Editor's Note

This position paper was prepared by the Diaspora Issue Network of the Lausanne Movement. The principal author is Dr Sam George (India/USA) and was written in August 2023. This paper was developed with inputs from the executive team of the Global Diaspora Network, composed of Dr T.V. Thomas (Malaysia/Canada), Dr Bulus Galadima (Nigeria/USA), Rev Barnabas Moon (South Korea), Rev Art Medina (the Philippines), Dr Paul Sydnor(France), Rev Joel Wright(Brazil/USA), Dr Elizabeth Mburu (Kenya), Dr Hannah Hyun (Australia/South Korea), Dr Jeanne Wu (Taiwan/USA), Dr John Park (South Korea/USA), and Dr Godfrey Harold (South Africa).

Introduction

Since the dawn of civilization, human beings have been on the move. Some people move in search of greener pastures, to find livelihood, to seek safety, for education, in search of employment, join family, for trade, to engage in business, or for sheer survival. Others move to escape from conflict, wars, violence, or persecution. Still others move because of adverse living conditions resulting from socioeconomic disruptions, natural disasters, or political upheavals. Some relocate from their rural surroundings to nearby cities, while others travel across the country, and yet others cross many oceans to the ends of the world. Human migration is a major global reality today and everyone is impacted by its far-reaching repercussions. As the flow of ideas, information, products, and money across borders accelerates, so will the flow of people and the many wide-ranging consequences arising out of it.

Human movements have emerged as one of the defining issues of our times as more people now live in a place other than where they were born than at any time in recorded history. The urge, scale, volume, speed, and direction of human migration have escalated to record levels over recent decades. This issue lies at the crux of the massive changes taking place in our societies, economies, nations, and the world. This massive movement of people is fundamentally altering the world order as we have known it resulting in many new realities and almost transforming everything around us. Despite the global pandemic, during which migratory surge was briefly contained due to travel restrictions, the human movement has now bounced back to record levels and there are no signs of it abating anytime soon.

As we approach the end of the first quarter of the twenty-first century, the people on the move worldwide have accelerated to unprecedented levels. Human migration has become so pervasive since 2000 that the United Nations has designated December 18 of every year as ‘International Migrants Day’ and declared 2015 as ‘The Year of the Migrant.’ Migration turns out favorably for many while for others it does not and some perish trying to get elsewhere. An assortment of push factors such as unemployment, drought, famine, conflict, war, religious persecution, ethnic cleansing, lack of security, etc., or pull factors such as educational aspirations, employment prospects, superior working conditions, business potentials, marriage, adoption, etc. has changed the dwelling places for millions each year. The forces of globalization, new technologies of communication, affordable transportation, and the flow of money, material, data, etc. have shrunk our global consciousness and intensified life on the planet.

This position paper elucidates various terms used to describe the movement of people in the world and how it relates to the historic Christian faith and the mission of God. A wide array of terms is used to describe people movements such as migrants, diasporas, refugees, international students, guest workers, expatriates/expats, transnationals, hybrids, internationals, exiles, aliens, nomads, asylees, stateless peoples, deportees, returnees, etc. Other terms used include uprooted, displaced, dispersed, scattered, deterritorialized, undocumented, trafficked, population transfers, etc. The reality of large-scale and long-distance movement of people gets further complicated by conditions, forms, locales, and causative factors linked to human displacements. For instance, internal vs. international, domestic vs. foreign, economic vs. ecological, voluntary vs. involuntary, forced vs. volitional, individual vs. family, irregular vs. illegal, temporary vs. semi-permanent vs. permanent, seasonal vs. circular, the West to the Rest vs. the Rest to the West, etc. This sweeping verbiage in English is a cause of concern for misunderstandings, overlapping usages, dissolution of meaning, and translation difficulties, and could result in much confusion.

The goal of this paper is to develop a comprehensive understanding of the contemporary issue of the movement of people and awaken the global church to understand the diasporic nature of the Christian faith and missional opportunities arising out of the large-scale human displacements. It hopes to help Christians grasp how the dispersed are transforming and advancing Christianity and to mobilize and resource the global church to engage and leverage diaspora communities worldwide. It provides a missiological framework for diaspora missions, a theological foundation for those who seek to formulate Christian doctrines of ‘God on the Move’ and formulate missions among and of the dispersed communities and their descendants globally.

History of Christian mission and the people on the move

It was at the Cape Town Congress of the Lausanne Movement in South Africa in 2010 that the People on the Move was introduced as a strategic mission focus area before the global church and since then this issue has gained significant traction among Christians globally. The Cape Town Congress offered a plenary session and two multiplex gatherings on diaspora missions. A forty-page primer booklet titled Scatted to Gather: Embracing the Global Trends of Diaspora was given out to all participants of the Congress. The Cape Town Commitment (Part II, Section C5) included a statement on diaspora mission describing diaspora to mean ‘people who have relocated from their land of birth for whatever reason’ and called the church and mission leaders ‘to recognize and respond to the missional opportunities presented by global migration and diaspora communities.’ The ever-increasing global reality of migration, refugees, international students, travel, and communication has catapulted this issue to the forefront of the conversation among churches, mission agencies, theological educators, mission thinkers, practitioners, mobilizers, funders, and lay Christians at large.

At the end of the Lausanne III Congress in Cape Town, South Africa, the core group of diaspora mission leaders came together to establish the Global Diaspora Network (GDN) with the aim to expand and deepen the diaspora agenda further globally by catalyzing churches, mission agencies, and theological institutions. GDN is committed to fulfilling ‘God’s redemptive mission for the people on the move.’ It was incorporated as a legal entity in Manila, the Philippines as a charitable organization in 2012 with Executive Team members based in different regions of the world.[1]

GDN convened a Global Diaspora Forum in Manila, the Philippines from 24-28 March 2015, with over 350 leading mission scholars, ministry practitioners, denominational leaders, government officials, NGO representatives, and others from over 80 countries. The fruit of this forum is the compilation of the Compendium on Diaspora Missiology, Scattered and Gathered, published by Regnum (UK) in 2017. Subsequently, GDN with a new Executive Team and two newly appointed Lausanne Movement Catalysts for Diasporas has convened several global and regional diaspora consultations every year in every major region of the world. Furthermore, GDN provided advisory input to numerous mission organizations and theological institutions in regard to diaspora mission studies and research. The Scattered to Gather booklet[2] was revised in 2017 and translated into several languages such as Korean, Mandarin, Japanese, Spanish, and Portuguese and made available as an Amazon Kindle e-book, while the compendium[3] was revised and republished in2020 by Langham Publishers for wider circulation.

The emergence of diaspora mission focus has a much longer history. The early migrant Christians especially from Asia and Africa attended local churches in host countries and as their number grew, they established ethnic and immigrant churches in those countries. The preference for language-specific worship, distinctive cultural and spiritual practices of migrants, the challenge of raising their foreign-born children, their inability to fit into host nation churches, and their institutional links to their native lands necessitated the creation of migrant churches wherever they lived. The leaders of these newly established migrant churches often maintained denominational ties with churches and leadership structures in their respective homelands for organizational support and guidance. In return, these migrant churches supported homeland churches and mission projects through remittances. In the process, the continuous flow and cross-pollination of ideas and spirituality across geographies and time zones galvanized the growth of migrant churches. This phenomenon also positively contributed to families and communities back home socio-economically.

In the sovereignty of God, ethnic diaspora networks started emerging: the Chinese Co-ordination Committee of World Evangelization (CCCOWE) in 1976, the Filipino International Network (FIN) in 1994, the International Network of South Asian Diaspora Leaders (INSADL) in 1996, the Korea Diaspora Network (KDN) in 2004, etc. Each of them hosted meetings and consultations which resulted in newsletters and the development of resources for enhancing diaspora ministries. These emerging diaspora networks generated many conversations with different national and global ecclesiastical structures. Among the evangelicals, one of the earliest formal deliberations on the topic of the People on the Move transpired at the Lausanne Pattaya Mission Consultation in 2004 which resulted in the release of the earliest position paper titled ‘The New People Next Door’ (LOP 55). It offered an impetus for heightened engagement on the issue of global migration and sounded the clarion call for diaspora missions at several Christian conferences, mission think tanks, and theological institutions. All of these provided the essential ingredients for the development of the diaspora mission as an issue network within the Lausanne Movement in 2007.

The Lausanne Movement and Global Diaspora Network (GDN) believe God is sovereign over human dispersion and the new reality of migration worldwide can accelerate the mission of God globally. The global church stands at an exciting Kairos moment of opportunity and challenge. GDN envisions catalyzing the global Church to embrace and expedite ministry among the People on the Move. It is committed to mobilizing local congregations, mission agencies, ministry networks, institutions, and other organizations to engage in cross-cultural global missions in their neighborhoods everywhere. It aims to capitalize on transnational linkages and the connection of diaspora communities for a multipronged kingdom impact globally. It hopes to facilitate churches everywhere to realize their diasporic origin and understand the faith transformation across generations. The Christian migrants have established vibrant immigrant congregations in their places of settlements and have become a potent missionary force to revive Christianity where it is now declining while diversifying the appearance of the Christian faith. It remains dedicated to awakening and alerting Christians from everywhere now living everywhere to be discipled and serve the greater Kingdom purposes of the earthly dispersions and prepare the global church to an eschatological reality of ‘a great multitude that no one could number, from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and languages, standing before the throne and before the Lamb’ (Rev 7:9).

Terminologies: Divergent and overlapping

Many different terms and expressions are used to describe the People on the Move. Numerous scholars, strategists, and practitioners use them synonymously and interchangeably without realizing the nuances associated with each of these terms. Some prefer one over the other while others naively consider it all the same. Certain regions of the world and languages favor some terms or treat them as the same, unaware of many subtleties associated with each of these terms. The Bible uses a variety of terms to describe the notion of human displacement and theological literature further broadens the meanings, contexts, and connections to the Christian mission through the ages.

Each term provides a very distinct meaning to this growing global reality and maintains a particular rationale focus and thrust.[4] When investigating the Bible, other historical literature, social sciences, national laws, related economics, contemporary policy matters, or missionary activities of the church, etc. it is common to lean in one direction or the other. The preference for some terms among certain academic specialties has further complicated the usage of these varied terms. For example, history and legal studies prefer ‘migration’, and social sciences and literary studies favor ‘diaspora’ while humanitarian workers and policymakers are increasingly using ‘displaced’ as the preferred term. Some apply the term diaspora exclusively to the original Jewish exilic contexts, while others use the term to include all displaced people even in our present contexts.

No one term would be solely sufficient to capture the multifaceted complexities associated with the contemporary large-scale human movements around the world and we must draw insights from diverse disciplines, geographies, scholars, and literature to enrich our understanding of this phenomena. The movements can range from short distances of repeated movements to long distances over large expanses for permanent resettlements in entirely different societies on the other end of the world. These terms themselves crisscross their definitional boundaries as they are moving terms because they traverse, transcend, and transform their borders in myriad ways. It is wiser to refrain from projecting any one term as the overarching and all-inclusive term to describe this multidimensional phenomenon. It risks the exclusion of other forms of displacements and nuances associated with these terms. Here are brief descriptions of some of the leading terms and a few arguments in their favor and nuances associated with its common usages:

Migration

The root word for migration comes from the Latin migrare, meaning to leave one place and wander to another. Some of the related words include migrate, migrant, migration, migratory, migrator, migrative, migratable, migrator, emigrant, immigrant, émigré, emigree, etc. The UN agency, International Organization for Migration (IOM), defines a migrant as: ‘any person who is moving or has moved across an international border or within a State away from his/her habitual place of residence, regardless of (1) the person’s legal status; (2) whether the movement is voluntary or involuntary; (3) what the causes for the movement are; or (4) what the length of the stay is.’[5]

This is a broad term that encompasses different forms of human displacement irrespective of status, cause, motivation, or duration. Migration results in a change of environment or milieu of dwelling place arising out of human aspiration, opportunity (or lack of it), in pursuit of safety, or running away from danger. Additionally, migration is used to describe the movement of birds, animals, and insects that relocate seasonally from place to place foraging for food. The technology industries are known for many forms of hardware, software, or platform migrations while chemistry and nuclear physics use atomic migration and movement of subatomic particles.

However, the concept of migration remains linear—with a particular focus either on origination (emigrant) or on destination (immigrant) and remains the preferred lens for legal, demographic, and policy studies. More importantly, the migration lens is monogenerational as the descendants of migrants do not consider themselves as migrants, yet they are different from the dominant natives in their places of birth. Migration also fails to see transformation wrought over many decades and lifespans, as well as the manifold transnational linkages, cross-cultural diffusion, and transcultural hybridizations.

Diaspora

A Greek word (διασπορά) meaning dispersed or scattered found in the Old Testament translation of the Bible into Greek (Septuagint) and a few times in the New Testament. Originally it referred to the Jews who were banished to live in exile in a foreign land. They suffered from the trauma of displacement and lived with a deep longing for their homeland. Diaspora is a major theme in the redemptive mission of God in the Bible and Christian history.

Diaspora is a collective term employed along the lines of an ethnic, national, or linguistic group of people that are marked by displacement of some kind while migrants primarily are those who have crossed a border or experienced an uprooting of their native land under varying conditions. Diaspora refers to migrants and their descendants whose identity and sense of belonging, either real or symbolic, have been shaped by their experience of dislocation, mixing, or perceptions. They maintain links with their ancestral homelands and others based in their adopted homelands and elsewhere on a shared sense of history, identity, community, and lived experiences in a foreign country. At times, diaspora studies are considered an offshoot of postcolonial studies with a shared interest in questions of political and epistemic domination, subalternity, race, gender, language, and identity.

Migration is a linear and one-directional term that fails to capture the contemporary reality and complexity associated with the multi-directional, multi-modal, and multilateral ebb and flow of people from everywhere to everywhere. Migration is individually framed and more suitable at the port of entry, law enforcement, or policies governing the migrants. In many cases, whole groups of people are not able to access citizenship despite being born and raised in a country. Diaspora, on the other hand, is a more overarching concept of a complex web of relationships and a collective whole arising out of displacement of some kind and their intermingling that are marked with multiple originations, transit locations, destinations, modes, conditions, and generations. Diaspora includes children of migrants born and reared in foreign lands whereas migrants refer exclusively to the first-generation who have gone from one place to another.

Displaced

While this is a generic term, it is commonly used for Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) which denotes migrants within a country who have moved on conditions of natural calamity, political oppression, ecological crisis, religious persecution, or mere survival. Under the broad category of forcibly displaced people, UNHCR includes Asylum Seekers, Refugees, and Stateless Persons.

IOM defines IDPs as Persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognized geopolitical border. IDPs emphasize the involuntary basis of displacement and external conditions as a chief causative factor for the move. The push factors must be strong enough to overcome every internal hesitancy and circumstantial hurdles to remain in the same place.

The term ‘displaced’ can be more broadly employed to include across a national border in which case it becomes cross-border displacement, most of which occurs across a particular geographical region and a porous boundary under some very dire circumstances. Meanwhile, some writing extends beyond causative factors for this geospatial category of displacement to include all socioeconomic, cultural, and psychological displacements that may be otherwise termed internal migrants. Internal migration does not require passport or visa documents for their movement from one place to another, yet other forms of personal identity are critical as people relocate to nearby cities or another state/province. A term closely associated with displaced is mobility which explains upward mobility from within a particular economic class or outside of a particular caste or social group.

Refugees

The United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), the global refugee agency, was established after the aftermath of the Second World War to help millions who were forced to flee their homes. The 1951 UN Refugee Convention defines refugee as someone who has fled his or her country ‘owing to well-founded fears of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of their nationality and is unable or owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail of the protection of that country; or who not having nationality and being outside the country of their former habitual residence, is unable or owing to such fear is unwilling to return to it.’[6] Most refugees stay in camps close to their countries of origin until the situation in their home countries changes or until they are resettled in another country. As of 2022, around 41 percent of global refugees are children below the age of 18.

Asylum Seekers

A grant of protection by a State on its territory to persons from another State who are fleeing persecution or danger. Asylum encompasses diverse elements such as non-refoulement, permission to remain on the territory of the asylum country, and humane standards of treatment. An asylum seeker is an individual who seeks international protection in another country and arrives in another country asking to be recognized as a refugee. Not every asylum seeker will be recognized as a refugee, but every refugee is initially an asylum seeker. Most refugees and asylum seekers move primarily on account of non-economic reasons, either prevented or not willing to go back to their country of origin because of a threat to survival due to wars, conflicts, violence, persecution, genocide, famine, drought, natural calamities, etc.

Transnationals

More people belong to two or more societies at the same time, either may possess multiple citizenship or legal access to two or more nations at the same time. They work, do life and family, consume media, and engage in economic and political activities across national borders. With the ease of international travel and greater affordability, the transnational populace is on the rise. Some choose to leave their family behind while others are constrained to do so on account of family, community, and religious commitments. Transnational families are those where a member or more of a household live part of a year or for extended periods in another country for work, trade, or business requirements. Transnationalism broadly refers to multiple ties and interactions linking people or institutions across the borders of nation-states. They put down roots in a host country while simultaneously maintaining strong ties with homelands elsewhere. Their identities, belonging, and allegiances cannot be defined easily and are spread across geographical and national boundaries, sometimes conflated and at other times conflicted.

Expatriates

An expatriate or expat is an individual living and/or working in a country other than their country of citizenship, often temporarily and for work reasons. An expatriate can also be an individual who has relinquished citizenship in their home country to become a citizen of another. The move of an expat is considered to be temporary and self-motivated, and there is no intention of a permanent relocation or compulsion to move. The expats are likely to move around from place to place on account of their job requirements or having a global work assignment. The returning expats to their home countries are called repatriates.

Trafficked

Human Trafficking is the recruitment, transportation, transfer harboring, or receipt of people through force, fraud, or deception to exploit them for profit. Men, women, and children of all ages and from all backgrounds can become victims of the crime of trafficking, and it occurs in every region of the world.[7] It involves compelling or coercing a person to provide labor or service, or to engage in commercial sex acts. The traffickers use violence or fraudulent means and fake promises of jobs or education to trick their victims. The coercion can be either subtle or overt, physical, or psychological. The primary modes of trafficking cover bonded/debt labor, involuntary servitude, forced labor, child labor, child soldiers, sex trafficking/tourism, prostitution, exploitation of minors, etc.

Climate Migrants

The movement of a person or groups of persons who, predominantly for reasons of sudden or progressive change in the environment due to climate change, are obliged to leave their habitual place of residence, or choose to do so, either temporarily or permanently, within a State or across an international border.[8] This is an emerging issue and might become even more critical in the coming decades.

As illustrated above, the wide array of terms used to describe the phenomenon of the People on the Move has diffused the meaning of the terms and their usage. A simple definition of ‘any person who changes his or her country of usual residence’ is found insufficient to explain the nuances linked to people movements. Moreover, the study of the movement of people includes students who go abroad for academic pursuits, but does not include short-term displacements such as tourists, and travelers for business, medical treatment, or religious pilgrimages. Interestingly, the Westerners working in the Global South nations are often referred to as expatriates, while those who travel in the opposite direction are called migrants (those from Asia) or refugees (those from Africa and South America). Such nomenclature exposes its innate complexity, duplicity, and power differentials. Some passports have privileged access to other countries through visa exemptions, geoeconomic ties, and diplomatic relationships which may not be the case for people from many other nations. Illegal migration, human smuggling, and undocumented border crossing are difficult to keep track of, not to mention the many risks of treacherous journeys across seas and unsafe routes that are extremely problematic to research and document.

Lately, the term ‘diaspora’ has emerged to include many forms of human displacement within a geopolitical entity and across diverse disciplines, varied conditions, and sundry motives, though a few still prefer its usage strictly according to the original intent of forcibly displaced Jews in historic context. All migration is the process of moving from one place to another. To migrate is to move, whether from a rural area to a city, from one district or province in a given country to another in that same country, or from one country to another. In short, no single lens can be used exclusively to describe the people on the move. Nowadays diaspora is being applied broadly to all who are displaced and denotes any ‘population which deterritorialized or transnational which has originated in a land other than where it currently resides and whose social, economic, and political networks crosses the borders of nation-states or span the globe.’[9]

World on the move: We are all migrants

The National Geographic August 2019 issue featured a cover story titled ‘A World on the Move’ taking stock of the current prevailing issues such as rising seas, crop failures, wars, etc. that are causing a record level of migration around the world.[10] It is very rare to find people today who live exactly where their ancestors originated from. If we dare to trace back in time–a few years for some and a few generations for others–we will soon realize that none of us are native to the places we call home. We all came from somewhere else, and our future generations will explore places and cultures beyond those familiar to us. Migration is the throughline of the human story, no matter how settled we believe ourselves to be. Whether motivated by curiosity or adventure as much as driven by war or hunger, human beings are fundamentally a migratory kind and sedentary stasis is more of an ephemeral exception in our long collective history.[11]

We are all either migrants or descendants of migrants. The story of some form of displacement is woven deeply into our very being, as it was for our ancestors so will it be for our progeny. Humankind is a migratory species. Modern societies, nations, economies, and politics have evolved from repeated human displacements. People move from the countryside to urban centers or as modes of economic activities evolve with the hopes of a better life. Means of livelihoods change with each generation and sociopolitical structures adjust to new realities. The vagaries of economic fluctuations, uneven distribution of capital, opportunity, and infrastructure will disperse people disproportionately across geographies. The differentials in knowledge and skills levels as well as limited job prospects in many parts of the world will force people to look beyond their regional or national borders to be gainfully employed in lands far from where they were born or raised. As more jobs can now be done remotely, it is possible to live in one country and work in another while their immediate family lives in yet another. Earnings, purchases, payments, and investments crisscross borders more easily than ever before.

Our moves are fueled by ambitions, dangers, threats, or fears, although for some these dreams turn into nightmares in the process of their pursuits. We move for sheer survival in the face of life-threatening circumstances or for flourishing in lands that tender better prospects. Even after erecting many walls, barriers, and laws restricting migration, the urge to go abroad is stronger than ever and the propensity to take greater risks to explore opportunities in another place persists relentlessly. With the surge in ethnic nationalism and racial othering in chosen settlements, they remain strangely connected to their homelands using new technology tools, even as they feel like a stranger in places where they have pitched their tents and never really arrive at their desired destinations. Despite the many uncertainties and dangers people continue to explore lands far beyond for we are homo migrateur.

The British geographer and demographer Ernest Ravenstein (1834-1913), often referred to as the ‘father of migration studies’ developed a set of then-groundbreaking ‘laws of migration’ between 1885 and 1889, and many of his principles are still relevant. These laws are a) Law of Migration Distance: Most migrants travel relatively short distances, and the volume of migration decreases with increasing distances. b) Law of Migration Direction: Migration generally proceeds in steps, with migrants moving from small towns to larger towns and then to cities. c) Law of Migrant Characteristics: Younger, single, and economically active individuals are more likely to migrate. d) Law of Counter-Migration: Every migration flow generates return migration, or a significant flow of migration occurs in the opposite direction of the primary migration stream. e) Law of Intervening Opportunities: Migrants often settle at the first suitable destination that meets their needs, reducing the likelihood of reaching the primary destination. f) Law of Step Migration: All migration occurs in stages with each step improving living conditions, economic opportunity, and other factors that attract migrants to move again.

However, these insights have been superseded by new theories to include new facets of contemporary people movements and their future generations in foreign lands. Numerous theories have been postulated over the last century about human migration using diverse lenses and fields of inquiry, ranging from demographic, population science, sociology, economics, anthropology, political science, psychology, technology, transportation, legal and media studies. For example, Neoclassical economic theory views migratory displacement as an individual rational decision to maximize their economic gains by relocating from places with low wages and limited economic opportunities to regions with higher wages and better financial prospects. Market theory posits demand and supply in labor markets while network theory emphasizes the role of social networks in influencing migration patterns. Sociocultural dimensions such as language, ethnicity, and religion play a vital role in attracting or repelling migrants to certain places. World System theory suggests migration is a result of the unequal distribution of resources and opportunities among nations in the global capitalist order. New mobility technologies and access to transportation hubs as well as internet and media exposure are found to be determinative in the mass dispersion of humankind across national borders. Others include gravity, osmosis, infrastructure, and development models of migration theories.

What is utmost critical is that the people movements are a multi-faceted phenomenon, and no single theory can fully explain it. A combination of these theories, and other factors such as psychosocial motivations, exposure to potential prospects elsewhere through media, historical insights, technology access, and modern communication and transportation networks are contributory factors in migratory decisions. New policies and restrictions by certain nation-states redirect migratory flows to other locales. The human agency and composite interplay of various factors shaping migration are helpful to better understand the complexities of the reality of diaspora communities around the world. However, a vitally important factor to consider besides these secular theories is the fact of divine sovereignty in where people are born and where they live (Acts 17:26). God plays an essential role in guiding or determining the dispersal and movement of human beings across the world as well as the formation of many diaspora communities across places and generations that have shaped the destiny of nations and our world.

Table 1: The push and pull forces of people on the move

| PULL | PUSH | |

| Economic factors | Economic opportunities, better job prospects, higher wages, fertile land, and water | Economic hardship, poverty, unemployment, lack of jobs, and crop failure |

| Education and Health factors | Access to quality education, higher education, and quality healthcare | Lack of access to education and healthcare |

| Lifestyle factors | Superior living conditions, better infrastructure, technological advancements, and quality of life | Lack of development, crime, and corruption |

| Political factors | Political stability and a safe environment | Conflict, war, and political instability |

| Religious factors | Religious and cultural freedom | Discrimination and persecution based on religion, ethnicity, and minorities |

| Climate factors | Better climate and natural amenities | Natural disasters, climate change, pollution, limited resources, or resource depletion |

| Relational factors | Family reunification, support needs, adoption, international marriages | Lack of family support, family members in a better place, intermarriages |

Some of the characteristic features of diasporas[12] are, a) dispersal from an original homeland, at times traumatically to two or more foreign regions; b) alternatively, the expansion from a homeland in search of work, in pursuit of trade, or to further colonial ambitions; c) a collective memory and myth about the homeland, including its location history, and achievements; d) an idealization of the putative ancestral home and a collective commitment to its maintenance, safety, restoration, and prosperity, even to its creation; e) the development of return movement that gains collective approbation; f) a strong ethnic group consciousness sustained over a long time and based on a sense of distinctiveness, a common history, and the belief in a common fate; g) a troubled relationship with host societies, suggesting a lack of acceptance at the least or the possibility that another calamity befall the group; h) a sense of empathy and solidarity with co-ethnic members in other countries of settlement; and i) a possibility of a distinctive, creative, enriching life in host countries with a tolerance for pluralism. Other scholars have consolidated or expanded the list or reworded some of the above salient attributes of the people on the move.[13]

Political sentiments and national policies swing widely between being in favor of bringing people in or restricting all movements across borders. In some nations, new walls are erected, or new laws are framed to curb migration, while others are forced to open borders on account of their aging population, declining workforce, or lack of skill set. Interracial dynamics and socioeconomic rivalries can make some places less attractive and lose global talent to other nations. Some take a very short-term perspective, but the real impact of human movement can be seen over several generations and centuries. Our world is more connected than ever before and the increased levels of interaction of people across borders will hasten human mobility in the coming decades. With the steady surge in bandwidth, ease of Internet access, and dwindling cost of data transfers, more people are going to be interlinked through new tools and platforms. More people will move to more places and more frequently and repeatedly in the coming decades. The global pandemic, wars and conflicts, socioeconomic disparities, persecution, physical dangers, and ecological crises will force millions to explore lands beyond their shores. Longing for a more just and inclusive world many will explore livelihood and security elsewhere. Human capital is unevenly distributed and compensated in different places. Brain drain occurs when human capital is depleted in a specific occupation or economic sector on account of the emigration of skilled workers in the field from one country to another. When migrants return with new knowledge, skills, capital, and professional connections to their country of origin it results in brain gain. In some cases, circular migration occurs when people repeatedly move back and forth between two or more countries.

All migration research and forecasts predict that global human migration will continue to surge in the coming decades, and it will remain a central issue worldwide. The shift to renewable energy, inflationary pressure on national economies, new technologies of mobilities, autonomous vehicles, artificial intelligence, robotics, etc. will generate massive disruptions in our current socioeconomic order and it will not pan out fairly for all people in every nation which in turn will increase outmigration out of many nations. We are at the cusp of a quantum leap in human mobility with flying cars, hyperloop, and supersonic planes. The depopulation of some urban centers, aging nations, and demographic shrinking of some nations will result in massive population shifts. Pandemics, inflation, climate change, wars, etc. will force more people to explore more livable places elsewhere in the world. All of that means more people will move in the next three decades than in the previous three centuries.

Growing numbers: Data and trends

A reliable source of most current data on global migration is hard to come by. The figures used by policymakers, demographers, government statisticians, census data scientists, journalists, nonprofits, and the public at large differ widely depending on their sources, definitions, methodologies, and the purpose of their reports. Another fact that makes this task challenging is that these data are dynamic and ever-changing. Counting migrants of many different kinds in different parts of the world on a regular basis is nearly impossible. Moreover, by the time any migration report is published, it may be considered obsolete, although it does not mean it is unhelpful at all.

The International Organization of Migration (IOM) of the United Nations tracks human migration from every nation and reports figures and trends by publishing a flagship report called the World Migration Report (WMR).[14] Since 2000, WMR was produced once in two years, and it comes out every other December. It provides the latest reliable key data and information on global migration as well as thematic essays on highly topical migration issues. In December 2017, IOM developed a Global Migration Data Analysis Center called Migration Data Portal, which provides the latest data and visualization tools of migrants worldwide which are regularly updated by working across many government agencies and international organizations focused on research on global human migration.[15] They are used widely in migration research, media reporting and policymaking around the world.

The latest World Migration Report is that of WMR 2022 which was published on 1 December 2021. The WMR 2022 estimates that there are 281 million international migrants in the world in 2020 which amounts to 3.6 percent of the global population. Only one in 30 people in the world are migrants and the vast majority of people live in the countries where they were born, though many migrate to other places within their countries. Back in 2010, there were only 220 million international migrants in the world (about 3.2 percent of the world population) while in 2000, there were 173 million international migrants in the world which constituted (about 2.8 percent of the world population). In 1990, there were 152 million (2.9 percent), and in 1980, there were 102 million (2.3 percent), while in 1970 recorded 84 million international migrants in the world. In 2020, around 3900 migrants were reported dead or missing globally which is less than 5900 in 2019, though actual number of casualties will be countless more and will surge year after year.

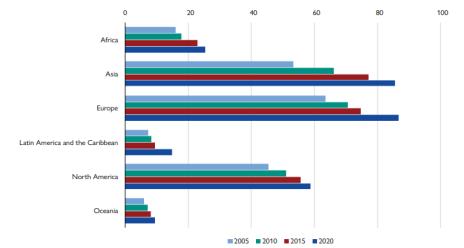

Figure 1: International Migrants by major region of residence 2005-2020 (in millions)

In 2022, women made up 48 percent of international migrants dropping from 49.4 percent in 2000. Of the international migrants in 2022, 14.6 percent were children, and it was 16 percent in 2000. Europe is currently the largest destination for international migrants, with 87 million (30.9 percent of the international migrants) followed closely by Asia with 86 million international migrants living there in 2022. North America is the destination for 59 million international migrants (20.9 percent), followed by Africa with 25 million migrants (9 percent). Over the past 15 years, the number of international migrants in Latin America and the Caribbean has more than doubled from around 7 million to 15 million, making it the region with the highest growth rate of international migrants and the destination for 5.3 percent of all international migrants. Around 9 million international migrants live in Oceania, or about 3.3 percent of all migrants. In 2020, there were 1.8 billion air passengers globally which includes both international and domestic travel and it was down from 4.5 billion in 2019. It also reported 9.8 million people on account of conflict and violence related displacements and 30.7 million due to disaster displacement within the countries globally in 2020.

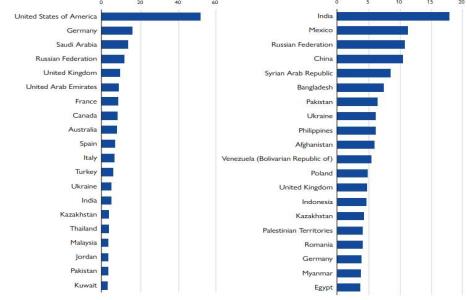

As India became the most populous nation in the world in 2023, it also has the highest emigrant population in the world (18 million). The next most migrant-sending countries are Mexico (11 million), Russia (10.8 million), and China (10 million). The fifth most migrant-originating country is the Syrian Arab Republic with 8 million, mostly as refugees because of the large-scale displacement arising out of war in the region over the last decade. The United States remained the largest migrant destination country in the world over the last 50 years and had 51 million international migrants as of 2022. The next major destination is Germany with nearly 16 million international migrants while Saudi Arabia is the third largest destination country at 13 million. Russia had 12 million and the United Kingdom had 9 million migrants.

Figure 2: Top 20 destinations (left) and origins (right) of international migrants in 2020 (millions)

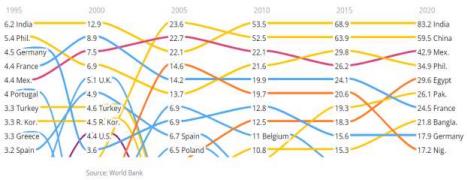

Another principal indicator closely monitored in migration studies is remittances, which is the money sent by international migrants to their families back in their native homelands. Since the turn of the century, this foreign currency revenue stream has become more than the foreign aid or investments received by many countries and a key factor in macroeconomic planning and national policy. Remittances are sent to support family members, provide education, meet familial obligations, savings, start small businesses, do charity projects, getting siblings married, and for religious purposes. As per the WMR 2022 and World Bank report on annual remittances, India continues to be the leading recipient of foreign remittances, topping 83.2 billion USD while China was in second place at 59.5 billion. Both these countries remained on the top of the remittance chart over the last ten years. Other nations among the top five are Mexico (42.9 B), the Philippines (34.9 B), and Egypt (29.6 B). The next five countries are Pakistan, France, Bangladesh, Germany, and Nigeria.

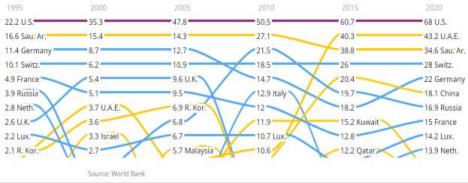

The United States remains undoubtedly the most remittance-sending country in the world over the last twenty five years. Other major remittance-sending nations are the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Switzerland, Germany, China, Russia, France, Luxemburg, and the Netherlands.

Figure 3: Top ten remittance recipients nations (1995-2020)

Figure 4: Top ten remittance source nations (1995-2020)

According to the UNHCR, by the end of 2022, there were 108.4 million people were forcibly displaced in the world as a result of persecution, human rights violation, war, violence or events seriously disturbing public order.[16] This includes refugees, internally displaced persons, asylum seekers, and others in need of international protection. There are 35.3 million refugees and 5.4 million asylum seekers in the world as of 2022. IDPs surged steeply in recent years to reach an all-time high of 62.5 million people in the world in 2022. About 52 percent of the refugees came from three countries namely, the Syrian Arab Republic (19 percent), Ukraine (16 percent), and Afghanistan (16 percent). The major refugee hosting nations are Turkey (3.6 M), Iran (3.4 M), Colombia (2.5 M), Germany (2.1 M), and Pakistan (1.7 M).

The COVID pandemic and the resulting travel restrictions caused a slight decline in migration rates in the past few years around the world, but it has now surged back to pre-pandemic levels. A clear indication of this slump was total air passengers carried dropped by 60 percent in 2020 from a year before. The mobility restrictions created by the created problems for migrants and exacerbated existing vulnerabilities. The national border closure stranded thousands of seasonal workers, temporary residence holders, international students, migrants traveling for medical treatment, seafarers, and others to get to their respective destinations.

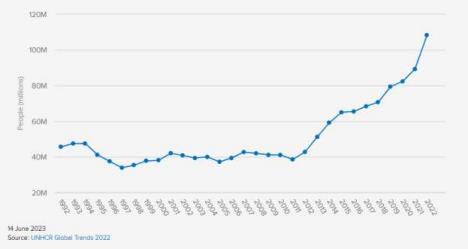

Figure 5: Forcibly displaced people in the world 1992-2023 (in millions)

Moreover, the children of the migrants who were born and raised in the adopted lands of their parents or ancestors may not maintain any active link to places of their origin. While they are a constituent part of an ethnic diaspora in those nations, they are not considered migrants themselves while being perceived so by the majority dominant groups in their domiciled nations. Hence, migration figures are primarily counting the first generation while the diaspora communities are multigenerational and include issues related to the future generation of migrants as well. All people of mixed ancestry and hybridized people may lean in one or another direction depending on perceived benefits and may create a crisis of identity and sense of belonging. Citizenship, level of assimilation, political affiliation, appearance, linguistic competency, educational levels, economic status, integration, and other factors play a determinative role in a person’s network of relationships and self-perception.

All the above figures and explanations fail to portray the scenario of contemporary global migration fully and accurately. The People on the Move is fast changing reality worldwide, and all figures and charts are outdated and do not depict ground realities. All data cited here would be superseded by more current data and readers are advised to visit the cited sources for the latest figures and trends in global migration. This makes the study of migrants and diaspora communities extremely challenging as well as exciting as the number of migrants are ever evolving and all trends are constantly shifting. Finding the religious faith of immigrant communities is still harder to come by. The number of immigrant churches in Western nations are a fast-evolving reality that remains under the radar of host nation Christians and are generally underreported in Christian databases.[17] Since most immigrant churches begin informally at homes or use rented facilities to conduct services in foreign languages with strong ties to their ancestral homelands, it is difficult to precisely assess the proliferation of new migrant churches worldwide.

Bible, diaspora hermeneutics, and Christianity as diasporic

Although contemporary terms such as migration, refugee, displaced, or transnational do not appear in the Bible, the notion of displacement is found across the pages of the entire Bible. The notion of a modern nation-state, geo-political borders, passports, visas, etc. are a recent invention in our planetary existence and should not be mistaken to be absent in the Bible narratives or as irrelevant to salvation history. Contemporary readers are often oblivious to the geographical details of many places mentioned in the Bible, while some of the places have undergone name changes that keep us distant from them. Most readers today are situated far from the original contexts of place and time of the biblical texts that we may claim that all scripture engagements are diasporic at its core.

On the other hand, diaspora is a biblical word and a key theme in redemptive history. It is found in the Greek translation of the Old Testament and there are many occurrences of the term in the New Testament. It is an agricultural term used to describe a farmer sowing seeds over the ground and conventionally referred to the dispersion of Jews during the Babylonian Exile. The term diaspora in LXX has been translated in the English Bible as removed, driven out, scattered, banished, exiled, dispersed, outcast, preserved, remnant, and even horrified. In the New Testament, the term diaspora appears as a noun in John 7:35, James 1:1, 1 Peter 1:1, and as a verb in Acts 8:1, 4, and Acts 11:19.

Nearly all Biblical writings are diasporic, meaning they are written by, to, for, and about migrants and their descendants. They were originally composed, edited, developed, preserved, distributed, interpreted, translated, and read in the context of some form of displacement. Its authors, original readers, and carriers were migrants or their progenies who lived as minorities in foreign lands. Most major characters, narratives, plots, and settings are shaped by displacement of diverse kinds. The need to translate the Hebrew Old Testament Scripture into Greek arose in Alexandria in Egypt among the Jewish diaspora and not in Jerusalem, the center of Judaism at that time. This is because the second and third-generation descendants had lost linguistic competency in Hebrew and had become Greek dominant in the Hellenistic contexts of the Empire. All of the New Testament was written in koine Greek, the lingua franca of the Hellenized peoples which was foreign to Jesus and his disciples. Jewish dispersion, Hellenistic culture, and the Roman Empire played a strategic role in the spread of Christianity in the first few centuries. The contemporary reading and interpretation of the Bible occur far removed from its original readers and contexts. Thus, one may argue that diaspora is a metanarrative of the Bible as it comprises all sorts of migrations under diverse conditions from one place to another. This overarching theme of displacement resonates universally with individuals who are uprooted and seeking a home in a foreign land and is a foundational element of the Biblical narrative. No wonder today migrants everywhere are particularly drawn to its characters and message.

The Bible opens with the expulsion of the first couple out of the Paradise of the Garden of Eden (Gen 3:23), and the wanderings of Cain (Gen 4:12-16). Then we read stories of Noah’s nautical escape from a flood (Gen 6-9) and the mass dispersal of peoples of Babel over the face of the whole earth (Gen 11:8-9). Then, it features the call of Abram to leave his country and people (Gen 12:1-3) and lifelong wandering across the Palestine and Egyptian territories besides a dispute over land resulting in his nephew Lot going in another direction (Gen 13:5-12). Abraham sends his servant to look for a bride for his son Isaac from the house of his family in the old country (Gen 24). A conflict over family inheritance caused Jacob to flee to his ancestral homeland where he got married to his cousins (Gen 27), and later runs away from his father-in-law back to Canaan (Gen 31). Joseph is sold into slavery by his brothers to Midianite merchants who took him to Egypt (Gen 37: 23-28). He rose to occupy the most prominent public office in the most advanced civilization of his time in the world (Gen 41:41-45). Later, when famine broke out in Palestine, the sons of Jacob came to Egypt for grain (Gen 42: 1-2), eventually relocating the entire family to a new country, only to be taken back to Canaan to bury Jacob with his ancestors (Gen 49:29-33). All that in the first book of the Bible and Genesis may as well be called Migrations. Genesis is truly archetypical, featuring all forms of wandering, either punitive or redemptive.[18]

An underlying theme of the second book of the Bible (Exodus) is a colossal movement and the making of a new people escaping bondage in Egypt to be led into a Promised Land flowing with milk and honey. It covers mass escape under cover of darkness, journeying through the desert, being attacked by enemies, crossing the Red Sea, supernatural provisions and protections along the way, seeing God move ahead of them as a pillar of fire and cloud, receiving the Ten Commandments to live by in the new land, etc. – all framed within the context of many forms of displacements. The history of Israel that follows includes cycles of obedience and rebellion (Joshua, Judges), resulting in forced migration to Assyria (2 Kings 17:5-23) and Exile to Babylon (2 Kings 25) as well as divine intervention that brought the return migrants to the homeland (Ezra and Nehemiah). The prophet Jeremiah told the Israelites to seek the welfare of their host nation and care for the foreigners among them (Jer 29: 4-9). The book of Esther recounts the story of Jews living in the Persian Empire, while the book of Daniel provides insights into the experience of Jews living in foreign lands and their efforts to maintain their identity. Jonah is called to preach against the wickedness of Nineveh (modern Iraq) but heads in the opposite direction of Tarshish (modern Spain) only to be redirected back to God’s mission for his life. The prophetic books address the reasons behind the exile and offer hope of restoration, reconciliation, and salvation for the world.

All the major characters of the Old Testament such as Adam, Noah, Abraham, Sarah, Hagar, Isaac, Rebekah, Jacob, Joseph, Moses, Joshua, Ruth, David, Jeremiah, Daniel, Ezekial, Esther, Nehemiah, Ezra, Jonah, and others are presented within the backdrop of displacement of some kind. Bible scholars believe most of the Pentateuch was written by Moses, who was a fourth-generation Hebrew adopted into the Egyptian royal family, grew up and trained in Egypt, struggled with his identity, and married the daughter of a heathen priest in Midian. He wandered most of his life in the wilderness of Sinai and was thereby uniquely qualified to stand before Pharaoh and lead God’s chosen people out of their misery in bondage in Egypt to the Promised Land. The history of Israel – the forming of the nation, its calling to be a light to the nations, its division, eventual forced exile to Babylon, and return are all framed in the context of geo-cultural movements.

Jesus was a man on the move. His incarnation is itself a voluntary displacement from heaven to earth. At birth, he was taken to Egypt by his parents when his life was at risk and many of his generation were killed by the evil King Herod. He was constantly on the move during his earthly life and ministry so much so that it was said, ‘the Son of Man has no place to lay his head.’ (Mt 8:20). The birth of the church, the Acts of the Apostles, and the New Testament letters are all framed in diverse settings of displacements. All of the Bible needs to be grasped in the context of mobility and manifold geographical details to bring out diasporic factors in the making of early Christianity. The mega-theme of displacement is intrinsic to the Biblical narratives as it is all about being away from one’s homeland, searching for belonging, building a community of faith, and being on a mission with God in the world.

The earliest New Testament gospel accounts record that ‘And they went forth and preached everywhere’ (Mark 16:20a). The disciples were also on the move. They were endowed with the power of the Holy Spirit and were commanded to bear ‘witness in Jerusalem, throughout Judea and Samaria, to the ends of the Earth’ (Acts 1:8). At the birth of the church in Jerusalem, the Jewish festival of Passover brought together Jews and converts to Judaism from many diasporic locales such as ‘Parthia, Medes and Elamites, residents of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus, and Asia, Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and parts of Libya near Cyrene, Rome, Cretans, and Arabs’ (Acts 2: 9-11). Upon their return faith communities were established in their hometowns and cities. However, the disciples stayed in Jerusalem on account of growing persecution which in turn caused ‘all except the apostles were scattered [diaspora] throughout Judea and Samaria.’ (Acts 8:1). Later, all ‘those who had been scattered preached the word wherever they went’ (Acts 8:4) and persecution catalyzed the spread of the gospel (Acts 11:19). The expansion of Christianity occurred along the contours of the dispersed Jews across the Mediterranean rim and in the Roman Empire. The entire book of the Acts of the Apostles is replete with geographical details and the significant role diasporas played in the spread of Christianity.

Much of Paul’s letters emerged out of his travels. He was a product of diaspora—a Jew born in Tarsus in Cilicia (Turkey), a Roman citizen, and educated under a leading Jewish scholar in Jerusalem. Hemet Jesus on the road to Damascus, taught at a church in Syrian Antioch which sent him on his missionary journeys, and eventually died for his faith in Rome. Paul ministered to diverse audiences (Jews and Gentiles), cultural adaptations, unity across diversity, a metaphorical reference to a sense of identity and belonging that transcends earthly boundaries, etc. are central to Pauline theology. The examples of people like Barnabas, Timothy, Mark, Luke, Aquila and Priscilla, Silas, Phoebe, Tabitha, Lydia, etc. are all framed within displacements. The letter of Peter is written to diasporic congregations in northern Asia Minor (1 Peter 1:3) and it specifically addresses issues of suffering and hope arising out of Roman imperial rule and persecution. The letter of James is addressed to Jews ‘scattered among the nations’ (James 1:1). It emphasizes that genuine faith should accompany good works, and is particularly relevant in the context of poverty, persecution, and extreme marginalization from oppressive imperial rule. Even the final book of Revelation was written while its author [John] was exiled to the Roman penal colony of the Island of Patmos. Its message encourages the faithful to resist demands of emperor worship and to stand fast even to death, knowing that they will be vindicated when Christ returns, when the wicked will be destroyed and God’s people from everywhere will enter an eternity of glory and blessedness (Rev 7:9). The notion of heavenly citizenship suggests that we are not fully at home in this world but have an identity and allegiance beyond earthly borders (Phil 3:20, 1 Peter 2:11). The theme of symbolic form of journey emphasizes the tension between this world and the ultimate hope of a heavenly home with God’s eternal reign.

The Diaspora lens is essential to grasp the Bible and the missional thrust entwined within. All hermeneutical tasks require a certain distance to read and understand any given biblical text, and the diasporic contexts naturally provide such a space. The displaced people are more cognizant of their situatedness and their alienation in foreign locations. Their struggle with identity and not fully belonging to their adopted homeland yet deeply yearning for the world they left behind make them ideal candidates to engage in the interpretive task. The diasporic displacement allows the dispersed people to approach scriptures in some distinctive manner, and they are particularly attracted to the Bible since its pages are filled with all kinds of migrant narratives. Their lived experience resonates with biblical characters, stories, and dilemmas. They see God’s heart for the aliens and marginalized diasporas and find solace in divine directives to his people to care for the foreigner among them because they were once migrants themselves (Lev 19:34, Deut 10:19).

Diaspora hermeneutics is an interdisciplinary approach to understanding biblical narratives from the vantage point of distinctive experiences and perspectives of diaspora communities that are shaped by histories of migration, displacement, and cultural hybridity. It seeks to interpret the Bible through their lived realities that encompass social, cultural, economic, political, literary, philosophical, and religious contexts that are different from the dominant ones they find at their adopted destinations. It draws from diverse disciplinary lenses and multiple geographical vantage points and cultural contexts to develop new tools and methods for interpreting biblical texts where diaspora communities find many varied accounts of displacement of all kinds and find themselves in these narratives. It expands our static hermeneutical task by bringing fresh dynamism to deepen our understanding of the complex and diverse experiences of the Bible and diaspora communities.

The place of writings of the books of the Bible is not as obvious to most readers in their study of scripture as it is primarily concerned with texts, language, authorship, authenticity, the date of writing, message, and theology of the books. Some recent attempts detailing chronological, archeological, sociological, geographical, and cultural settings of its original texts, author, and readers have greatly enriched our grasp of the message and its missional thrust. Diaspora Hermeneutics advocates an eight-dimensional approach to reading and interpreting the Bible, namely: i) reading the Bible geographically, ii) reading the Bible multi-disciplinarily, iii) reading the Bible communally, iv) reading the Bible intergenerationally, v) reading the Bible inter-ethnically, vi) reading the Bible as hybridized, vii) reading the Bible in multiple languages, and viii) reading the Bible globally. All of these reading strategies entail a basic notion of displacement of some sort as its vantage point and infuse a sense of marginality, multiplicity, mutuality, and missionality into the Biblical narratives.

The Christian faith is diasporic at its core. It is meant to go places which means that the epicenter of the faith always shifts from place to place. The movement of people is of the utmost consequence to Christianity, as migrants and diaspora communities have shaped and reshaped the contours of its growth and spread throughout history. Christian faith moves because Christianity is quintessentially a missionary faith. The ‘indigenizing principle’ makes Christian faith infinitely translatable, and the ‘pilgrim principle’ makes it inevitably transportable. Christian mission concurrently universalizes its particularity and particularizes its universality. Christianity is a deep and wide faith that possesses an innate dynamism within and cannot be bound to any particular place, culture, or people. It enters deep into every culture to redeem it (incarnation) and goes to the Ends of the Earth (mission). It always bursts its boundaries however strong and rigid they may be as it seeks to embrace all. Since the beginning, it has continually diffused across cultural and geographical borders, and many different people in different places have been chief representatives of the Christian faith. Christianity cannot be held captive to any geographical location or domesticated by any people because its nature is to break free of the prisons we enshrine it in. Christianity is a faith on the move, always has been and always will be.

The people on the move and Christian mission

God is sovereign over human history and human dispersion. Apostle Paul in his Areopagus address at Athens during his second missionary journey clearly states:

And He has made from one man from every nation of mankind to live on all the face of the earth, having determined allotted periods and the boundaries of their dwelling place, so that they should seek the Lord, and perhaps feel their way toward Him and find Him. Yet, he is actually not far from each one of us; ‘for in Him we live and move and have our being’; as even some of your own poets have said, ‘For we are indeed His offspring.’ (Acts 17:26-28)

The fact that God creates nations (Gen 25:23; Psalm 86:9-10), God made provision for language and culture (Gen 11:1, 6, 7, 9) and He determines over the spatial (place) and temporal (time) dimensions of our habitation (Act 17:26). All of which serves missional purposes to bring God glory, edification of people and salvation of the lost. The displacement makes people inquisitive of others, question their inherited belief systems, marginalized in new settings, and seek devotion beyond the gods of the land and a savior who is universal beyond territorial deities. The dispersion of people is within the redemptive plan of God for human history. From the perspective of the doctrine of the priesthood of all believers, diasporas are the fulfillment of God’s plan for a worldwide mission that may be called the ‘missionhood of all believers.’ Every nation counts on the presence, participation, and power (either good or bad) of diasporas (short-term, long-term, or those with acquired citizenship). All missionaries are migrants for having to cross national or cultural boundaries. Likewise, all Christian migrants could be considered potential missionaries as they carry out the missionary functions of diffusing the gospel cross-culturally.

Since the creation of the world, migrant displacement and diaspora communities have been indispensable means by which God has accomplished his redemptive purpose through Jesus Christ. The history of the expansion of the Christian faith–past, present, and future– cannot be understood without taking into account the reality of God’s sovereignty, ruling over nations, affairs of humankind, and the moving of his people everywhere. Hence, diaspora is a missional means decreed and blessed by God (Gen 1:28, 9:1, 12:3, 28:14) under His sovereign rule to promote the expansion of His kingdom and the fulfillment of the Great Commission (Mt 24:14, 28:18-20). Human migration plays a vital role in the spread and making of Christianity the world’s largest religion, more than all official missionary activities or imperial projects.[19]

The term diaspora is widely used to describe all people who live in a place other than where they were born. Another associated Greek word is Ecclesia, meaning gathering which is often translated as the church. God scatters people and scattered ones are gathered while the gathered ones are scattered for God’s mission in the world. The scattering and gathering of people are twin corresponding, interrelated, and mutually reinforcing archetypes to understand the mission of God in the world in the twenty-first-century context where mission flow, resources, and influence can arise from anywhere in the world and be directed anywhere else in the world. As we now live in an unprecedented age in the history of Christianity when there are Christians in every country of the world (every geopolitical entity and not necessarily every people group), the gospel has truly reached the ends of the Earth and is bouncing back from the edges to gain new momentum worldwide. The radical reversal in the cultural and demographic composition of the global church is rendering a new face of Christianity and forging new collaborative alliances that will accelerate global missions in the 21st century.

The Diaspora factor forces us to consider Christianity as a universal faith with great diversity within and a healthy sense of mutuality with each other. It accelerates the advance of the gospel and mission work gains new momentum on account of diasporas. It enables the margins to become new centers of Christianity while remaining local everywhere (autochthonous). It imparts a pneumatologically empowered global missiology that unleashes the missional potential of every Christian everywhere together simultaneously to hasten the mission of God in the world. Christian Mission is no more from the West to the Rest, but from everywhere to everywhere. It allows multiple centers of Christianity, and the missionary flow occurs in many different directions; it is truly polycentric and omnidirectional. Everywhere has become a mission field as well as a mission force. The global surge in telecommunication and media arising from growing human mobility is ushering in a new epoch of hyperconnectivity and hypermobility. The issues of climate change and globalization have steadily eroded our geopolitical sensibility and nurtured a global supranational consciousness. The missionary engagement is no longer constrained by financial resources, advanced training, sending structures, or ecclesial affiliations. Anyone anywhere could be involved in bearing witness to Jesus anywhere by migrating and working as a self-supported missionary in other parts of the world and everywhere all the time using new tools and platforms virtually. The developments of new technologies of computing, the Internet, Artificial Intelligence, social media, automation, etc. are ushering in the possibility of metaversal missionary action.

Diaspora missions

The field of diaspora missions seeks to explore the challenges and opportunities of Christian missions among the dispersed peoples of the world, considering their unique cultural, social, and religious contexts. Diaspora Missions are the ways and means of fulfilling the Great Commission by ministering to and through diaspora peoples. Diaspora missiology emerged as a branch of missiology in the 1990s that focused initially on understanding and engaging with diaspora communities in the West. It is described as ‘the integration of migration research and missiological study has resulted in practical diaspora missiology – a new strategy for missions. Diaspora mission is a providential and strategic way to minister to the nations.’[20] It views the strategic opportunity of motivating and mobilizing Christian believers among immigrant communities to evangelize their kinsmen in host countries and their ancestral homelands through their transnational connections.

Diaspora Missiology needs to be differentiated from traditional missiology along four distinctive lines such as its perspective, paradigm, ministry patterns, and ministry style. While the traditional missiology was geographically defined (leading to foreign vs. local or urban vs. rural), diaspora missiology is non-spatial since the unevangelized people cannot be solely defined geographically anymore and they are not bound within any national boundaries or latitudes. It challenged numerous established mission strategies such as the 10/40 window and geopolitical designations. The traditional missiology concentrated on the Old Testament paradigm of come (gentile-proselyte) and the New Testament paradigm of go (Great Commission), while diaspora missiology in contrast focused on the new reality of the 21st century where people are viewed as moving targets and mission as moving with the target audiences. In traditional missiology, the ministry pattern was sending missionaries and providing financial support while diaspora missiology recognizes a new way of doing mission among and with people that is at our doorsteps.

Diaspora mission embraces the growing reality of contemporary mass movement of people which results in an interconnected world and the inevitable formation of diverse and multicultural communities in various countries. Consequently, traditional mission approaches that were primarily centered around sending missionaries to foreign countries, need to also engage with the diaspora populations everywhere effectively. The former mission-sending nations have now become mission fields and some of the migrants from former mission fields are engaged in reaching fellow immigrants and peoples of their host nations. The world is now in our neighborhoods and all Christians need to be awakened to this reality and equipped to reach all people everywhere. Diaspora mission demands the need to contextualize the Christian message and practices to multiple specific sociocultural and religious contexts in multiple locations simultaneously. It requires everyone in every church to bear Spirit-empowered Christian witness to all people every day. It emphasizes the role of Christians in host countries as bridge builders between diaspora communities and the local church by acting as advocates, mediators, and translators to facilitate dialogue and providing help to integrate well into the society while being transformed through relationships.

Table 2: Traditional missions vs. diaspora missions[21]

| AREA | TRADITIONAL | DIASPORA |

| PERSPECTIVE | • geographically divided: foreign vs local, urban vs. rural • geo-political boundary: state/nation to another state/nation • disciplinary compartmentalization: theology of missions, mission strategies | • non-spatial • borderless, no boundary to worry about, transnational, and global • new approach: integrated and interdisciplinary |

| PARADIGM | • OT: missions = gentile-proselyte (coming) • NT: missions = Great Commission (going) • Modern missions: E-1, E-2, E-3 or M-1, M-2, M-3, etc. | • new reality in the 21st century viewing and following God’s way of providentially moving people spatially and spiritually. • moving targets and move with the targets |

| MINISTRY PATTERN | • OT: calling of gentiles to Jehovah (coming) • NT: disciples sent by Jesus in Gospels and by the Holy Spirit in Acts (going) • Modern missions: -sending missionaries and money -sufficiency of mission entity | • new way of doing Christian missions: ‘mission at our doorstep’ • ministry without border • networking and partnership for the Kingdom • borderless church, liquid church, virtual church, etc. |

| MINISTRY STYLE | • cultural-linguistic barriers • ‘people group’ identity • evangelistic scale: reached to unreached • competitive spirit and self-sufficient | • no barrier to worry • mobile, fluid and hyphenated identity • no unreached people • partnership, networking, and synergy |

Furthermore, Diaspora missions often encourages multilingual ministries as most migrants retain their native languages. Since all spiritual matters are often sensed in heart languages, learning foreign languages, teaching dominant language of the host nations, and offering small groups and church services in multiple languages become vitally important. Diaspora missions also recognize, value, and leverage the transnational ties of diaspora communities to have a kingdom impact by building partnerships with families and churches in their ancestral homelands. Also, Diaspora missions involve a holistic approach that addresses the spiritual, social, and practical needs of the diaspora communities in a foreign land by providing social services, language classes, job assistance, and community support besides gospel sharing, especially those displaced under dire circumstances. Overall, diaspora missiology embraces diversity and develops innovative strategies to reach and disciple people from various cultural backgrounds, facilitating the growth of vibrant and inclusive global Christian communities everywhere. The very transnational nature of diaspora communities whose relationships, resources, and influences between nations transcend geopolitical conceptions of missions. It addresses issues of identity, belonging, social cohesion, and intercultural competencies as people navigate their lives in foreign lands while gradually over time and generations assimilating into host realities and maintaining (declining for some) ties with ancestral homelands. It encompasses a global multi-directional view of Christianity where mission occurs from everywhere to everywhere.