People on the Move

Introduction

Since the dawn of civilization, human beings have been on the move. Some people move in search of greener pastures, to find livelihood, to seek safety, for education, in search of employment, join family, for trade, to engage in business, or for sheer survival. Others move to escape from conflict, wars, violence, or persecution. Still others move because of adverse living conditions resulting from socioeconomic disruptions, natural disasters, or political upheavals. Human migration is a major global reality today and everyone is impacted by its far-reaching repercussions.

As we approach the end of the first quarter of the 21st century, the people on the move worldwide have accelerated to unprecedented levels.

Human movements have emerged as one of the defining issues of our times as more people now live in a place other than where they were born than at any time in recorded history. The urge, scale, volume, speed, and direction of human migration have escalated to record levels over recent decades. As we approach the end of the first quarter of the 21st century, the people on the move worldwide have accelerated to unprecedented levels. Human migration has become so pervasive since 2000 that the United Nations has designated December 18 of every year as ‘International Migrants Day’ and declared 2015 as ‘The Year of the Migrant’.

The goal of this article is to develop a comprehensive understanding of the contemporary issue of the movement of people and awaken the global church to understand the diasporic nature of the Christian faith and missional opportunities arising out of the large-scale human displacements. It hopes to help Christians grasp how the dispersed are transforming and advancing Christianity and to mobilize and resource the global church to engage and leverage diaspora communities worldwide.

World on the Move: We Are All Migrants

We are all either migrants or descendants of migrants. The story of some form of displacement is woven deeply into our very being, as it was for our ancestors so will it be for our progeny. Humankind is a migratory species. Modern societies, nations, economies, and politics have evolved from repeated human displacements. People move from the countryside to urban centers then to other cities and countries. While modes of economic activities evolve with the hopes of a better life, others are forced to move for survival in the face of life-threatening circumstances, violence, instability or persecution.

All migration research and forecasts predict that global human migration will continue to surge in the coming decades, and it will remain a central issue worldwide. The shift to renewable energy, inflationary pressure on national economies, new technologies of mobilities, autonomous vehicles, artificial intelligence, robotics, etc. will generate massive disruptions in our current socioeconomic order and it will not pan out fairly for all people in every nation, which in turn will increase outmigration out of many nations. We are at the cusp of a quantum leap in human mobility with flying cars, hyperloop, and supersonic planes. The depopulation of some urban centers, aging nations, and demographic shrinking of some nations will result in massive population shifts. Pandemics, inflation, climate change, wars, etc. will force more people to explore more livable places elsewhere in the world. All of that means more people will move in the next three decades than in the previous three centuries.

Growing Numbers: Data and Trends

A reliable source of most current data on global migration is hard to come by. The figures used by policymakers, demographers, government statisticians, census data scientists, journalists, nonprofits, and the public at large differ widely depending on their sources, definitions, methodologies, and the purpose of their reports. Another fact that makes this task challenging is that these data are dynamic and ever-changing. Counting migrants of many different kinds in different parts of the world on a regular basis is nearly impossible. Moreover, by the time any migration report is published, it may be considered obsolete, although it does not mean it is unhelpful at all.

The International Organization of Migration (IOM) of the United Nations tracks human migration from every nation and reports figures and trends by publishing a flagship report called the World Migration Report (WMR). The WMR 2022 estimates that there were 281 million international migrants in the world in 2020, which amounts to 3.6 percent of the global population. Only one in 30 people in the world are migrants and the vast majority of people live in the countries where they were born, though many migrate to other places within their countries. Back in 2010, there were only 220 million international migrants in the world (about 3.2 percent of the world population) while in 2000, there were 173 million international migrants in the world (which constituted about 2.8 percent of the world population). In 1990, there were 152 million (2.9 percent), and in 1980, there were 102 million (2.3 percent), while in 1970 there were 84 million recorded international migrants in the world. In 2020, around 3,900 migrants were reported dead or missing globally, which is less than 5,900 in 2019, though the actual number of casualties will be countless more and continues to surge year after year.

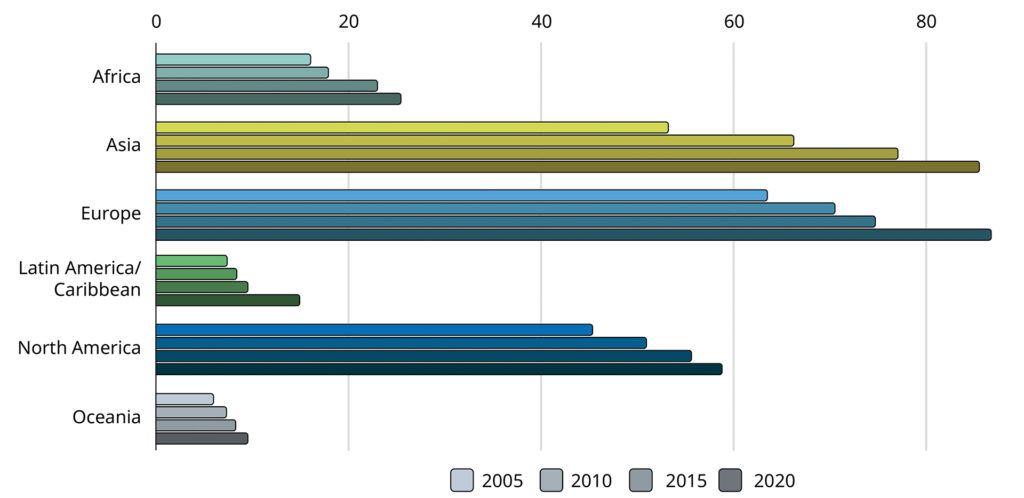

Figure 1: International migrants by major region of residence 2005-2020 (in millions)

Europe is currently the largest destination for international migrants, with 87 million (30.9 percent of the international migrants), followed closely by Asia with 86 million international migrants living there in 2022. North America is the destination for 59 million international migrants (20.9 percent), followed by Africa with 25 million migrants (nine percent). Over the past 15 years, the number of international migrants in Latin America and the Caribbean has more than doubled from around seven million to 15 million, making it the region with the highest growth rate of international migrants and the destination for 5.3 percent of all international migrants. Around nine million international migrants live in Oceania, or about 3.3 percent of all migrants.

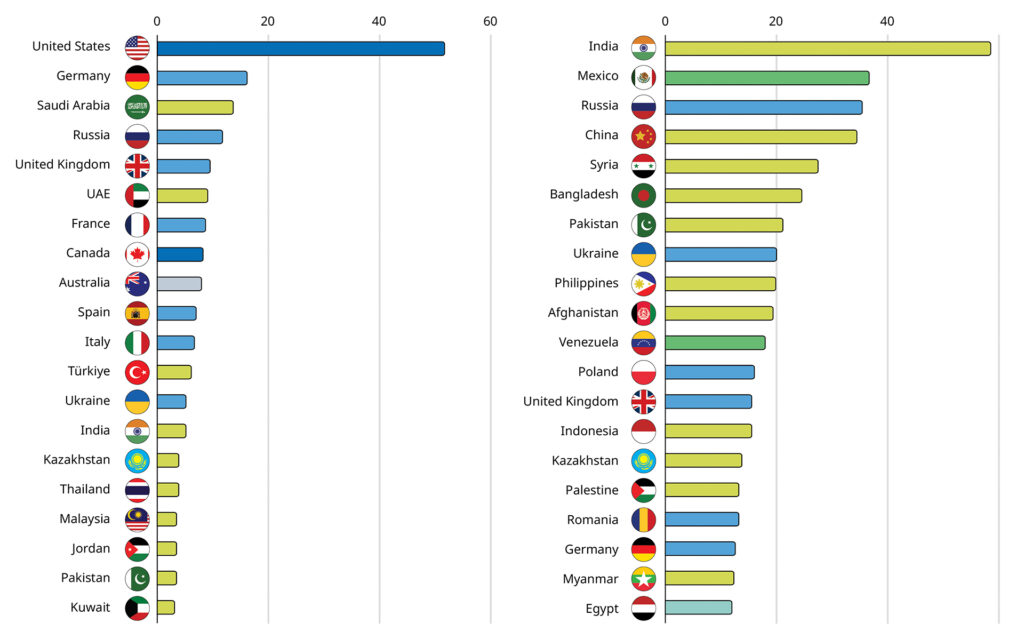

As India became the most populous nation in the world in 2023, it also has the highest emigrant population in the world (18 million). The next most migrant-sending countries are Mexico (11 million), Russia (10.8 million), and China (10 million). The fifth most migrant-originating country is the Syrian Arab Republic with eight million, mostly as refugees because of the large-scale displacement arising out of war in the region over the last decade. The United States remained the largest migrant destination country in the world over the last 50 years and had 51 million international migrants as of 2022. The next most prominent destination is Germany, with nearly 16 million international migrants while Saudi Arabia is the third largest destination country at 13 million. Russia had 12 million and the United Kingdom had nine million migrants.

Figure 2: Top 20 destinations (left) and origins (right) of international migrants in 2020 (millions)

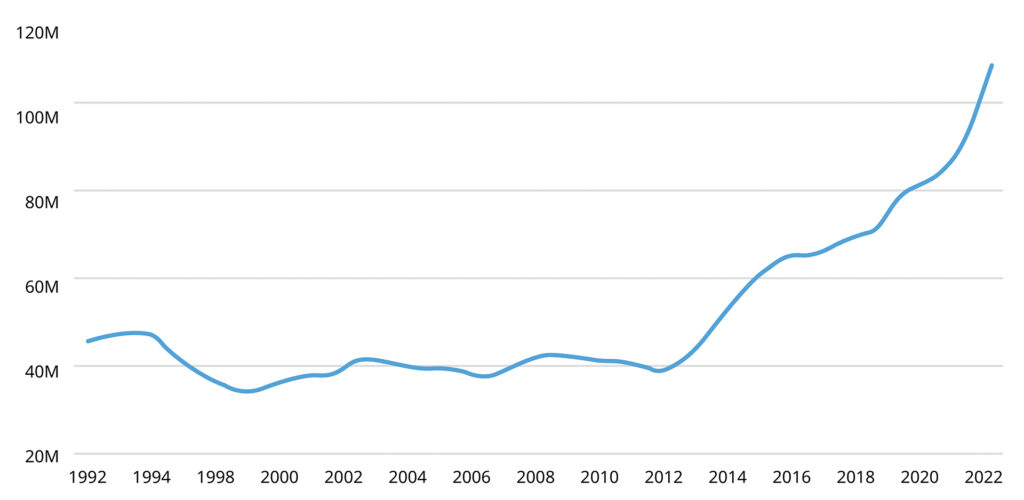

According to the UNHCR, by the end of 2022, there were 108.4 million people forcibly displaced in the world as a result of persecution, human rights violation, war, violence or events seriously disturbing public order. This includes refugees, internally displaced persons, asylum seekers, and others in need of international protection. There were 35.3 million refugees and 5.4 million asylum seekers in the world as of 2022. IDPs surged steeply in recent years to reach an all-time high of 62.5 million people in the world in 2022. About 52 percent of the refugees came from three countries namely, the Syrian Arab Republic (19 percent), Ukraine (16 percent), and Afghanistan (16 percent). The major refugee hosting nations are Turkey (3.6 M), Iran (3.4 M), Colombia (2.5 M), Germany (2.1 M), and Pakistan (1.7 M).

Figure 5: Forcibly displaced people in the world 1992-2023 (in millions)

All the above figures and explanations fail to portray the scenario of contemporary global migration fully and accurately. The People on the Move is a fast changing reality worldwide, and all figures and charts are outdated and do not depict ground realities. All data cited here would be superseded by more current data and readers are advised to visit the cited sources for the latest figures and trends in global migration. This makes the study of migrants and diaspora communities extremely challenging as well as exciting, as the number of migrants are ever evolving and all trends are constantly shifting.

Finding the religious faith of immigrant communities is still harder to come by. The number of immigrant churches in Western nations are a fast-evolving reality that remains under the radar of host nation Christians and are generally underreported in Christian databases. Since most immigrant churches begin informally at homes or use rented facilities to conduct services in foreign languages with strong ties to their ancestral homelands, it is difficult to precisely assess the proliferation of new migrant churches worldwide. Christianity in the West is not declining, but immigrants from Asia, Africa, and Latin America are reviving it and transforming it with renewed missional thrust.

People on the Move and Christian Mission

God is sovereign over human history and human dispersion. The Apostle Paul in his Areopagus address at Athens during his second missionary journey clearly states:

And He has made from one man from every nation of mankind to live on all the face of the earth, having determined allotted periods and the boundaries of their dwelling place, so that they should seek the Lord, and perhaps feel their way toward Him and find Him. Yet, he is actually not far from each one of us; ‘for in Him we live and move and have our being’; as even some of your own poets have said, ‘For we are indeed His offspring.’ (Acts 17:26–28)

The fact that God creates nations (Genesis 25:23; Psalm 86:9-10), God made provision for language and culture (Genesis 11:1, 6, 7, 9) and he determines the spatial and temporal dimensions of our habitation (Acts 17:26), serves missional purposes to bring God glory, to edify people, and bring salvation to the lost. The displacement makes people inquisitive of others, question their inherited belief systems—marginalized in new settings, and seek devotion beyond the gods of the land to a Savior who is universal beyond territorial deities. The dispersion of people is within the redemptive plan of God for human history. From the perspective of the doctrine of the priesthood of all believers, diasporas are the fulfillment of God’s plan for a worldwide mission that may be called the ‘missionhood of all believers’. Every nation counts on the presence, participation, and power (either good or bad) of diasporas (short-term, long-term, or those with acquired citizenship). All missionaries are migrants for having to cross national or cultural boundaries. Likewise, all Christian migrants could be considered potential missionaries as they carry out the missionary functions of diffusing the gospel cross-culturally.

The term diaspora is widely used to describe all people who live in a place other than where they were born. Another associated Greek word is ecclesia, meaning ‘gathering’, which is often translated as ‘the church’. God gathers scattered peoples while the gathered ones are scattered for his mission in the world. The scattering and gathering of people are twin corresponding, interrelated, and mutually reinforcing archetypes to understand the mission of God in the world in the twenty-first-century context where mission flow, resources, and influence can arise from anywhere in the world and be directed anywhere else in the world. As we now live in an unprecedented age in the history of Christianity when there are Christians in every country of the world (geopolitical entity, not ethno-linguistic group), the gospel has truly reached the ends of the earth and is bouncing back from the edges to gain new momentum worldwide. The radical reversal in the cultural and demographic composition of the global church is rendering a new face of Christianity and forging new collaborative alliances that will accelerate global missions in the 21st century.

The diaspora factor forces us to consider Christianity as a universal faith with great diversity within and a healthy sense of mutuality with each other globally. It accelerates the advance of the gospel and mission work gains new momentum on account of diasporas. It enables the margins to become new centers of Christianity while remaining local everywhere. It is pneumatologically empowered global missiology that unleashes the missional potential of every Christian everywhere together to hasten the mission of God in the world. Christian mission is no more from the West to the rest, but from everywhere to everywhere. It allows multiple centers of Christianity, and the missionary flow occurs in many different directions (polycentric and omnidirectional). Everywhere has become a mission field as well as a mission force.

Diaspora Missions

The field of diaspora missions seeks to explore the challenges and opportunities of Christian missions among the dispersed peoples of the world, considering their unique cultural, social, and religious contexts. Diaspora missions are the ways and means of fulfilling the Great Commission by ministering to and through diaspora peoples.

The diaspora factor forces us to consider Christianity as a universal faith with great diversity within and a healthy sense of mutuality with each other globally.

Diaspora missiology needs to be differentiated from traditional missiology along four distinctive lines such as its perspective, paradigm, ministry patterns, and ministry style. While the traditional missiology was geographically defined (leading to foreign vs. local or urban vs. rural), diaspora missiology is non-spatial since the unevangelized people cannot be solely defined geographically anymore and they are not bound within any national boundaries or latitudes. It challenges numerous established mission strategies such as the 10/40 window and geopolitical designations. The traditional missiology concentrated on the Old Testament paradigm of come (gentile-proselyte) and the New Testament paradigm of go (Great Commission), while diaspora missiology in contrast focuses on the new reality of the 21st century where people are viewed as moving targets and mission as moving with the target audiences. In traditional missiology, the ministry pattern was sending missionaries and providing financial support while diaspora missiology recognizes a new way of doing mission among and with people who are at our doorsteps and with every Christian as a missionary.

Diaspora mission embraces the growing reality of contemporary mass movement of people which results in an interconnected world and the inevitable formation of diverse and multicultural communities in various countries. Consequently, traditional mission approaches that were primarily centered around sending missionaries to foreign countries, now need to engage the diaspora populations everywhere. The former mission-sending nations have now become mission fields and some of the migrants from former mission fields are engaged in reaching fellow immigrants and peoples of their host nations. The world is now in our neighborhoods and all Christians need to be awakened to this reality and equipped to reach all people everywhere. Diaspora mission demands the need to contextualize the Christian message and practices to multiple specific socio-cultural and religious contexts in multiple locations simultaneously. It requires everyone in every church to bear Spirit-empowered Christian witness to all people every day. It emphasizes the role of Christians in host countries as bridge-builders between diaspora communities and the local church by acting as advocates, mediators, and translators, to facilitate dialogue and provide help to integrate well into the society while being transformed through relationships.

Furthermore, diaspora missions often encourage multilingual ministries as most migrants retain their native languages. Since all spiritual matters are often sensed in heart languages, learning foreign languages, teaching dominant languages of the host nations, and offering small groups and church services in multiple languages become vitally important. Diaspora missions also recognize, value, and leverage the transnational ties of diaspora communities to have a kingdom impact by building partnerships with families and churches in their ancestral homelands.

The nature of diaspora communities whose relationships, resources, and influences between nations transcend geopolitical conceptions of missions is very transnational. Diaspora missions involve a holistic approach that addresses the spiritual, social, and practical needs of the diaspora communities in a foreign land by providing social services, language classes, job assistance, and community support besides gospel sharing, especially those displaced under dire circumstances. It addresses issues of identity, belonging, social cohesion, and intercultural competencies as people navigate their lives in foreign lands while gradually, over time and generations, assimilating into host realities and maintaining (declining, for some,) ties with ancestral homelands. Overall, diaspora missions encompass a global multi-directional view of Christianity where mission occurs from everywhere to everywhere.

Diaspora missiology is conventionally divided into three paradigms: First, Mission to the Diasporas, which focuses on ministering to unreached peoples of the world who are now living among or near to Christians and how congregations in receiving countries can practice missions at their doorsteps by reaching the newcomers in their neighborhood without having to go abroad. The uprooted and transplanted peoples are open to the gospel in foreign lands and do not have any socio-cultural hindrances or inhibition to switch faith allegiance. They compare and contrast their inherited faith with those of others and come closer to the gospel witness after moving to new locales, especially those coming from regions where Christianity is a minority faith or Christians are persecuted. The people in transition are more receptive to the gospel and in need of Christian hospitality and charity.

Overall, diaspora missions encompass a global multi-directional view of Christianity where mission occurs from everywhere to everywhere.

The second paradigm is Mission through the Diasporas, whereby the diaspora Christians are evangelizing their kinsmen in their adopted homelands, and other fellow immigrants from other parts of the world. These migrants serve as cross-cultural missionaries just as all missionaries are migrants. It is the physical displacement of Christians that causes the gospel to diffuse across cultures to new people in new places. Moreover, Christians make up the largest religious diaspora and are more open to going to ‘the ends of the Earth’ than others, knowing they will find Christians no matter where they go. The truism may hold some ground that ‘if you are Christian, you will travel and if you travel, you will become a Christian.’

Thirdly, there is Mission beyond the Diasporas, wherein diaspora Christians are engaged in reaching members of the host nation, have missional influence on people back in their homelands or minister across geographies and cultures to other peoples. Diaspora peoples are cross-cultural bridges with an uncanny ability and experience in multiple worlds, who need to be mobilized as self-supported missionaries to have gospel impact on their immediate physical settings as well as their wide relational networks. They become natural translators, always explaining one world to the other thus transforming into evangelists of their views and beliefs. Since migratory displacement is fundamentally a theologizing experience, they seek to answer deeper questions about life, purpose, and ultimacy. Their spiritual vitality and insights are a tremendous asset to any existing congregation in the host society and they are motivated to establish new faith communities.

Diaspora missions is not just about ministering to four percent of the world’s population who are international migrants, nor is it the latest fad in mission studies. Since all of us are migrants and not native to the places we call home, we must view the Christian faith as diasporic. Christian faith is always moving because our God is always on the move. Christian doctrines and theology of mission need to be reconceived as God on the Move (Motus Dei), for all static conceptions of God are idolatrous, as they are territorial and oppressive, making their devotees motionless and lifeless. The Christian faith cannot be bound to a location or domesticated by any people because its nature is to break free of the prisons we enshrine it in. Seeing God as a living and moving being on mission is consistent with the biblical, historical and ongoing work of God in a moving world.

Christianity is a missionary faith par excellence since it is a faith that was born to travel

Conclusion

Christianity is a missionary faith par excellence since it is a faith that was born to travel. In fact, the mobility of its adherents and the moving nature of God are what make the Christian faith a transportable and translatable faith, as it continually transcends borders of all kinds over time. Seeing God as a moving being and his ongoing work as a result of the moving of God is a helpful way to develop a theology and missiology for a world in motion. The migrants, displaced, and diasporas are at the forefront of God’s mission in the world today. As evident in the earlier eras of Christianity, the people on the move are powerful agents of growth, spread, and transformation of God’s work in the world and will continue to shape the contours of the advancement of Christianity in the 21st century and beyond.

Note

This position paper was prepared by the Diaspora Issue Network of the Lausanne Movement. The principal author is Dr. Sam George and was written in August 2023. This paper was developed with inputs from the executive team of the Global Diaspora Network, comprising Dr. T.V. Thomas (Malaysia/Canada), Dr. Bulus Galadima (Nigeria/USA), Rev. Barnabas Moon (South Korea), Rev. Art Medina (the Philippines), Dr. Paul Sydnor (France), Rev. Joel Wright (Brazil/USA), Dr. Elizabeth Mburu (Kenya), Dr. Hannah Hyun (Australia/South Korea), Dr. Jeanne Wu (Taiwan/USA), Dr. John Park (South Korea/USA), and Dr. Godfrey Harold (South Africa).

Endnotes

- UN Migration. “World Migration Report.” Access August 15, 2023. https://worldmigrationreport.iom.int/.