‘We Want to Work with You, Not for You’

This was the entirely understandable summary from three Indonesian mission agency leaders as they reflected on the interactions between their own organizations and those with an international structure.[1]

Speaking of such reasonable desires for mission partnership, Webster comments:

The answer does not lie in the patterns of dependence or independence, but in the recovery of that interdependence of the one spirit that marked the New Testament churches. In this basic spiritual unity and interdependence of the younger and older churches today lies the future of the church’s mission to the world.[2]

Few would argue with these fundamental biblical principles. Yet many have struggled to see them applied. At a missionary conference under the slogan ‘Partnership in Obedience’, a visiting Indonesian pastor commented to a Dutch professor, ‘Yes, partnership for you, obedience for us.’[3]

That such experiences persist is a cause for lament. That they do so when the Majority World now sends more workers than the West is a cause for serious reflection on the international mission agency model.[4] What needs to change? What new models might we pursue? Ones that promote humility, not hubris; mutuality, not management; and collaboration, not control.

And how might Majority World agencies and churches encourage those of us in the West to ground our good intentions for mutual mission sending partnerships across the world church?

The Challenges of the International Model

For all the talk of polycentrism in mission circles today, in international mission organizations, it is often the multinational structure that persists. Internationalization strategies that added sending bases in other Western nations have in more recent years simply expanded to include countries across the Majority World.

Whilst this ambition to widen mobilizing reach has been well intentioned, such organizations are left grappling with the consequences of a centralized structure, leadership, language, culture, and decision-making processes: ‘The organization may be international in personnel, but Western in organization and structures.’[5]

Kang-San Tan explores the consequences further, stating that ‘. . . there remains a huge risk that power is not decentralized.’[6] He proposes a way forward that would necessitate Western mission leadership to be ‘radical rather than reformist, and willing to make intentional structural changes rather than engage in mission theories and rhetoric.’[7] The key question is what might those changes look like? Further, are such radical changes possible in large international organizations where decision making can be slow, history hard to unpick, and the hold on control hard to let go of?

The organization I help to lead—the UK based mission agency UFM Worldwide—has been reflecting heavily on such issues. Given the challenges outlined above, we have been asking how we might partner with emerging Majority World mission sending movements, without expanding our structures into those countries. What follows are three practical examples of how we have been looking to do that.

Stepping Back Before Stepping Forward: Passing on our structures in Brazil

For driven mission practitioners, the development of structures is usually more appealing than closing them down or stepping away. But if there really is a time for everything under the sun, then we must hold more lightly to our organizations.

For over 50 years, UFM worked in partnership with two other Western mission organizations in Brazil, creating an organization called MICEB.[8] This ‘field structure’ was like so many others: properties, vehicles, agency-led projects and strategies. In God’s goodness it was used wonderfully, and many came to know the Lord. A small plaque in the entrance to the UFM office even honours the memory of three mission partners martyred as they took the gospel to an unreached tribe.

But time moved on, churches were established, the context changed. Radically. So, what should we do with the old Western mission structure?

It was a privilege in November 2021 to take part in a special nationalization conference for MICEB. At this conference the leadership of MICEB was passed to four Brazilian leaders from AICEB, a denomination numbering nearly 600 churches, with which UFM workers served over the years.[9] MICEB will now become the locally-led mission agency for AICEB as they send more Brazilians into overseas mission.

The stepping back from a historic structure full of stories, sacrifice, and memories was not without pain. Yet from it a new, locally-led, mission sending structure has been put in place. Could those who came before have wished for a more thrilling legacy than that?

The future relationship between MICEB and UFM is under discussion. The warmth of fellowship over the years means there is a natural desire for partnership into the future. Could the UFM pastoral team assist Brazilian mission partners serving in Europe? Might Brazilians be facilitated to come and serve in the UK? What can Brazilian mobilizers teach the UK church about prayerfully seeing a new generation of gospel workers trained and equipped for service?

Partnership not Paternalism: Revisiting our relationships in Côte d’Ivoire

One of the key strategic oversights of international mission organizations appears to be a tendency to neglect the mission sending structures that God has already set up across the world—namely local churches and their leaders. Any Western involvement in mission sending should be exercised at the request of national churches to partner, not the desire of the Western organization to grow.[10]

One of the key strategic oversights of international mission organizations appears to be a tendency to neglect the mission sending structures that God has already set up across the world—namely local churches and their leaders.

It is in this vein that UFM has recently revisited its historic partnership with the local Ivorian denomination UEESO-CI.[11] UFM has a long history of work in the country, but today there are no UFM mission partners serving there. Indeed, the church is now sending mission partners of its own, particularly into neighbouring Liberia. The president of the denomination, Gueu Siméon, has invited UFM to partner with them to train, send, and support this new generation of mission workers they are sending.

UFM is not aiming to expand its organizational structures into Côte d’Ivoire to facilitate this. Rather, we have been supporting the structures that are already in place, sharing our experiences of mission sending that can be grounded into the Ivorian context by Ivorian leaders.

This new partnership has been initiated by our brothers and sisters in West Africa and we have no executive function in their work. We trust this will mitigate against the dangers of paternalism and allow a genuine partnership to flourish as we witness together this exciting work that the Lord is doing in raising up a new generation of Ivorian mission workers.

Collaboration not Control: A new network promoting mutuality in mission sending

In exploring partnerships in mission sending across the global church, could it be that our instincts have become too structural? Might it be that our development of organizations is hindering the very thing we want to achieve, with our structures limiting the sending of workers for cultural or financial reasons?

This was our observation during our time serving in Indonesia. Agus was a godly Bible college student with a strong passion for mission.[12] The Lord had laid a burden for Japan on his heart. We encouraged him to pursue a summer placement there and connected him with friends serving with an international mission organization in that country. The short summary of the story is that the inflexibility of the financial system of the Western agency became an immovable barrier to him joining their organization.

Might there be an alternative to large multinational mission agency structures? Something that retains the benefits of international relationships but keeps decision-making and appropriate mission sending models truly in the hands of those on the ground.

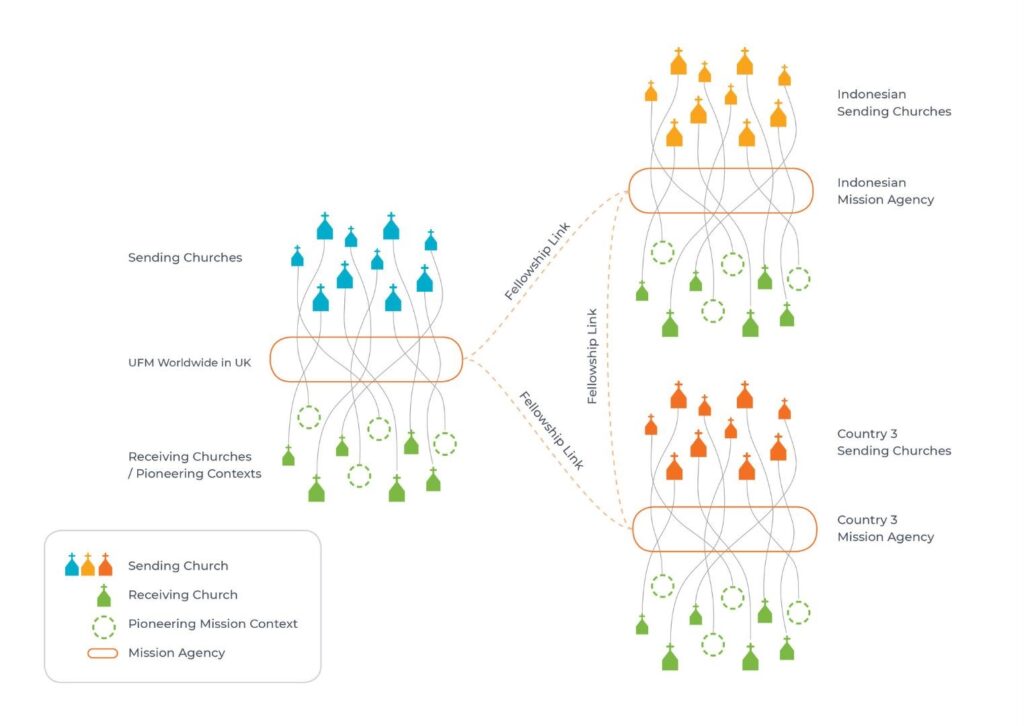

UFM is pursuing what might be called a relational, rather than structural, answer to that question. The model below shows a network or fellowship of mission sending organizations and churches that voluntarily associate together.[13]

Together with the partners already mentioned in Brazil and Côte d’Ivoire, we are aiming to collaborate in a mutual way with other mission sending groups we have relationships with within the Democratic Republic of Congo, Indonesia, and Singapore.

Might there be an alternative to large multinational mission agency structures? Something that retains the benefits of international relationships but keeps decision-making and appropriate mission sending models truly in the hands of those on the ground.

Within the network, each partner group is:

- Locally led, not reporting to an international leadership.

- Free to pursue mission sending models most appropriate to their context.

- Independent of one another, with no group having executive authority over another.

As an organization we want to encourage and support emerging mission sending groups, whilst learning from the new models that God will lay on their hearts. This might look like:

- Sharing insights from UFM’s history of supporting cross-cultural workers, with national leaders grounding and applying these principles in their own context.

- Assisting in the training of mission agency leaders and church leaders, specifically as it relates to mission sending.

- Offering some financial partnership, with ‘no strings attached’, for example seed funding to see a new locally-led mission agency established.

- Inviting partner leaders to share at UFM conferences.

- Facilitating Majority World mission partners coming to serve in Europe.

The model will work best if there is a true polycentrism to the fellowship, with learning shared in each direction between each constituent group.[14] Before establishing too clearly how this network might operate, we plan in 2025 to have the first in person gathering of such a group to hear the insights, suggestions, and hopes of all the partners.

Conclusion: Taking the next step

We began with the words of three Indonesian mission agency leaders, ‘We want to work with you, not for you.’

As you reflect on all the Lord is doing in raising up workers from across his world church, here are some questions to help you take the next step in encouraging a greater sense of mutuality in mission sending today.

If you are involved in an international mission organization:

- Are there structures in your organization that could be closed or repurposed to facilitate the mission service of others?

- Do you have historic relationships with national churches that need to be refreshed to promote partnership, not paternalism?

If you are sending from the Majority World:

- Consider what mission sending models you would want to pursue if you could start with a blank sheet of paper. What could international organizations learn from this?

- What barriers are presented to your sending ministry by the well-meaning structures of international organizations? How can you best communicate these with those groups?

Endnotes

- Michael Prest, ‘The West with the Rest? Exploring the Role of UFM Worldwide in the Sending of Overseas Cross-Cultural Missionaries from the Indonesian Church’ (MTh diss., University of Glasgow, 2022), 204–205.

- Warren W. Webster, ‘The Nature of the Church and Unity in Mission,’ in New Horizons in World Missions, ed. David J. Hesselgrave (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1979), 247.

- Stan Nussbaum, A Readers’ Guide to Transforming Mission (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2005), 120.

- See, eg Steve (Heung Chan) Kim, ‘A Newer Missions Paradigm and the Growth of Missions from the Majority World,’ in Missions from the Majority World: Progress, Challenges and Case Studies, ed. Enoch Wan and Michael Pocock (Pasadena: William Carey Library, 2009), 14.

- Marty Shaw, Jr., ‘The Future of Kingdom Work in a Globalizing World,’ accessed 27 April 2024, https://www.lausanne.org/content/lop/globalization-gospel-rethinking-mission-contemporary-world-lop-30.

- Kang-San Tan, ‘Western Dominance in World Mission: A Time for Change? A Response from an Asian Perspective,’ CMF Thinking Mission Forum, 25 May 2011, accessed 14 April 2024, https://www.academia.edu/1988925/The_modern_missionary_movement_an_era_of_Western_dominance_Was_it_all_bad_and_where_do_we_go_from_here.

- Tan, ‘Western Dominance.’

- Missão Cristã Evangélica do Brasil, the ‘Evangelical Christian Mission of Brazil’ was a partnership formed in 1967 between UFM Worldwide from the UK, Crossworld from the USA, and SAM-Global from Switzerland.

- Alianças das Igrejas Cristãs Evanélicas do Brasil, the ‘Alliance of Evangelical Christian Churches in Brazil.’

- Editor’s Note: See ‘Are Foreigners Still Needed in the Age of Indigenous Mission?’ by Kirst Rievan in Lausanne Global Analysis, July 2021, https://lausanne.org/global-analysis/are-foreigners-still-needed-in-the-age-of-indigenous-mission.

- Union des Eglises Evangéliques Services et Oeuvres de Côte d’Ivoire, the Union of Evangelical Churches, Works and Services of Ivory Coast.

- Name changed for sensitivity reasons.

- Prest, ‘The West with the Rest?’ 208.

- Editor’s Note: See ‘Polycentrism as the New Leadership Paradigm’ by Joseph W. Handley in Lausanne Global Analysis, May 2021, https://lausanne.org/global-analysis/polycentrism-as-the-new-leadership-paradigm.