Editor's Note

This position paper was prepared by the Diasporas Issue Network of the Lausanne Movement. The primary authors are Paul Sydnor (USA/France), Sam George (India/USA), Jeanne Wu (Taiwan/ USA), and Clene Nyiramahoro (Rwanda/Kenya) and it was written in June 2024. It was developed with many inputs from the executive team of the Global Diaspora Network comprising TV Thomas (Malaysia/Canada), Bulus Galadima (Nigeria/USA), Rev Joel Wright (USA/Brazil), Elizabeth Mburu (Kenya), Hannah Hyun (South Korea/Australia), and John Park (South Korea/USA). Additional review provided by some of the GDN NextGen leaders: Stephen Kim (South Korea/USA), Miho Buchholtz (Japan), Fabiana Braun (Brazil/Germany), Minwoo Heo (South Korea/USA), Suhandy Wei Xuan Yao (Indonesia/Singapore), and Beatriz Tielmann (Brazil/Costa Rica).

Introduction

Human displacement results in the creation of strangers, foreigners, migrants, aliens, exiles, nomads, refugees, and servitude. Faith, hope, and love in the Christian faith are shaped on the anvil of displacement. This paper begins with short descriptions of various terminologies associated with forced displacement and provides a brief historical survey and the current status of forcibly displaced peoples of the world. Then it traces the issue of forced displacements both in the Bible and theological literature. Finally, it presents select themes related to effective ministry among and with forcibly displaced people.

Terminologies

Forced displacement is an involuntary move out of the home country and native community in pursuit of safety and survival. It involves life-threatening force, as well as the accumulated or sudden pressure that compels a person to relocate. There are many different kinds of forcibly displaced people such as internally displaced persons, refugees, asylum seekers, vulnerable persons, undocumented, climate refugees, and others. The conditions to determine the legal status of internally displaced, refugees and asylees are well-defined but others are not. This paper broadly includes all who are forced to move and whose legal status is blurred and needs protection of some sort. Most of them cross various borders under conditions of external or internal coercion where relocation occurs for the sake of sheer survival. Some forced displacements result from a direct and intentional movement while most are passive and unintentional events outside of their control. Although they share many similarities, speaking of only one kind of displaced person can be misleading and often overlook other forms of displacement. The paper uses the term ‘forcibly displaced people’ (hereafter FDP) broadly to refer to a wide range of people and conditions.

FDPs are different from other People on the Move such as migrants, migrant workers, marriage migrants, international students, diaspora communities, and others. The geocultural displacement of these groups is voluntary, whereas FDPs move involuntarily and involve some form of extreme duress. Additionally, countries have laws and legal processes in place to recognize and receive these voluntary migrants. While the Lausanne Occasional Paper (LOP) #70 on the ‘People on the Move’1 addresses broadly the Christian mission in the context of all forms of human movements, this paper specifically focuses on FDPs who are constrained to move for a multitude of reasons and unfavorable circumstances and whose status is blurred but need protection. Some of the FDPs include:

Internally Displaced Persons (IDP)

The term IDP refers to people who have been forced to flee inside their own country due to conflict, wars, natural disasters, or economic collapse. The key distinction of IDP is that they do not cross any national boundary but are forced to relocate from their current habitat to new places within a geopolitical entity. This is one of the largest groups among the FDPs in the world. There are no international laws or regulations about IDPs because technically they are still under the sovereignty and protection of the nation-state even though it may be a failed state or in a war zone. IDPs are included within FDPs because they are displaced under conditions of duress and on account of their lack of resources or connections to seek shelter beyond their national borders. IDPs are vulnerable because there are no governing bodies or laws in their country to grant protection to them. They do not include internal migrants who relocate within their home countries voluntarily for socioeconomic, educational, professional, business, familial, and other reasons.

Refugees

Refugees are different from IDPs because they leave their country and cross an international border to live in a country other than where they were born or have citizenship. When people flee their country of birth owing to well-founded fears of persecution or getting killed, they qualify for protection under the 1951 Geneva Convention and other complementary forms of protection. To qualify as a refugee, the following four conditions of Article 1 in the Geneva Convention are met: a) there has to be a well-founded fear, b) for one of five reasons–race, religion, nationality, member of a particular social group or political opinion, c) are unable to find protection anywhere else, and d) are unable or afraid for their life to return to their home country.2 Those who can document and show they fit this narrow legal definition can receive official refugee status. At times they are referred to as ‘Convention Refugees’ and represent a relatively small portion of those who have been forcibly displaced.

Asylum Seekers

An asylum seeker is an individual who submits a claim in another country for protection or arrives in another country asking to be recognized as a refugee. The term also includes those who are waiting for that state to decide about the claim. Not every asylum seeker will be recognized as a refugee, but every refugee is initially an asylum seeker. Most refugees and asylum seekers move primarily on account of non-economic reasons, either prevented or not willing to go back to their country of origin owing to a threat to survival due to war, conflict, violence, persecution, genocide, natural calamities, etc. An official grant of protection is given by another nation on its territory to persons from another nation who are fleeing persecution or danger. The asylee status encompasses diverse elements such as non-refoulement, permission to remain in an asylum country, and humane standards of treatment.

Vulnerable

Vulnerable Persons referred to in policy documents and legislation include people such as stateless persons, unaccompanied minors, and victims of human trafficking. They are seen as ‘persons of concern’ and have many similarities with FDPs. While lacking any legal status or belonging in their places of habitation, they are highly vulnerable and in need of protection based on universal human dignity and safeguarding from unjust political and socioeconomic laws and practices.

Climate Refugees

When people are forced to leave their homes, communities, or countries because of the effects of climate change, they become climate refugees. They might stay within their home country by relocating to another part of the nation or crossing borders to seek safety and livelihood in another country. They are also called environmental refugees or weather-induced migrants. This is a more recent and growing global reality, resulting from global warming, forest fires, deforestation, desertification, natural disasters, famine, drought, coastal flooding, tsunamis, sinking islands, melting glaciers, erratic weather patterns, earthquakes, volcano eruptions, etc. The increased and repeated occurrences of these conditions are affecting more people with greater fatality and economic impact than ever before. They cause a loss of livelihood and force many to relocate to more habitable places in the world. Though the term climate refugees has been used since 1985, it is considered a super crisis of the 21st century as this condition is slated to force more people to move to new places for sheer survival than all other causes of displacement.

Undocumented

Those who enter countries without official papers, as well as those living unregistered and unauthorized in a country, are called undocumented persons. This is not an official or legal term, however, it encompasses those hoping to register as asylum seekers and those who have failed in their asylum attempts including those fleeing dire economic conditions in their native countries. They are sometimes referred to as ‘irregular’ or ‘illegal’ migrants because of their clandestine travel and unclear status in the host country. They employ unofficial avenues and unauthorized means such as human smugglers. This accounts for why they are referred to as illegals, aliens, or other derogatory terms. There are technically laws in place to allow people to request asylum and protection, and until these cases have been examined according to law, a person is not illegal. The undocumented status reflects the complex processes and mixed motives of these FDPs. A person may begin to move as a refugee but can then be forced to travel without documents and stay under the radar. Likewise, what began as a decision to find a job in another country or seek a better life may turn into a desperate attempt to survive dangerous and life-threatening conditions. The distinctions between regular migrants and undocumented persons are difficult on the surface and differ widely from nation to nation. It primarily rests with legal paperwork, recognition in the host society, work authorization, access to healthcare, and possible pathways toward formal settlement or citizenship.

Other terms

Besides the above subcategories of FDPs, some other people have similar yet very different conditions of forced displacement. They include detainees, deportees, evacuees, illegal aliens, visa overstays, returnees, repatriates, children born to unauthorized immigrants, smuggled or trafficked persons, sexual slaves, bonded slaves, etc. Often all FDPs who flee to find protection elsewhere are viewed as burdens and portrayed pejoratively in the media. They are labeled and treated inhumanely because of the difficulty of defining or grasping their situations. They face discrimination based on their race, gender, religion, or country of origin. They must have the freedom to practice their religion and offer religious education to their children. FDPs are also bound by duties to the country in which they have moved by conforming to its laws and regulations as well as measures taken to maintain public order. As UNHCR cannot enforce its convention stipulations, there are no official bodies to monitor non-compliance and there are no formal mechanisms for individuals to file complaints.

When FDPs do not have legal status, it is easy to stigmatize, label, stereotype, and misunderstand their situation. The people forced to move must be differentiated from other migrant groups who choose to leave their home countries and have specific steps to follow for their relocation and are perceived differently in their host nations. Like all other diaspora communities, their stories of displacement shape their identity struggles, experiences of othering, and raising future generations while maintaining multiple geocultural and linguistic linkages that play a vital role in shaping the global Christianity of the 21st century.

Historical Context

Following the two World Wars, the United Nations General Assembly in 1948 approved the Universal Declaration of Human Rights outlining the fundamental rights of every human being. Among the standards are the rights to equality, liberty, and security including the freedom of movement, the right to seek asylum, and protection from arbitrary arrest or detention. The 1951 Geneva Convention along with its Protocol in 1967 focused on refugees and established an internationally recognized definition of refugees and their protection. The core principle of these agreements is that people cannot be returned against their will to a country where they may face a threat, especially those fleeing conflicts or persecution. Together with additional treaties, these documents gave nations a legal basis to determine refugee status based on humanitarian values to guide a state’s response toward human displacements and provide visa-free travel for holders of refugee travel documents.

In 1969, the African Union Convention expanded the criteria for the protection of refugees by addressing other factors that threaten the well-being of persons. Hospitality was at the root of the African response, yet the massive numbers of displaced in the region make it difficult for individual countries to cope with. Similarly in Latin America, the Cartagena Declaration of 1984 broadened the definition to encompass further circumstances that affect life, liberty, and security. It underlines the plight of IDPs, the right to asylum, the principle of non-refoulement, and the reunification of families. These regional responses highlight the limitations of the Geneva Convention for its narrow, individually focused, and technical definitions. They showcase the complexity of FDPs now characterized as a wide array of displaced people including irregular and undocumented people. As of 2020, 146 member states have ratified the above refugee conventions and obligations spelled out in these documents.

As the world continues to redraw borders and reconstitute governments, the issues related to human displacement have grown considerably. The World Evangelical Alliance called together various Christian organizations and ministries to look at the needs of refugees. They met in 2001 in Izmir, Turkey for a consultation on refugees by asking, ‘What can we all do together that we cannot do alone?’ As a way of helping Christians serving in the forced displacement context, it drafted the ‘Best Practices of Refugee Ministry’, which was later revised in 2015.3 Since then various networks and ministries have developed around the globe, such as the Refugee Highway Partnership (RHP) with regional networks in different continents to promote holistic care, educate the global church to respond to refugee needs, and advocate for refugees.4 To raise ongoing awareness about refugees and ministries among them, RHP in cooperation with WEA has designated a weekend in June every year as World Refugee Sunday and developed various resources for congregations globally.

The Lausanne Committee of World Evangelization (as the Lausanne Movement was then called) held a Global Forum at Pattaya, Thailand in 2004 and developed a position paper titled ‘The New People Next Door’ (LOP #55) on Diaspora Communities and International Students.5 At the same event, another paper focused on refugees—‘At Risk People’ (LOP #34).6 Earlier, another position paper was produced by Lausanne at a mini-consultation held in 1980 and specifically focused on ‘Christian Witness to Refugees’ (LOP #5).7 These documents have played an instrumental role in the development of ministry among refugees worldwide. However, the issue of forcible displacement has grown noticeably over the last two decades and become more complex and global, there was a need to develop a more nuanced position paper based upon an evangelical understanding of displaced peoples of the world. In fact, human migration of all sorts has played a strategic long-term impact on the spread and the making of contemporary Christianity worldwide and will continue to do so in the coming decades and centuries.8

A notable network engaging in the issue of forced displacement is the Global Diaspora Network (GDN)9 which is the official issue network of the Lausanne Movement and had three major areas of focus since its inception in 2010 namely economic migrants, international students, and refugees. It convened major regional and global consultations annually in nearly all major regions of the world and always included various groups of FDPs. GDN was instrumental in developing a wide range of publications using missiological and theological lenses related to global migration and various diaspora communities.10 GDN has brought migrant missions, diaspora missions, and diaspora missiology into the forefront of seminary education and mission training globally and catalytically fueled ministries and leadership training for migrant, refugee, and diaspora communities around the globe. GDN has developed a mobile app called GMove to connect and resource ministry leaders virtually.

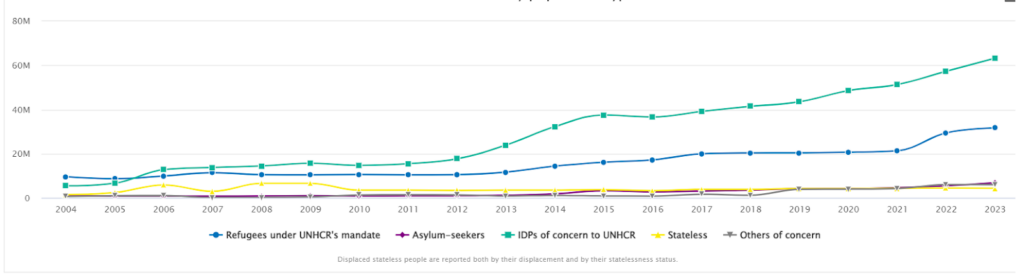

Current Reality

The Cape Town 2010 Congress of the Lausanne Movement identified ‘people on the move’ as a strategic mission focus area for the global church. This was a prophetic call and since then there has been a steady surge in migration and refugees globally. Human displacement has become a world-tier issue—a global challenge that transcends national borders and affects humanity on a large scale—and will impact the mission of God in the coming decades.

In the last ten years or so, millions have been displaced by wars and conflicts in Myanmar, Central Africa, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic, and most recently in Ukraine and Gaza. In addition to these, there are major environmental and weather-related disasters in Pakistan, Bangladesh, India, China, Brazil, Philippines, and Columbia as well as enormous earthquakes in Turkey and Northern Syria. Together these make up the main hotspots of human displacement today. Fires and floods in Australia, North America, and Europe have forced many out of their homes. Islands have sunk or been depopulated entirely in the Pacific and the Caribbean, and Tsunamis in Indian Oceans have threatened millions to relocate to higher grounds or seek shelter overseas. The collapse in the Venezuelan economy has pushed nearly one-fifth of the entire population to go abroad and people continue to leave at an average rate of 2000 per day. Additionally, confusion and uncertainty of displacement have become major political tools along the corridors of human caravans moving into Europe and North America. It must be underscored that top FDP hosting countries are mostly in the Global South and not in Europe or North America.

According to the United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR), at the end of 2023, there were a total of 117.3 million FDPs in the world resulting from IDP (68.3M), refugees (37.6M), asylees (6.9M), stateless people (4.4M in 95 countries), and people needing international protection (5.8M). About 40 percent (47M) of the FDPs are children below the age of 18 and in the last five years, 3M children were born as refugees. Seventy-three percent of refugees come from just five countries: Afghanistan (6.4M), Syria (6.4M), Venezuela (6.1M), Ukraine (6M), and South Sudan (2.3M). Most of the FDPs were hosted in nearby countries such as Iran (3.8M), Turkiye (3.3M), Colombia (2.9M), Germany (2.6M), and Pakistan (2M).

UNHCR identifies three possible solutions for FDPs: a) return to their home country, b) resettle to a third country, or c) remain and become naturalized in the host country. Very few people find one of these solutions. In 2023, only a fraction of a percent of refugees could be resettled in a new country. The vast majority—75 percent of FDP—are hosted by poor or middle-income countries and the least developed nations hosted 21 percent of the FDPs in 2023. 1.2 million refugees returned to their country of origin and 158,700 were resettled in other nations in 2023.11

For many people, images of the forcibly displaced bring to mind people who are desperate, hopeless, illegitimate, helpless, uncivilized and uncultured, and even undeserving, and violent. These images depict FDPs as individuals dependent on others, who cannot make decisions for themselves, and who take away valuable resources from their host communities. It wrongly suggests that FDPs are incapable and need other’s favor and assistance. These are myths and lies that are far from the truth. FDPs themselves know that their dreams have been shattered and have lost all sense of belonging. The lingering question in their mind is, ‘Where is home? How will I make it through this day?’ They have lost their voice and are at the mercy of humanitarian agencies, who may carry various assumptions about them. These organizations consider themselves experts on the FDPs but may even propagate the myths about them.

As a result, millions of FDPs are wasting away in refugee camps worldwide. Whether resettled or living in refugee camps, FDPs have one thing in common: complex trauma and hopelessness. If we do not help them deal with it safely, our efforts will bear no fruit, and we will feel discouraged, exhausted, and traumatized. Any durable solutions are hard to come by. While the number of FDPs who found a solution has increased in the first half of 2023 in comparison to the same period last year, the global church can and must engage this growing crisis though it may appear any lasting solutions are nearly impossible to achieve.

A Roadmap of the Future

The ministry among FDPs requires a map to help everyone find their way through difficult and life-threatening situations. The Scriptures surely provide the compass for orienting the map. However, with each new generation and era of displacement, the roadmap needs to be redrawn with new and old landmarks along the way. Some of the landmarks on the map of displacement include places of loss, restoration, sense of belonging, exilic sensibility, people as friends and strangers, or cultures of ethnicity and egocentricity. The degree to which we claim any of these landmarks signals the extent to which we struggle to understand or are willing to receive FDPs.

Often church lags in understanding the issues and needs of people affected by forced displacements. The default in the face of change or any new thing is to continue with the same approaches as before. This might mean welcoming new neighbors from another culture or developing new theological foundations and ministry approaches in our local churches. The ministry among displaced people needs a mission approach that is appropriate for meeting new people with different needs and challenges. We must become active listeners and learn to contextualize ministry for their unique situations. We need to adopt a Christ-like outlook who came as a humble servant. Even some of those who are coming to the Global North are coming from places in the Global South where Christianity has grown in recent years and is bringing fresh fires of revival to places where the faith is declining now.

Refugees are travelers on the way, and they are also potential vehicles and ambassadors of God’s message. Storms and dangers are unmarked on their life maps. On this map, churches are like lighthouses that show a way to safety and hope. The church and its people are like oases and sentinels in the desert. They are a source of life for those seeking refuge and they are at the same time in great need themselves of the life and message that God sends through refugees, asylum seekers, and other FDPs on their journeys. The contours and boundaries of these encounters share both the blessings and afflictions that accompany FDPs.

Just as the land is crucial for understanding the Old Testament, so too displacement is crucial for knowing the way God moves in this world and forced displacement raises the stakes. Walter Brueggemann says in the opening page of his treatise on the land in biblical theology: ‘The sense of being lost, displaced and homeless is persuasive in contemporary culture. The yearning to belong somewhere, to have a home, to be in a safe place, is a deep and moving pursuit.’12 Every person along the way needs to read and understand the map of displacement. The church therefore cannot understand this map like they would in some other context, and often, they will need to read this map repeatedly to realize what God is doing in the world.

One concern of this paper is for churches and Christians to consider their role among displaced people on the move. The policies and strategies in place to bring assistance can also promote a negative image of displaced people as they are portrayed as dependent on assistance. They refer to the need for burden sharing, giving the impression that displaced people bring a load for others to carry. Certainly, when people are traumatized and deprived of dignity and necessities for life, there are burdens to bear and needs to meet, however, as human beings, their contributions to society bring new perspectives on resilience, hopefulness, innovation, and entrepreneurship that we all do desperately need.

Experiences of Forced Displacement

Reports and stories provide a first-hand account of forced displacement, and the following five categories broadly summarize these experiences. They reflect root causes, and they show the extent and complexity of FDP experiences. On one hand, the experience creates suffering and hardship, but it also shows the creativity and resilience of the person. Most of all the experience of each person in displacement often finds a parallel in Scripture.

Coping with hopelessness

FDPs navigate the daily stress of physical fatigue, financial hardship, educational and job loss, corruption, and lack of viable options. They must find a way out of their many problems and cultural, political, and religious tensions. Every day they face discrimination, persecution, cultural landmines, conflicted beliefs, and a troubled conscience.

A young woman on her way home from school met her friends as they passed by a protest rally. Without any thought, the group posted a photo online of themselves at the rally. Some days later the police began to track down people who were connected to the protest. As the authorities sweep through her neighborhood one evening, her family has no option but to whisk her out the back door and send her out of the country. Suddenly she is alone and afraid for her life without any alternatives or ideas about where to turn or whom to trust. She is like a lost sheep and prays for God to hear her and to send someone to help. She is like Hagar who fled into the desert alone in her impossible situation. Yet God sees her and sends an angel, who finds her by the spring of water and brings healing. Hagar confesses, ‘I have now seen the One who sees me’ (Gen 16:13).

Facing violence and death

FDPs flee war zones, violence, and life-threatening conditions. They live in a no-mans-land of vulnerability and helplessness waiting in limbo perpetually and uncertainty threatens their very existence. Thousands undertake dangerous journeys across deserts and try to cross the vast seas in unworthy vessels only to drown. Countless numbers of people have died or disappeared entirely from the face of the earth. One survivor reported ‘The dangers are not the hard part. We get used to these every day. The hard part is not knowing what to do next.’

This is like Mark 4:35-41 when the disciples were in a storm. They woke Jesus up saying, ‘Don’t you care we are going to die!’ Jesus asked, ‘Why are you so afraid . . . don’t you believe’? This is a relevant story for refugees who face the threat of conflict and death. Many refugees would respond, ‘Yes, Lord, I know you can save my life, but I am still afraid every day.’ God’s people across the world need to hear testimonies like this to know that God’s hope comes amid the storms. God sees those in life-threatening conditions and sends his people as friends like Jonathon who encouraged David in the desert (1 Sam 20:3-16).

Dealing with trauma and shame

It is not possible to understand the experience of forced displacement without addressing trauma and shame. Trauma shows up as complex psycho-social situations of compounded stress, loss of protection, lack of safety and well-being, personal discouragement, dangers, regret, helplessness, fear, disillusionment, and suicidal ideations. Many displaced people end up in places surrounded by walls and fences. These barriers separate them from other communities and stand as a reminder of their isolation and trauma, and often complex, and confusing situations they have passed through. The displaced people live for a long time with dividing walls, like shadows that seem impossible to cross. It is a wall of shame to overcome. Jesus crossed many barriers with the woman at the well in John 4:1-29. Jesus met her at the well when she was alone and isolated. He did not perform a miracle but showed respect. He listened to her questions and gave her the time she needed to build trust and recognize that he was the Messiah. Changed by the encounter she proclaimed in her village, ‘Come see the man who knew everything I ever did!’ In this way, Jesus got past the wall of shame of a displaced marginalized person within her town.

Fighting for dignity

This is a struggle against discrimination and prejudice. FDPs endure mistreatment, arrest, deception, imprisonment, and manipulation. At times, it is dehumanizing and gradually eats away their sense of being. In one situation a man who had lost all his belongings and was left to live in a ditch. When asked he responded, ‘They have kept me out of their land, but no one can keep me from the one who made me.’ Jesus talks about the coming of justice in the kingdom of God saying: ‘I was hungry, and you gave me food; I was naked, and you clothed me; I was a stranger and you welcomed me.’ But his disciples answered, ‘When did we see you like this?’ (Matt 25:31-40). The kingdom of God is a matter of vision. Jesus often calls his followers to have eyes to see. We need to see the face of God in others. This kind of ministry brings hope and the realization that God is at work even before we get there. God sees us, but where and how are we seeing God’s power and presence at work in the world?

Nuancing displacement experiences

The stories of FDPs involve many painful pasts, current predicaments, and uncertain futures. They encompass complex afflictions but highlight positive traits such as mental toughness, emotional resilience, problem-solving, a sense of justice, determination to persevere, and courage to resist. The reality of the displacement experiences is nuanced. A group of FDPs crossing a border will have different reasons for their journey but have a shared common experience. These experiences parallel the effects of sin in the world. It depicts a fallen humanity that has lost its way in God’s creation. The Scriptures trace how God brings grace and redemption into situations of displacement to build a kingdom and a people for himself. Many FDPs have noted that they see themselves in the stories of the Bible. Thus, the experiences of displacement become redemptive when people realize that the purposes of God are at work in and through their earthly displacements. Not only do they make sense of all their displacements, but they see the divine being as a God who is on the move.

Forcibly Displaced People of the Bible

Displacement of some form is found throughout the pages of the Christian Scriptures. It is so pervasive that one may claim that displacement is a mega-theme of the Bible. Its characters, plots, narratives, backdrops, original authors, and readers are all framed within the context of many different kinds of displacements from one geographical place to another. The theme of displacement is significant throughout both the Old and New Testaments, and it is woven deeply into the biblical narratives that it serves as a catalyst for divine revelation and transformation of individuals, families, and nations throughout as a metanarrative. Some of these displacements took place involuntarily or under force within an overarching scheme of oppression, hardship, divine intervention, and eventual redemption. The words of displacement in this section are highlighted in italics.

Here are some notable examples of FDPs in the Old Testament: Adam and Eve were expelled from the Garden of Eden as a divine punishment for their disobedience (Gen 3:23-24). Cain after murdering his brother Abel was condemned to wander the earth leaving him without community, necessities, and security (Gen 4:12-14). As the great flood destroyed the Earth, God instructed Noah to build a giant ship to save his family and a pair of every living creature, essentially forcing them to float over the waters for months (Gen 6-9). At the tower of Babel, humankind is forcibly dispersed all over the face of the Earth (Gen 11:8-9). Abram, with his wife Sarai and nephew Lot, left their native homeland in the Ur of Chaldeans and traveled to an unknown place who lived much of their lives as nomads in foreign lands (Gen 12:1-2). Their Egyptian maidservant Hagar who bore Ishmael to Abram was sent away by her mistress Sarai and later ran away because of household tension and harassment (Gen 16: 6-8). Jacob had to flee to Haran to escape the wrath of his brother Esau (Gen 28:2-5) who later faced a famine in the land and was forced to relocate to Egypt where his descendants became enslaved under a new Pharoah (Gen 46:1-7). Joseph was sold into slavery by his half-brothers to Midianite merchants (Gen 37: 23-28), where he attained a position of honor only to be falsely accused by his master’s wife and thrown into prison (Gen 39: 16-20). The Law and the Prophets emphasized love and hospitality toward foreigners in the Promised Land, ‘The foreigner residing among you must be treated as your native-born. Love them as yourself, for you were foreigners in Egypt.’ (Lev 18:34).

The most significant example is when Israelites were in bondage in Egypt for centuries God sent a deliverer to rescue them in the person of Moses and they wandered through deserts for decades on their way to the Promised Land (Exod 1-5). The laws of the cities of refuge provided asylum to manslayers until they could stand trial and this provision applied to strangers and sojourners in the land (Num 35; Deut 19; Josh 20). When faced with a famine, Naomi was forced to migrate to Moab where she lost her husband and two sons, and later returned to Israel with one of her foreign-born daughters-in-law who became part of the lineage of David and the Messiah (Ruth 4:17). During Israel’s first King Saul’s reign, David was forced to flee and live in hiding in foreign lands and among enemy tribes to escape Saul’s attempts to kill him (1 Sam 21-26). David sang about taking refuge in God when he repeatedly fled from Saul who sought his life out of jealousy and fear (Ps 7:1, 11:1, 16:1, 31:1, 46:1, and others) and the Psalmist remembered, ‘When we were few in number, of little account, and sojourners in it, wandering from nation to nation, from one kingdom to another people…’ (Ps 105:12-14). The Jerusalem Temple was built with the help of aliens (1 Chron 22:1-2) and Solomon took a census of all aliens in the land and assigned them work (2 Chron 2:17-18). The inhabitants of the ten tribes of the Northern Kingdom of Israel were defeated and deported by the Assyrian Empire in 722 BC (2 Kings 17:5-6). Later in 586 BC, the city of Jerusalem and the Temple were destroyed, and the people of Judah were banished to Babylon, where they lived in captivity until the Persian conquest allowed them to return (2 Kings 25:11; Jer 52:28-30). The Exile remains one of the most significant events in Jewish history and profoundly shaped their identity, Scriptures, and theology.

The Prophets of the Old Testament mostly moved around within the nation of Israel like Samuel between Ramah where he lived and judged Israel, and other significant places like Shiloh where the Ark of the Covenant was kept before the temple was built in Jerusalem. While Isaiah’s prophetic ministry was centered in Jerusalem addressing the people of Judah and surrounding nations, Jeremiah faced forced relocation when he was put into a cistern and later taken against his will to Egypt by Judean rebels who fled fearing retribution after the assassination of Gedaliah, a governor appointed by Babylon (Jer 38:6). Ezekial’s ministry occurred while in captivity in Babylon (Ezek 1: 2; Kings 24:10-18). Jonah’s travel is the most dramatic, when God sent him to Ninevah, he went in the opposite direction to Tarshish and was forced to change course through supernatural interventions to make the reluctant prophet lead a citywide revival (Jonah 1-3). All prophetic ministries required them to engage with various tribes, face hostility, and deliver difficult messages mandated by God while navigating the complex geo-cultural and political landscapes of their times.

The theme of forced displacement can be seen in the New Testament as well, especially when we realize the setting of Jesus’ earthly ministry and the early church took place in the backdrop of the Roman Empire. The gospel situates the birth of Jesus in the wake of the Roman decree for a census by Ceaser Augustus which required his parents to visit their hometown of Bethlehem (Luke 2:1-3). Soon after the birth of Jesus, Joseph was warned in a dream to flee to Egypt with Mary and the infant Jesus to escape the royal edict to massacre all infants in Bethlehem. They lived as refugees in this neighboring country until the death of Herod. (Matt 2:13-15). The Gospels present Jesus subtly and overtly challenging the Roman understanding of power and economic structures. The final wrongful conviction and death of Jesus by crucifixion occurred at the hands of the Roman officials. Jesus is portrayed as a harbinger of true and lasting peace, contrary to the promise of the Pax Romana.

All of Jesus’ disciples, except for John, were persecuted and killed for their faith. Those who were scattered preached the word wherever they went (Acts 8:4). One of the ways the gospel spread in the first century was through involuntary scattered believers as is the case of believers in Antioch where they were called Christians for the first time (Acts 11:36). Apostle Peter wrote his letters to displaced minorities living under Roman oppression while he was being held and tried in Rome (1 Pet 1:1). The letter of James is addressed to Jews who were forcibly ‘scattered among the nations’ (James 1:1) Apostle Paul was a product of Jewish diaspora and much of his ministry and writings emerged from his extensive travels which included conflicts, opposition, shipwrecks, arrests, imprisonment, and was eventually killed in Rome. His determination and resilience to spread the gospel came despite formidable opposition and great personal cost. Much of Apostle Paul’s misplaced zeal for the inherited faith and his dramatic encounter with the risen Christ that profoundly shaped his life, ministry, and writings cannot be fully grasped without viewing him as a product of the Jewish diaspora. All of his letters to the newly formed dispersed communities have to be read, interpreted, and understood with diasporic sensibility because the early Christian readers were living under imperial conditions and were persecuted minorities without socioeconomic or political power. The final book of the Revelation was written while its author (John) was forcibly exiled to the Roman penal colony of Patmos and he encouraged forcibly moved readers to resist emperor worship and remain steadfast even unto death, knowing that they will be vindicated when Christ returns (Rev 7:9).

Theological Themes

Displacement is central to the notion of missions and signals the way by which God builds his church. The forced displacement shows the nature of God’s redemption amid suffering and trials. Just as the Scriptures unfold in various dimensions of displacement, they also connect essential aspects of theological doctrines to the notion of displacement. The ‘People on the Move’ argues that Christian doctrines need to be conceived in motile terms. There are numerous themes particularly related to forcibly displaced such as hospitality, shalom, exile, restoration, loving the stranger, remembrance, grief, lament, suffering, and hope. This section of the paper identifies several essential themes of Christian theology that maintain a close connection to displacement, but also argues how the understanding of displacement is rooted in core doctrines of the faith.

Various dimensions of displacement help to develop important theological themes. The Fall and Expulsion from the Garden of Eden establish the core foundations of humanity on the move. The call to journey given to the forefathers such as Abraham develops the role of faith. The Exodus and flight from Egypt introduce covenantal aspects of identity built on awareness of God’s provision in the past, the hopes of a future promise, and their daily struggles in the present. This aptly describes the dilemmas faced by contemporary FDPs.

The account of exile in Babylon and Assyria further describes the precariousness of the life and identity of God’s people needing restoration. The coming of Jesus as a stranger in this world to make redemption possible. Jesus moved from heaven to earth and even lived as a refugee in Egypt briefly. The trajectory of salvation through Jesus offers a model for his disciples to live as strangers and aliens in this world. Whereas Apostle Peter wrestled with the burden of his earlier life and the weight of his displacements in later life, Paul’s life as a diasporic Jew and his ministry were earmarked by constant movements. Like all displaced people, followers of Christ are called to live as aliens in this world with an eschatological vision of the world to come. The notion of displacement lies at the heart of all missionary activities and is central to understanding the mission of God in the world. Here are six brief theological frames that can greatly assist in developing a missiology for FDPs:

God on the move

The idea of God in motion and motion in God is foundational to conceiving a Trinitarian and missionary God.13 It is a way of understanding God’s sovereign reign and God’s ongoing activities in our lives and the world. This makes God of the Bible alive and at work in the world, unlike lifeless and motionless idols that need to be carried from place to place by their devotees (Jer 10:5). This idea of a moving God makes the divine being capable of love and relationship and thus affecting the communion between the Creation and the Creator. As the Son of God, Jesus moves by taking on the flesh of humanity as one who is lowered, poured out, and full of compassion and suffers to redeem a fallen humanity. Furthermore, God establishes kingdom reign primarily through the dispersion and displacement of his people by moving them into all the world.

God on the move is the beginning point for ministry among and alongside FDPs of the world. Besides the dimensions already mentioned above, God on the move is clearly evident when God is presented as a Good Shepherd who goes after the lost and scattered sheep to bring them back and bind up the wounded (Ezek 34:11-12; Luke 15:4). Also, the woman who carefully searches to find the lost coin (Lk 15:8) and the father who runs to welcome and restore his wayward son when he returns home (Luke 15:20). Similarly, the Good Samaritan attends to the injured man who fell among thieves by bandaging his wounds and taking him to safety and paying for his further treatments (Lk 10:33-35). Finally, there is the picture of Christ himself who took the form of a bond servant or a displaced slave. Incarnation can be perceived as a divine displacement where Christ moved from heaven to earth and made salvation possible (Phil 2:5-8).

Some of these images allude to celebration which is also a movement from grief and mourning to joy and thanksgiving. They all underline the movement that happens for the sake of divine restoration. God loves and moves to transform the world by building a people and establishing the divine reign. Andrew Walls notes that in the Bible God used migration either in an involuntary and punitive way or a voluntary and hope-driven way, but both movements are redemptive.14 Displacement is a redemptive movement as it connects to the mission and purposes of God. God is moving to the nations and calling people to move toward the divine self. Displacement moves people into God’s trajectory, and this moves them on a journey of intersections and directional changes. The formula for God’s mission and purpose is also one of movement: repent and follow. Repentance is a directional change and those who follow Christ move as he has first moved: to love, to serve, and to call and celebrate homecoming.

The Trinity

The Trinitarian conception of God in Christian theology makes sociality and communality possible. The Trinity underscores the living and relational nature of the divine being. Some of the core elements of Trinitarian theology that are helpful for ministry in the context of displacement are: a) There is one God in three persons. God is not divided into complex parts. b) God is always the subject of the Trinity with the names Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. These are three persons who are fully actuated, complete, and whole. c) Together they always act as one and they are never in competition with each other or the creation. d) God is always for us.

These principles remind us that in displacement there is no situation that is too complex or impossible for God. The Trinity demonstrates how the different parties in displacement can also find wholeness, life, and community together. In the Genesis account, we see these different parts at work. God sees, calls, separates, makes, places, creates, blesses, and more. The Spirit of God is moving over the surface (Gen 1:2). References to the Trinity also show up throughout John’s writing who explains the Word was with God in the beginning and nothing came into being apart from him (John 1:2-3). Regardless of whether these are expressions of the Trinity or not, the creation account establishes the one God who fully creates the world and humanity in harmony with one another.

Trinitarian principles like these are gleaned through the steady process of living a life of faith and proclaiming this.15 The unity of the One God expressed in the Trinity comes from the different parts moving in and out of each other in perfect harmony. There are no alliances or tritheism. Rather, there is a perfect communion in the three where the one relates to the other. In creation, the Trinity is evident, because when one part is active the other two are fully there. No one person acts individually. Jesus says he follows the command of the Father on his initiative (John 10:18) and that he and the Father are one (John 10:30). The Father’s command and work extends through the Son and is completed by the Holy Spirit.

Already in the complex diversity of creation in Genesis, the Trinity is at work holding all things together, linking opposites and different parties together. The holy community of the Trinity becomes a paradigm for the human family. But what happens in the aftermath of the Fall and the context of forced displacement when the person asks questions like in Psalm 22, ‘Why have you forsaken me and why do you not answer? Who is God now for the displaced person and where do they see God at work?’

The challenges of forced displacement are dwarfed in comparison to those of the Trinity. The differences in the Trinity are infinitely larger than those of forced displacement. The Trinity provides a roadmap to navigate the boundaries and overcome the immeasurable differences of others. God transcends and enters this world from the outside, yet God indwells the world and every place of those forcibly displaced, so there is no place too low, too high, or too dark away from the presence of God. Darkness and light are alike to God (Psalm 139). The Trinity holds these opposites together and makes the impossible possible.

The image of God

The image of God has been with humanity since the Creation. God embeds the image in each person to establish the value, worth, and dignity of human beings. For the displaced person, the image of God serves as the only remaining link to the creator when everything has been lost. The image of God is an essential part of a person as it gives them a sense of identity and belonging. At the very beginning, before God created man and woman in the image and likeness of God (Gen 1:26), the world was formless (Gen 1:2). In this void, God begins to put all the structures of creation into place and then God finally adds humanity as the likeness and image of God. The image then crowns the creation giving man and woman the core essential structure they need to find meaning in the world and community with God.16 Jesus said the essence of the law is to love God and to love our neighbor (Mark 12:29-31), and in the same way the image of God is the essence of creation.

Just as there is an essential structural understanding of the image of God, there is also a representative and relational understanding. This understanding emphasizes man and woman are created to be in community with each other and with God. The unity of the person is found then in the image of God which in turn flows out of the unity of God, who says ‘Let Us’ make man and woman in ‘Our’ image.17 Karl Barth says, ‘The image does not consist in anything that man is or does. It consists of the fact that man himself is God’s creation. He would not be man, were he not the image of God. He is God’s image in that he is man.’18 Created in the image and likeness of God, human beings function as representatives of the invisible God. The image finds its expression through the activity and function to represent God. The image of God makes the person fully capable of functioning in this way as a whole person without distinction of body or spirit.

Yet, after the Fall the image has been warped and broken and humanity has been displaced, exiled, and banned from their home with God (Gen 2:23-24). Ever since this first displacement of humanity, each person now has lost and left everything that makes them complete and at peace in creation. The aftermath of the Fall includes a loss of place, with endless searching and wandering, murder, violence, terror, and fear that only a flood can cleanse in a kind of de-creation.19 The narratives in Scripture tell the accounts of one displacement after another where human beings are outcasts and homeless. This is no different from the experience of displacement for many today.

The image of God, although shattered and broken has not been lost, and it is the one thing a person carries with them through many displacements of this world. In this way, the image of God continues to connect the person to the Creator. Many displaced people who have lost their former lives will ask ‘Who am I now?’ and ‘Where will I go next?’ These are questions related to the image of God. Who is this person now since all the previous structures, family, and community are gone? And where will he or she go to rebuild a life and find a new community? Particularly, when a person is forcibly displaced there is an acute sense of loss, grief, and injustice. The image of God is essential for renewed identity, emotional well-being, and wholeness. It is the seed for the new humanity realized in Christ (John 12:44-45, Col 1: 13-15). It makes displaced people essential vehicle and representative of God’s grace and redemptive plan. The image of God, like the Trinity, is a cornerstone for missional interaction in a world of displaced people.

The presence of God

The expulsion from the Garden sends man and woman into the world. However, being created in the image of God, the expulsion also means they carry the presence of God with them into the world. The presence of God was in the first expulsion as a promise of God’s provision in the world. God was with Joseph when he was sold into slavery (Acts 7:9) and dwelled among the people as they passed through the wilderness (Exod 29:45, Ex 40:34, Isa 63:11,14). The divine presence guides, supplies, comforts, gives rest, and brings hope and courage. The presence brings blessing and makes possible divine peace, protection, and providence. Just as Abraham set out on his journey based on the promise of God, the believer has the hope of Christ as the same promise and presence of God (Heb 6:13-15,18). Displacement makes it difficult to see the presence of God, yet God has not abandoned the displaced. Through the incarnation, Jesus came to dwell with humanity as Immanuel (God with us). In this, God moves into human suffering and is present in all sufferings. To speak of God’s divine presence in forced displacement means God sees, hears, and cares—even the one who is alone in a foreign country, wandering in the desert, stranded at sea, or stuck in prison.

In Matthew 25, near the end of his earthly ministry, Jesus explains the nature of his return that entrance into the kingdom will be a question of vision. How well do we see God in the face of others in need, the stranger, the sick, and the imprisoned? Ministry in a forcibly displaced world sees the presence of God in those who have been sent to us as strangers and neighbors. God sees, hears, and cares, but how well do we see and hear God? How well are we following and modeling these elements at the core of our faith in God? It may mean we need more opportunities to be present with God. Similarly, at times it is more valuable just to be present with a person. The presence of God is the basis for understanding God’s provision and the significance of the cross in our lives. If we struggle to forgive our enemies or to make a connection to strangers among us who are different from us, then we may need to revisit our understanding of God’s presence, the Trinity, and the image of God.

The mission of God

The mission of God follows like a bookend, and it happens through the displacement, first of God’s Son and second of God’s people. Displacement is more than an exception or a crisis to fix. It is the way God has chosen to transform and establish his people and kingdom. Since the expulsion from the garden, God’s plan for redemption has included strangers and nations. Thus, God is a missionary God whose heart beats for all people everywhere.

Both Elijah and Elisha’s ministries show this heart in their ministry to the widow and the leper Naaman, both foreigners outside the nation of Israel. God’s plan from the start has been to bring the nations back to himself. God’s plan to include the nations was a mission outside the box and beyond the ways most people could imagine. God’s mission through Jesus is not business as usual and he faced opposition from the very start (Luke 4:28-30). Jesus develops the understanding of God’s kingdom as the scattering of seeds (Matt 13:3-9), which evokes the image of displacement and dispersion. Displacement is the building plan for the kingdom of God. In his journey to the cross, Jesus ‘set his face toward Jerusalem’ (Luke 9:51) developing further the trajectory of the mission that he was on by displacing into his world. God’s plan means our mission is to love God and to love others (Lev 19:33). In moving to the nations, God calls people to move toward him. Displacement therefore is a mission movement. Abraham followed God’s call without knowing where he was going (Gen 12:1, Heb 11:8). God moves people through the displacement trajectory on a journey of intersectional and directional changes.

Abraham learned that the journey of faith is life-giving. Paul’s missionary journeys begins with displacement (Acts 9:23-30), and displacement is at the heart of Paul’s defense before Agrippa in Acts 26. Paul references his travels, displaced among the nations for the mission of God (Rom 1:1-6). He sees the force of displacement and hardship as God’s way of moving the mission forward (1 Cor 16:3-12). In this manner, Paul develops the understanding that mission and human mobility belong together. Paul invokes the image of Christians as displaced prisoners in a triumphal procession that serves God’s mission and strategy in the kingdom of God (2 Cor 2:14-17). The difficulties that accompany displacement emphasize how God accomplishes his mission in every place and despite every obstacle. Arguing against his accusers, Paul reverses the normal expectations of a successful mission to emphasize the extraordinary nature of grace that God employs in situations of weakness like his own flight and displacement from Damascus (2 Cor 11:30-33).

Hospitality

In the New Testament, the Greek words for hospitality and hospitable are philoxenia and philoxenos, and the roots of these words mean ‘love for strangers or foreigners.’ These Greek words remind us of another term that is frequently used nowadays: xenophobia, which means exactly the opposite, ‘fear of strangers or foreigners.’ The hospitality taught in the Bible is not the kind of hospitality we show to our friends and family members, or people who are ‘like us.’ Being generous, kind, and hospitable to the people who are already ‘one of us’ is not biblical hospitality. Jesus challenges us, ‘When you give a luncheon, do not invite your friends, your brothers or sisters, your relatives, or your rich neighbors; if you do, they may invite you back and so you will be repaid’ (Luke 14:12).

In the same Gospel a few chapters earlier, Jesus told the Good Samaritan story to answer the law expert’s question ‘Who is my neighbor?’ (10:29). After finishing telling the whole story of Good Samaritan, Jesus asked the expert of the law again, ‘Which of these three do you think was a neighbor to the man who fell into the hands of robbers?’ The expert in the law replied, ‘The one who had mercy on him.’ Then Jesus told him, ‘Go and do likewise.’ (Luke 10:36-37) which is another way of saying, ‘Go show mercy and love your neighbor who is not your people, just as the Good Samaritan did.’ Jesus’ illustration was very counter-cultural for his time. From various passages in the New Testament (John 4), we learn that there were racial and religious tensions between Jews and Samaritans at that time. Why did Jesus tell a lengthy and culturally offensive story to answer an expert in the law with a simple question, ‘Who is my neighbor?’ (Luke 10:25-37) Is he not trying to say, ‘Your neighbor is the one who has mercy on you, and it does not matter what ethnic, religious, or political background they are from?’ And the most important thing is that he told us to do likewise to show mercy to those who are different from us. This is a key issue in forced displacement because of the basic human need to be welcomed as well as to welcome.

Shalom

Shalom is one of the primary themes of redemption that conveys a sense of wholeness, completeness, harmony, and fulfillment in life. Usually translated as peace, shalom is the positive result of God’s blessing, and it describes a place of safety and refuge that includes responsibility towards others in the community. Similarly, most displaced people in the world today will say they are looking for safety, ‘I just want to live in peace.’ Therefore, the aims and needs of FDPs align closely with the development of shalom in Scripture. Shalom denotes what a person has because of being connected to God’s promises. In the difficult context as sojourners Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob have the reminder of the covenant promise (Gen 15:12-21, 28:18-22, 44:17). The long-lasting friendship between Jonathan and David not only guarantees safe passage for David but also God’s promise to the descendants of David (1 Sam 20:7,13,21). Shalom refers to God’s blessing, protection, safe passage, refuge, and future hope. It also signifies the reward for doing the right thing, and it carries the idea of responsibility to walk in God’s ways. In these ways shalom describes both what God’s people receive and what they do in relationship to God’s promise and blessing.

The largest use of shalom in Scripture refers to the covenant of peace and it reminds us that God is the source of peace. Psalm 4:9, 122:7, and 147:14 reference the safety, security, and salvation of God. Many Psalms refer to a refuge and develop the idea of shalom even though the word is absent (Ps 4:8; 29:11; 35:27; 120:6). These remind us that God stays intricately connected to his people to bring them through to a place of peace and safety. Shalom grants a place of refuge and also carries expectations of responsibility. The use of shalom in Scripture relates to the result of right living, highlighting the importance of responsibility in relationship to God’s kingdom. In Psalm 34:8-14 the writer praises God as a refuge but also calls the reader to ‘fear the Lord, to depart from evil and to do good, seek peace and pursue it.’ Those who experience shalom because of right living take on fully positive and important responsibilities in the development of God’s kingdom.

Isaiah prophesied the Prince of Peace would bring a new order; he would be a suffering servant to bear the iniquities for the sake of well-being (Isa 9:6; 53:5). The prophets develop further both what shalom gives and the responsibility that comes with it. God called exiled people to live out their faith based on who they are and where they are, ‘build houses. . . plant gardens . . . take wives . . . and to pray for the welfare of the city’ (Jer 29:5-7). This avoids isolation, facilitates integration, and makes a long-term difference in the host community. The prophet connects the call to faithful living in Babylon to God’s plan of shalom—for their peace and future hope (Jer 29:11). Their peace and well-being in Babylon, will depend on the same shalom being lived out in the larger community. Thus, shalom stands more for societal transformation through peace, well-being, and responsibility in external relationships than as a sign of inward peace.

The current day impact of displacement on society and the polarization and confusion that accompany this highlights the importance of understanding shalom in forced displacement. Shalom signifies the peace of a future hope. The Biblical Exile encompasses efforts to integrate and overcome loneliness. Likewise, the development of shalom reflects an interdependent community of local and foreign citizens with more skin in the game than simply the next handout to organize or receive. Where shalom is involved, we find a community characterized by mutual understanding and reciprocal efforts, with the blessing of shalom as the mortar for this cohesion. In this kind of community, both sides understand the other’s perspectives. It is an expanded vision capable of seeing not only one’s own concerns but also the others. In the New Testament the redemptive benefits of shalom become clear. Jesus promises peace in place of fear (John 14:27) and calls us to see others in his place (Matt 25:37-40) is a vision of heaven that like shalom shapes people’s ethical decisions. Finally, the cross of Christ promises a place of peace and eternal security for all.

Effective Ministry among FDPs

God calls the church into mission and ministries that are life-giving. In the context of FDPs, this kind of ministry builds resilience and brings hope. Resilience is the ability to bounce back and recover from impossible odds. It is the strength of character that helps a person to overcome vulnerabilities or dependencies and to recover as a normal functioning human being. Hope gives the person undying confidence for the future. It is the result of faith, and this is why many FDPs hold tenaciously to prayer and faith.

In December 2012, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) held a Dialogue on Faith and Protection which noted the crucial role faith communities play for FDPs. The moral standing of the faith leaders creates positive attitudes in both refugees and host communities. They are needed to make informed decisions and sustained differences in the lives of FDPs. The High Commissioner concluded, ‘For the vast majority of uprooted people, there are few things as powerful as their faith in helping them cope with fear, loss, separation, and destitution. Faith is central to hope and resilience.’20

For Christians, the realities of resilience and hope originate in Christ and nurture wholeness and well-being in FDPs. They are like the spring of life that comes forth from the Lord (Joel 3:18) and promises flourishing and unending life (Isa 58:11). Resilience for FDP is like a well of life and the hope of Christ fills this well. These ministries among the forcibly displaced strengthen faith, hope, and love as expressions of God’s new creation in Christ. Churches not only need this kind of ministry, but they also need people like FDPs who thirst for God’s water of life (Rev 21:6) and who have first-hand experience on the frontlines of faith. The following are important practical considerations for ministry among FDPs.

Relationships of trust and respect

FDPs face a daily stream of practical needs and challenges that include vital transactions like providing shelter and food. When unmet, they erupt into a major crisis and even result in death. It’s easy to become overwhelmed by these needs. FDPs also face a corresponding crisis of the soul with needs of identity, security, and belonging: Who am I? Where will I be safe? And how will I fit in? Displacement raises these needs and questions deep in the soul and they are best addressed through relationships of trust and respect. Therefore, effective ministry is not only transactional but also relational. Trust for a forcibly displaced person is the choice about how they will interact with others. Trust is a sign of this interaction. Most of the time trust among FDPs has been eroded and it is replaced with mistrust. On the other hand, they feel respected when others show interest in them and consider their needs and concerns. Effective ministry models itself on the example of Jesus who not only chose his followers but also allowed them to choose their interaction with him. This requires more than a transaction. It opens the door to trust. Trust comes through a mutual walk of working daily through issues of reconciliation and exemplified in relationships like that in the Trinity.

A relational ministry follows the example of Jesus’ incarnation and his promise to walk with his followers. Among FDPs, such ministries are proven by the time spent with another person by visiting, listening, and sharing life together. The involvement with FDPs that model Christ’s presence in his followers becomes the basis of transformation and faith. It is more than a transaction; it shares Christ person by person, heart to heart, and day by day; and often without words. A relational ministry of trust and respect is rooted in the image of God, the presence of God, and the peace of God. These are the building blocks for identity, security, and belonging needed by every human being. Relationships of trust and respect are the prerequisite for transformation, conversion, and fruitful ministry among FDPs.

Trauma-informed ministry

A trauma-informed ministry recognizes the lasting effects of trauma on the physical, social, emotional, and spiritual well-being of FDPs. Trauma is the severe injury or force that causes repeated waves of recurring memories, nightmares, and daily interruptions in life and work. It is easy to understand how more than half—if not the majority—of FDPs in the world have experienced trauma. It is evident in their nightmares, insomnia, memory loss, difficulty in concentrating, fatigue, anxiety, depression, and PTSD. The asylum system such as detention only exacerbate these effects. Furthermore, the ongoing interactions with asylum officials, police, militias, and gangs can trigger more effects. Trauma puts people at risk of further injury as well causing trauma to others. Ministry among FDPs needs to grasp the nature of trauma and it needs to bring the light and life of the gospel to bear on the issue. Most of all it needs to utilize both local experts and local communities to address trauma.21

A healing group is an example of trauma awareness in action. It is the accompaniment of others in the recovery from trauma. In a series of planned gatherings, these groups address difficult and important questions such as: ‘If God loves me? Why do I suffer in this way? How can the wounds of my heart be healed? How can I grieve well? What can take my pain away? How can I forgive?’ Ministries must help FDPs realize that they are not alone in their questions and a normal life is possible.

These healing groups do not replace professional help, instead, they leverage the power of God’s people in community who give each other permission to openly express their burdens, listening to and comforting one another. The group approaches trauma healing as a journey and not a program. The leaders of healing groups have themselves processed their pain and trauma and have been through training. It is said that hurt people hurt people. Likewise, it can be claimed that healed people heal people by sharing their healing journeys.

A healing group creates bonds of trust. People start to feel safe again to share their hearts without fear of being judged. Little by little, the community grows, and people begin to feel well again. Brokenness is part of life, but God is very close to us when we are hurting (Ps 34:18, Rom 8:19-22). A community like this can lead people to a place of feeling loved again and special in the eyes of God (Romans 8:35, 38-39).

The prevalence of trauma is difficult to assess because many FDPs have learned to ignore it. Survival is the priority. Yet, ignoring the wounds of trauma does not help to overcome the challenges of forced displacement. Trauma only worsens over time. Once a woman shared,

‘Before I took part in the healing group, I was lost. I didn’t even care for my children. They would be wandering in the camp, and I was not bothered. One day, as I cooked, I put water on the fire, and I forgot about it. I had a young child who went to the kitchen, and suddenly I heard the child scream. My child had been burned by the boiling water, and now I struggle with the guilt. Trauma healing has helped me become a mother again.’

Trauma makes relationships difficult. Many traumatized people perceive and treat others, including God, as if they are enemies. They cannot receive love and care, nor can they give the same to their loved ones. Traumatized FDPs experience conflicted relationships whether in camps or cities. Children are not allowed to be children, and they must take on the role of adults. Likewise, parents struggle, and living in new cultures further impacts the needs they have. The honor-shame cultures of many FDPs complicate trauma healing. Many men often reflect on how life used to be where they found worth and honor. A traumatized person readily ignores the experiences that have lowered their former status. A medical doctor, who worked with a reputable international health organization is now jobless in a refugee camp. He jealously holds onto the old photos of his former job. These tell his story and the loss of social status, wealth, property, and family.

The roles and status of both men and women have been reversed and lost. Men fail to carry out their household responsibilities and often left to their wife and children. The losses experienced by men can cause conflict often resulting in violence or divorce. Such situations cascade into more trauma for children. Some men leave their wives when they come into the camps because the shame of not being able to care for their families is too much to bear. In waiting for jobs, depression sets in and in some extreme cases suicide, putting their families to greater difficulties. The survival struggles can push them into hopelessness where the moral and ethical sense of right and wrong is lost and misinformed due to the changing situations and worldviews.

Abraham lied when he was faced with similar difficulty under pressure in a foreign land (Gen 12:15-16). Like many FDPs today, he was vulnerable, defenseless, and eventually expelled from the land. Survival became his highest priority for Abraham. Yet, God did not reject him but blessed him. FDPs find themselves in a similar situation, often made to feel illegitimate, with no rights to education, access to job opportunities, or even to bury their dead. This can trigger layers of trauma. It is not unusual for Christians to turn violent and abusive at home, Christian women succumb to sexual exploitation to feed their families, or young men who are radicalized because they see no other viable options. These are consequences of trauma that ministries need to be aware of and willing and able to address. The trauma-informed ministries offer the hope of Christ and becomes the heart and hands of God to the displaced by bringing emotional stability, restoration, and healing into their lives.

In one refugee camp, participants in the trauma healing ministry, after experiencing their healing, have rediscovered their humanity and started building a healing community. They wanted to break the chains of silence and shame. They refused to be lost in the misery of trauma but decided to discover their deeper self-respect and self-worth, understanding that they are not responsible for the situation they are in now and that the current situations do not define who they are. In taking small steps together they learned how to survive as a group, knowing that together they are strong. This group formed an organization and has offered support through healing groups to more than 600 refugees, including the elderly and disabled. Their work is an example of resilience amid adversity.

Holistic Focus on Community and Mutuality

A holistic focus recognizes facets and needs among FDPs that range from identity, safety, and belonging to purpose and capacity.22 In general, holistic ministry is Christ-centered and it draws on the foundations discussed above related to shalom, hospitality, and the presence of God. A holistic focus creates the broad basis needed for stability to rebuild and recover life in all its fullness. A holistic focus values the community that can break the isolation that many FDPs experience. At the heart of the community is the need to welcome and be welcomed by others. Like the example above of a community-based healing group, welcoming communities are necessary for resilience. Sharing stories bonds people together and people realize they are not alone. A sense of community helps to overcome loneliness of forced displacement, especially in the wake of trauma.

Additionally, FDPs deal with collective trauma. Collective trauma is a prolonged type of trauma experienced by a group of people and requires collective healing in a community. A community helps to break the silence which is an important step in the healing journey. In silence, FDPs hear voices of darkness that fuel the pain and drive the jealousy, resentment, anger, and desire for revenge. Churches that open their community to FDPs are practicing love for one another and hospitality to strangers. To know and love FDPs, churches need to invite them, listen and understand their context just as we help them to understand ours. This will not happen with Sunday services alone, rather it requires a focused time and space.

These community gatherings deepens the well of resilience. It treats the FDPs like ‘local colleagues’ who are full of insights and not as threats, problems, or case studies. In such communities, FDPs are the experts of their experience who can identify solutions that work.

Trauma healing efforts alongside local church communities in refugee camps have been successful because these events don’t involve outside experts who come to fix emotional crises. Instead, they succeed through local teams of church communities and refugees that work as partners to see what God sees. The results are overwhelmingly positive and beyond expectations. On a theoretical and missional level, these ministries and communities are examples of interfaith dialogue and intercultural learning. They serve as gateways into each other’s world with mutual openness and sharing their journeys and hopes.

Holistic focus in ministry also looks for ways to affirm a person’s purpose in life. FDPs are more than people in need. They bring a wide range of resources and capabilities even while they have managed to make it as far as they have with nothing. They are looking for ways to take charge of their lives and care for their families, to restore dignity, and to establish new relationships again. They are not looking for handouts as many people imagine. Instead, they are eager to develop capacities needed for a new life whether it be language, skill, or qualification that can help them to thrive.

In forced displacement, everything is new and changing fast, and it takes time to learn and accept new ways. Most FDPs have been taken advantage of, for example, by working hard for less pay or no pay at all. The churches can protect FDPs from such exploitation in refugee camps, cities, and countries of resettlement, by helping them understand the labor laws and other procedures pertinent to them. The newcomers need to know what is allowed and what is not, helping them to stay on the right side of the law. A new refugee once admitted, ‘I cannot stay connected to one community because you find engaging in conversations that are not helpful. While it is important to associate with people who look and speak like me, I found it necessary to find a local community that could help me integrate into the society.’

Finally, the holistic focus is important because it recognizes the two-sided effect of ministry. The host communities need to let go of their prejudices and receive healing as much as those who are coming as strangers. A holistic focus recognizes that the strongest ministry is a mutual one where healing happens on both sides. In this way, the displaced themselves are equally involved in ministry. A local youth group once developed a weekly ministry serving and sharing a meal with refugee minors. After some months the leader reflected, ‘We began this ministry thinking that we would help them, but they have actually given us the most.’ This kind of ministry is more than transactional, and it grows out of reciprocal relationships that appreciate what others contribute as a vital part of the ministry.

Unfortunately, mutuality in ministry is often inadvertently blocked by assistance and programs that ignore the FDP’s participation in building resilience as a human being. This is dehumanizing for FDPs and leaves them feeling undignified and worthless. Alternatively, the ministry must take the time to listen to their stories and to seek their wisdom. The church communities can provide FDPs an opportunity to share their stories with others who are willing to listen, and who will help to bring their pain to God, as their healer. Community groups like this provide a safe and stable place that offers God’s shalom.