The New Middle Class

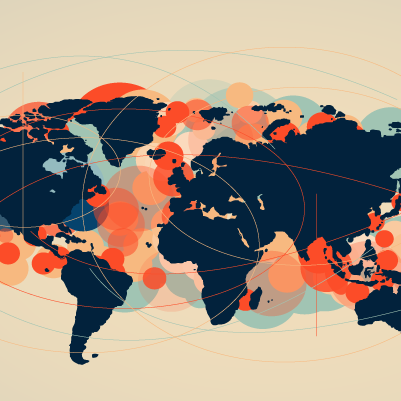

In 2018, for the first time in human history, ‘the majority of humankind [was] no longer poor or vulnerable to falling into poverty’.1 This enormous shift has fueled the historic growth of the global middle class.

This demographic represents unique opportunities and challenges for the global church. With more affluence, higher levels of education, and more social mobility, the middle class requires a unique way of connecting with people as compared to other segments of society such as students or the global poor. Urban ministry has rightly received much attention, but it is important to recognize that more people are found in suburban communities—where the middle class tends to live—than in the city core. As cities grow, the middle class tends to grow as well.

This demographic represents unique opportunities and challenges for the global church.

The definition of who is considered middle class varies from country to country. The changing demographics of different countries create unique trajectories for mission efforts. In this paper, we will explore the middle class in three different countries with different trajectories over the next 25 years, namely the demographically stagnant middle class in the United States (US), the slowly declining middle class in China, and the rapidly expanding middle class in India. Taken together, these snapshots help us to address the unique situations of the middle class globally and consider the significant implications of this massive demographic for global mission.

Standing Stagnant: The middle class in the United States

The US has enjoyed a strong and growing middle class since the end of World War II. The Evangelical church in the US has largely been a middle class phenomenon, and the missionary movement has benefited from the growing US middle class over recent decades. Economic momentum, high immigration levels, and the relative wealth of the middle class all but guarantee that it will continue to exist as a significant constituent of the US population.

Patterns of the US Middle Class

The Pew Research Center defines the middle class in the US as households with an annual income that ranges from USD 48,500 to USD 146,000 for a family of three—ie between 67 percent and 200 percent of the median US household income. Based on this definition, approximately 52 percent of the population belong to the middle class. 2

Income levels seem to correlate with church involvement. Using data from the Cooperative Election Study, a prime source of sociological data in the United States, Ryan Burge has found that, ‘the people who are the most likely to attend services this weekend are those with college degrees making $60K-$100K. In other words, middle class professionals.’3 In the United States, educated, middle class, married people are more than twice as likely to go to church as those without these three attributes.

Immigrants continue to come to the US to avail of economic opportunities, usually joining the middle class within a few years. In 2019, 14 percent of the US population were foreign-born, compared to only 5 percent in 1980. 4 Within a generation, many immigrant families have higher household incomes than their non-foreign-born counterparts. Even so, the US middle class population is likely to remain static given the falling fertility rates for the majority population.

Barriers to the Great Commission in the US

The authors of the 2023 book The Great Dechurching warn, ‘We are currently in the middle of the largest and fastest religious shift in the history of our country.’5 Affluence and the attendant secularization may be ending decades of US religious interest, with this trend strongest in the middle class. This may have grave consequences for the traditional sending and funding of missionary efforts, including support for disaster relief, literacy programs, and other aspects of global mission.

In a polycentric world, non-Western giving to global missions should certainly grow, but there is still a need for Christians in the US to continue supporting global missions. The US middle class is wealthier than its global counterparts. There is an urgent need to disciple church members to overcome instant gratification, entitlement culture, self-interest, and discontentment.

Finally, political divisions are driving much of the current US narrative, including within the church. Racial tensions, sexual dysphoria and the acceptance of radical gender ideologies, and a debate over socialist policies lie at the heart of this division. Syncretism also poses a great threat to the middle class in the US. Reaching this middle class for the Great Commission requires us to discern wisely, love incarnationally, witness effectively, and use apologetics appropriately.

Opportunities for the Great Commission in the US

A significant opportunity in the US is the growth of diaspora congregations. Immigration to America may revive both its church and its middle class.6 Current rates of immigration are at record levels, and many local churches are deeply involved in ministry to these communities. Diaspora populations in the US go through an assimilation process that stresses family dynamics, religious worldviews, and social relationships. The increased affluence associated with joining the middle class contributes to the changes these families experience. Whereas first generation immigrants typically stay within the immigrant community, second and third generation immigrants do not. This constitutes a significant opportunity for the church. Assisting these families through difficult transitions opens the door to the gospel.

The US continues to be the dominant sender and financer of missions globally. Even though contemporary global missiology is often seen through the lens of immigration and diaspora, the sending, training, and financing of global missions will continue to be a significant part of the US missionary movement. The overall percentage of missionaries in the global workforce is smaller because of increasing numbers from non-Western nations.7 Yet, the overall number of American missionaries has remained at about the same level over the past few years. In 2010, there were about 127,000 American missionaries, increasing to about 134,000 in 2016.8 The middle class supports most of the American missionaries and will continue to do so if the church remains healthy.

Much of the giving in the US is not from the wealthy, but from the lower and middle class.9 The Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability has reported increased giving by evangelicals every year over the past ten years, with international giving increasing over two percent in 2022. According to Christianity Today, even during the pandemic, giving has increased.10 A healthy American middle class into the future can be expected to continue funding global missions as long as the church maintains its numbers.

Slow Decline: The middle class in China

Between 1990 and 2019, the top 40 countries experienced per capita gross domestic product (GDP) growth from 2x to 6x, while China grew at an unprecedented 32x.11 In 2011, the definition of household incomes per capita per person per day for the middle class globally was USD 11 to USD 110. In terms of purchasing power parity (PPP), the annual household income for a four-person middle class household would be USD 14,600 to USD 146,000.12 Based on this definition, the size of the global middle class was estimated at about 90 million in 2006 and 730 million in 2016. By 2027, the size of the middle class in China is expected to exceed one billion people.13

By 2050, China’s population is expected to decline to 1.3 billion, from 1.4 billion in 2022.14 The decline is due to China’s one-child policy from 1980 to 2015. However, even after the government loosened this restriction, few people in China are interested in having more children, as it is expensive to raise them.15 Starting around 2030, the slowing Chinese economy is likely to lead to a slow decline of the Chinese middle class.16

Patterns of the Chinese Middle Class

In 2021, China formulated an ‘internal circulation’ strategy with a focus on domestic consumption and sustainable development to counter the decline in foreign investment. It included proposed measures for better work-life balance, including reducing long working hours known as ‘996’ (ie 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week).

China could get older before it gets richer, with 330 million people expected to be above the age of 65 by 2050. The one-child policy produced a society marked by a 4-2-1 pyramid, where families have four grandparents and two parents who look to their only child to care for them in old age. Additionally, many new entrants to the middle class in China choose to prioritize their careers, as reflected in the decline in marriage registrations since 2013.17

The zeitgeist of the middle class is a consumerist lifestyle fueled by discretionary income. This is the central difference with the poor. Consumerism is the engine of all modern economic systems18, and the middle class is the biggest consumer market in China. The biggest challenge of the Chinese middle class church is ‘mammon’. The most common expressions of mammon include workaholism, high levels of comfort, materialism, security, financial independence, self-sufficiency, social symbolism, and individualism. These adversely lead to detachment, isolation, nominalism, and syncretism. Similar middle class patterns can be seen in other countries. These different frontline middle class challenges are often mutually reinforcing and hard to solve through a piecemeal solution. Evangelism to this demographic calls for a ‘whole-life discipleship’ approach, where the cross is an integral commitment and not just an option.19

Barriers to the Great Commission in China

Government Suppression

During the 19th National Congress in 2017, China ended the separation of the Party and the State, returning to the ‘Party and State’ system, similar to the pre-reform era before 1978. The 2017 Congress also promulgated a holistic view of national security through technology and grid-based management for all services. Since 1949, China has promoted a formula of ‘Marxism plus Chinese context’, albeit recently adding the phrase ‘Chinese excellent traditional culture’, which explains the shift towards Chinese ethnocentricity at the core of China’s nationalistic ideology.20 This systemic control can stifle the freedom to be a disciple of Jesus.21

Prevailing Stigmas

The survey results of 120 Protestant pastors in 15 Chinese cities between 2017 and 2019 suggest that the CCP has been wary of Protestant churches for the following reasons:

- Faith is seen as an ideological threat, as Protestants are more loyal to an authority other than the party.

- Foreign connections are seen as a tool of the West to subvert China and are therefore viewed as an internal security threat.

- Churches regularly organize and mobilize followers and contribute to a vibrant civil society. 22

Further insights can be discovered in the Lausanne paper.23

Opportunities for the Great Commission in China

Ministry of Presence

For the first time in the last few decades, China is seeing more people at home due to old age, unemployment, childbirth, or other emerging cultural trends like ‘Tang Ping’ or ‘Lying Flat’. It is an alternative form of rebellion by doing the bare minimum for daily living in response to social pressures.24 This presents an opportunity to minister to families through meeting their need for belonging.25 This ministry can also be practiced by addressing the ‘996’ work culture.26

Whole-life Discipleship

God created us to have a relationship and to partner with him to fulfill the creation mandate. We are called to advance God’s kingdom in our homes, in our neighborhoods, and through our work. One avenue for this which may be particularly effective in ministering to the Chinese middle class is ‘Triple Listening’, where we listen to cries of the world, the wisdom of the Word, and each other’s frontline stories. Next imagine what God wants us to do and respond contextually to the needs before us.27

Public Theology

The educated middle class is looking for a common theology28 that analyzes Chinese history, culture, philosophy, and religion to address socio-political movements in a contextual way from a Biblical point of view.29 This is a promising opening for the Great Commission.

Rapidly Expanding: The middle class in India

The development of India’s middle class has its origins in the English education system introduced during the colonial era in the 19th and 20th centuries.30 Consequently, after the independence of India in 1947, the middle class received increased opportunities and rapidly expanded after the economic liberalization reforms of the 1990s. The size and definition of the middle class has been debated and dependent on several factors like income, status, education, identity and power, consumption, occupation, and lifestyle.

The Indian think tank, the People Research on India’s Consumer Economy (PRICE) identifies a household as middle class if it has an annual income of Rs 5–30 lakh (USD 6,700–40,000). Their recent survey found that the middle class in India has expanded from 14 percent of the total population in 2004-2005 to 31 percent in 2020-21 and is projected to rapidly expand to 63 percent by 2047,31 contingent on stable political and economic reforms.32

Today, the Indian middle class ranks third globally after China and the United States. By 2035, it is expected to be the largest. One survey suggests that with India’s rapid expansion, it could ‘add an additional one billion consumers to the global middle class between 2016 and 2050’.33

Characteristics of the Indian Middle Class

India’s middle class can generally be categorized as:

- Privileged and enthralled by English, equipped with education and high-end skills, and attaining to white collar jobs and stable income.

- Global yet local and traditional yet modern in their culture, social norms, education, career pursuits, and overall outlook.

- Materialistic, pragmatic, and aspirational, but religious.

- Dominated mainly by the upper caste.

- Recognized by their consumerist lifestyle and identity.

As for their religious tendencies, this demographic’s worldviews are different from other classes and are changing rapidly due to various factors, particularly among the educated middle class. It is important to note that the spirituality of the Indian middle class is multifaceted and blurred with the practical issues at hand. Almost all the cults, the New Religious Movements (NRM), and gurus strive to appeal to such followers appropriately while addressing issues pertaining to them, such as peace at home, success at work, resolving health and relationship issues, and blessings on children’s education and career. Modern spirituality is best at reinterpreting old philosophical beliefs and traditions in modern-day language with practical applications.

Barriers to the Great Commission in India

The combination of India’s religious, deeply caste-based social structure with this secular and pluralistic context poses a huge challenge in presenting the uniqueness of Jesus Christ. Along with caste, consumerism and materialism, the nexus between corporate institutions, religion, and politics is posing a new set of challenges.

Further, it is necessary to avoid overemphasizing Christian dogma, rituals, traditional beliefs, and practices that are not biblical. Contextualizing Christian faith and focusing on experiential theology (Anubhava) needs attention. Misconceptions about Christianity—mainly that it is a Western religion—call for scholarly and historical correction.34 In fact, the church existed in India from AD 52 when the apostle Thomas arrived in South India, but this history is largely unknown to Indians today. Meanwhile, the annual death anniversary of the Apostle Thomas is celebrated as Indian Christian Day. The Indian church and missions excellently engage with tribal, outcaste, and lower caste groups, however, effective missional engagement and research for the Indian middle class still lag behind.

Opportunities for the Great Commission in India

Considering the Indian middle class’s unique characteristics noted earlier, gospel engagement requires a distinct, relational, friendly, and at times intellectual approach that will incorporate the necessary practical help to address their felt needs and challenges. It is essential that the whole church is discipled, equipped, and nurtured to live out the gospel. While building a relational approach, house churches utilizing family networks among the Indian middle class must be acknowledged. The Christian middle class needs to be strategically equipped to see ‘work’ and ‘vocation’ as God-given opportunities to fulfill the creation mandate while fulfilling the Great Commission in workplace engagement. Hence, equipping Christian professionals for workplace and marketplace engagement is vital.

A significant portion of the Indian middle class—particularly those most urbanized, globalized, educated, and financially secure—are not necessarily convinced by and dedicated to the teachings of their religion. Many would be open to listening and changing their view if invited to do so in a way that speaks to their experiences and needs. The Indian middle class will be a key field of mission in the 21st century and beyond.

Summary

It is estimated that by 2050, the middle class of the United States, China, and India will total a combined two billion. Mission to the middle class is marked by a robust engagement with both the positive and negative implications of consumerism. It must also be characterized by an integrated approach of both philosophy and strategy. This demands whole-life discipleship, fulfilling the creation mandate through our work, developing a culture of incarnational service, and investing in God’s kingdom through time, talent, and treasure.

Endnotes

- Are You in the Global Middle Class? Find out with Our Income Calculator.’ Pew Research Center. Accessed 4 May 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/07/21/are-you-in-the-global-middle-class-find-out-with-our-income-calculator/.

- “Are You in the Global Middle Class? Find out with Our Income Calculator | Pew Research Center.” n.d. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/07/21/are-you-in-the-global-middle-class-find-out-with-our-income-calculator/.

- Ryan Burge. Religion Has Become a Luxury Good, (graphsaboutreligion.com) Accessed 16 September, 2023.

- “Racial Wealth Snapshot: Immigration And The Racial Wealth Divide » NCRC.” n.d. Accessed 20 June, 2023. https://ncrc.org/racial-wealth-snapshot-immigration-and-the-racial-wealth-divide/.

- Jim Davis, Michael S. Graham, and Ryan P. Burge. The Great Dechurching: Who’s Leaving, Why Are They Going, and What Will It Take to Bring Them Back? (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2023) p. XX.

- Dany Bahar and Greg Wright. ‘Immigration as an Engine for Reviving the Middle Class in Midsized Cities.’ 18 November 2021. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2021/11/18/immigration-as-an-engine-for-reviving-the-middle-class-in-midsized-cities/.

- Gina A. Zurlo, Todd M. Johnson, and Peter F. Crossing. ‘World Christianity and Mission 2020: Ongoing Shift to the Global South.’ International Bulletin of Mission Research 44, no. 1 (2020): 8–19. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/2396939319880074.

- Peggy E. Newell. North American Mission Handbook: US and Canadian Protestant Ministries Overseas, 2017-2019 (Pasadena, CA: William Carey Publishers: 2017).

- ‘Who Gives Most to Charity?’ Philanthropy Roundtable. Accessed 8 May 2023. https://www.philanthropyroundtable.org/almanac/who-gives-most-to-charity/.

- Hannah McClellan. ‘Evangelical Giving Goes Up, Despite Economic Woes.’ Christianity Today. 30 November 2022. https://www.christianitytoday.com/news/2022/november/state-of-giving-donations-parachurch-megachurch-finances.html.

- Zak Dychtwald. ‘China’s new innovation advantage.’ Harvard Business Review. 2021 May-June. https://hbr.org/2021/05/chinas-new-innovation-advantage.

- Homi Kharas. ‘The unprecedented expansion of the global middle.’ Brookings Institution. 28 February 2017. https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-unprecedented-expansion-of-the-global-middle-class-2/.

- Homi Kharas and Meagan Dooley. ‘China’s influence on the global middle class.’ Brookings Institution. October 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/FP_20201012_china_middle_class_kharas_dooley.pdf.

- Department of Economic & Social Affairs. ‘World Population Prospects 2022: A Summary of Results.’ United Nations. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/World-Population-Prospects-2022.

- Laura Silver and Christine Huang. ‘Key facts about China’s declining population.’ Pew Research Center. 5 December 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2022/12/05/key-facts-about-chinas-declining-population/.

- Donghyun Park and Kwanho Shin. ‘Impact of Population Aging on Asia’s Future Economic Growth, 2021-2050.’ Asian Development Review 40, no. 1 (March 2023). https://www.adb.org/publications/asian-development-review-volume-40-number-1.

- Charlie Campbell. ‘China’s Aging Population Is a Major Threat to Its Future.’ TIME Magazine. 7 February 2019. https://time.com/5523805/china-aging-population-working-age/.

- Kerryn Higgs. ‘A brief history of consumer culture?’ Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press Reader. 11 January 2021. https://thereader.mitpress.mit.edu/a-brief-history-of-consumer-culture/

- Matt Jolley. ‘What is whole-life disciple?’ London Institute of Contemporary Christianity. Accessed 30 August 2023. https://licc.org.uk/resources/what-is-a-whole-life-disciple/.

- John Zhang. ‘Ministry Insights under a Nationalistic Trend.’ China Source Quarterly. 13 March 2023. https://www.chinasource.org/resource-library/articles/ministry-insights-under-a-nationalistic-trend/.

- Philip Le Feuvre’s 1980 Lausanne Occasional Paper ‘Christian Witness to Marxists’ is one of the most comprehensive papers on communism, covering basic Marxist characteristics, reviewing successes and failures, and charting evangelistic strategies for pre-revolutionary societies in developing countries, developed Western societies, and post-revolutionary societies like Europe. Philip Le Feuvre. ‘Lausanne Occasional Paper: Christian Witness to Marxists.’ Lausanne Movement. June 1980. https://lausanne.org/content/lop/lop-12.

- Sarah Lee. ‘Pastors in China’s New Era.’ China Source Quarterly. 13 March 2023. https://www.chinasource.org/resource-library/articles/pastors-in-chinas-new-era/.

- See Lausanne consultation paper on Witnessing to the Marxist.

- Lily Kuo. ‘Young Chinese take a stand against pressures of modern life — by lying down.’ The Washington Post. 5 June 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/china-lying-flat-stress/2021/06/04/cef36902-c42f-11eb-89a4-b7ae22aa193e_story.html.

- Shuya Kim. ‘New era and new roles: Changes & Issues for Chinese Ministries in a new context.’ China Source Quarterly. 13 March 2023. https://www.chinasource.org/resource-library/articles/new-era-and-new-roles/.

- One helpful resource on this topic is the Theology of Work Project (https://www.theologyofwork.org/), which provides a commentary on all the books of the Bible in traditional and simplified Chinese. It also has devotions for professionals, Bible studies for small groups, sermons for pastors, and resources for scholars.

- ‘Wise peacemakers: How to love your culture by triple listening (1/5).’ London Institute of Contemporary Christianity. https://licc.org.uk/resources/wise-peacemakers-part-1-of-5/.

- Jacob Chengwei Feng. ‘Chinese Theology for English-Language readers.’ China Source. 13 March 2023. https://www.chinasource.org/resource-library/articles/chinese-theology-for-english-language-readers/.

- A Chinese Bible commentary, similar to the South Asia Bible Commentary, could also help develop indigenous public theology. Brian Wintle. ‘South Asia Bible Commentary: A one volume commentary on the Whole Bible.’ Themelios 41, no. 2. https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/themelios/review/south-asia-bible-commentary-a-one-volume-commentary-on-the-whole-bible/.

- Vinita Pandey. Crisis of Urban Middle Class (New Delhi: Rawat Publications, 2009).

- Rajesh Shukla. ‘Gearing Up For a Billion-Plus Middle Class by 2047.’ PRICE. 2023. https://www.price360.in/publication-details.php?url=gearing-up-for-a-billionplus-middle-class-by-2047.

- BW Web Team. ‘One out of every three Indians “middle class”; to double by 2047: Report.’ Business Standard. 2 November 2022. https://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/every-one-in-three-indians-middle-class-to-double-by-2047-report-122110200522_1.html.

- Abhijit Roy. ‘The Middle Class in India: From 1947 to the Present and Beyond.’ Asian Politics 23, no. 1 (2018). Retrieved from https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/the-middle-class-in-india-from-1947-to-the-present-and-beyond/.

- Pius Malekandathil. ‘St. Thomas Christians: A Historical Analysis of their Origins and Development up to 9th century AD.’ in St. Thomas Christians and Nambudiris, Jews and Sangam Literature: A Historical Appraisal, Bosco Puthur (ed.) (Kochi: LRC Publications, 2003), 1-48.