk et al. The Realities of Money and Missions: Global Challenges and Case Studies (Pasedena, CA: William Carey, 2022).

- See Paul Bendor-Samuel. ‘Mission, Power, and Money.’ in Missions and Money: Global Realities and Challenges (Pasedena, CA: William Carey, 2022) 138.

- Robert Priest. ‘A New Era of Missions is Upon Us’ in Evangelical and Frontier Mission: Perspectives on the Global Progress of the Gospel. Beth Snodderly and A. Scott Moreau, eds. (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2011) 294-304.

- See Robert Priest and Kirimi Barine. African Christian Leadership: Realities, Opportunities, and Impact (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2017).