The global church must think deeply about the relationship between the governing authority and the authority of Christ. Recently this dynamic tension between the two has become evident both internationally and interpersonally. When travel, gatherings, and churches were curtailed and closed, many Christians began to ask for the first time, ‘Must I obey?’ Fortunately, this is not a new question. We can rely on the Scriptures, church history, and the testimony of those who have gone before us.[1]

Authorities in Scripture

Authorities in Scripture

In the very act of creation, we see that God desires and ordains order. It is natural within the unity-in-diversity of the Trinity. Our freedom to flourish in loving and right relationships with God, neighbour, nature, and self always requires an appropriate form, lest anarchy results and life disintegrates. As such, a healthy ordering of society is a gift because it reflects our Creator, and this order provides blessings for all of humanity and creation. God’s intended order undergirds and empowers humanity’s commission to have dominion, be fruitful, and multiply. This pattern continues into how humans are ordered, relative to but never dominating each other, in a civil society that tends and keeps culture as God tends and keeps us (Gen 2:15; Num 6:22–26).

The global church must think deeply about the relationship between the governing authority and the authority of Christ.

While the world is not perfect and no human governing authority is, Christians can have perfect peace amidst rising and falling world powers because we know the sovereignty and authority of God. The Apostles Paul and Peter also admonish believers to submit to governing authorities (Rom 13:1; 1 Pet 2:13–14) because they exist for our blessing under God’s authority and order.

Christ, who now sits at the right hand of the Father, prefaced his kingly edict (the Great Commission) by saying, ‘All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me’ (Matt 28:18). The command to make loyal subjects of King Jesus implies that the rest of humanity (those not following Jesus) are presently under another authority. A Christian’s allegiance to Christ should be absolute, first and foremost. And yet, worldly kingdoms are allowed to rule because they still have a purpose in God’s plans.

A fitting analogy is that of parents who leave their children with a babysitter. A babysitter is invested with responsibility and authority by the parents and will give an account to the parents when they return. So what should the children do if their babysitter asks the children to watch a film the parents have forbidden?

Now we clearly see the tension. Many governments have put laws in place that resist Christ and curtail his commands, including the Great Commission. If Christ has the utmost authority and allows governments to rule under him, what shall we do when those governments contradict Christ’s clear commands and God’s good plans for shalom?

Biblical Models

Biblical Models

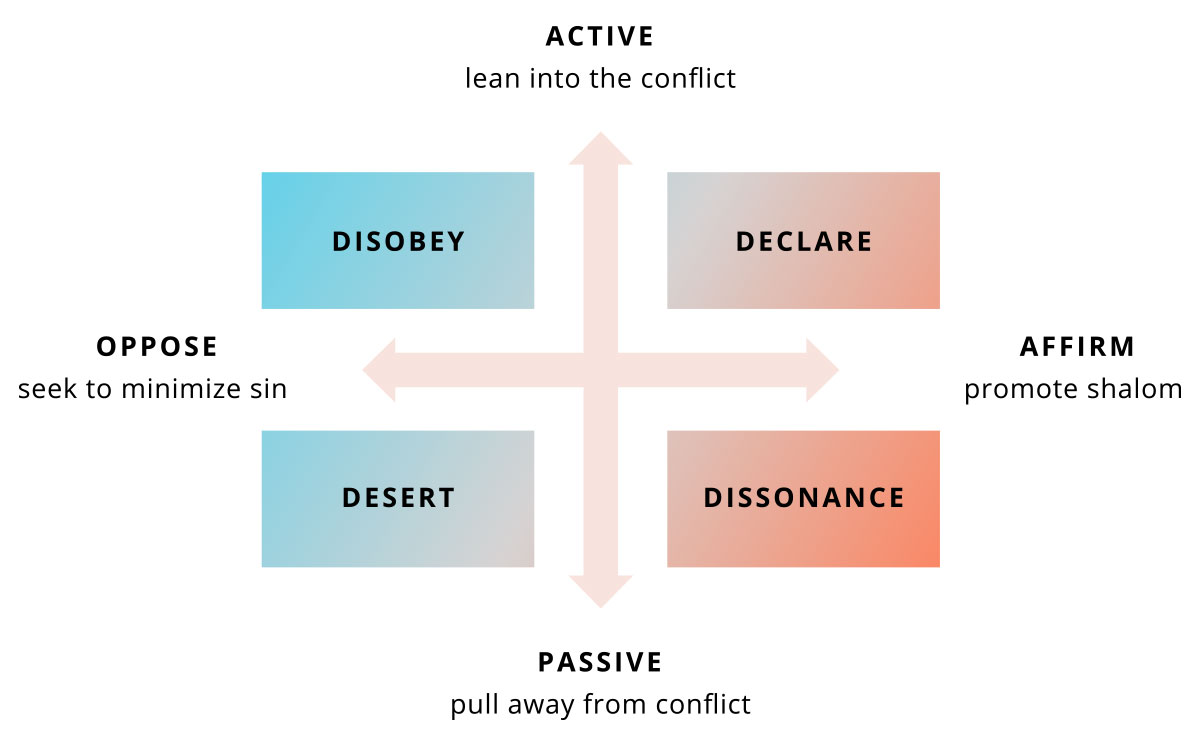

Simplifying as far as possible, there are (at least) four ways we can respond.[2] Each type is seen in the early church as the tension between following Christ and submitting to the authorities. Based on this framework, a helpful missional question arises which we would do well to ask ourselves.

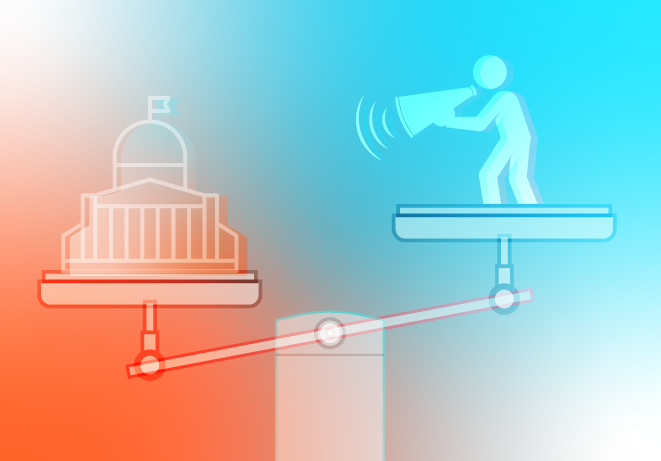

The first model is to declare truth. This is a strategy of positive engagement and promoting shalom. In the analogy of the babysitter, the children have the right to speak up and voice their opinion, speaking truth to power and sharing a better way to spend time together based on the wishes of the greater authority (their parents). We see this with Peter and John in Acts 4. The religious leaders put them in prison and then command them to stop teaching about Christ, to which they politely but resolutely refuse.

Declaring Christ’s kingdom requires active engagement in hopes to change culture, laws, and leadership by announcing the gospel of the kingdom and its implications for the civil society.

Declaring Christ’s kingdom requires active engagement in hopes to change culture, laws, and leadership by announcing the gospel of the kingdom and its implications for the civil society. Christians have a duty to cast a biblical vision for a just society and labor towards those ideals for the upbuilding of a truly ‘common’ good. This requires boldness, as we see the disciples pray in Acts 4:29. In our time and place, it is wise to ask: how might I live and declare a better story of the world set right, which relativizes political spin?

The second way is to disobey. This too is an actively engaged posture, but it leans in the negative or critical direction. The aim is to minimize sin by exposing evil and opposing injustice, albeit in a civil way that honors Christ as king and acts in line with his character. In Acts 5, the apostles are put in prison for not obeying the direct orders of constituted authorities. When the angel sets them free, he gives clear instructions to do the opposite of what the leaders said, directing the apostles to ‘go and stand in the temple and speak to the people all the words of this life’ (Acts 5:20, ESV). When confronted about their disobedience, Peter and the apostles reply, ‘We must obey God rather than men’ (Acts 5:29, ESV).

Today there are underground churches who intentionally and willingly break the unjust laws of the country by meeting and sharing the gospel and speaking against mistreatment of fellow humans and the world God made. In instances like this where faith in Christ is prohibited, it is impossible to follow both God and human directives. In our time and place, it is wise to ask: what political edict must I disobey to remain faithful to Christ as Lord and continue his mission in my context?

When the early church was persecuted in Jerusalem, it was dispersed to surrounding regions, counterintuitively advancing the spread of the gospel, and they lived to serve another day (Acts 8).

A third option is to desert or flee from the situation. This is a passive/disengaged response on the negative end of the spectrum, minimizing sin by escaping the tension between following Christ and obeying an unjust government. If the ‘babysitter’ is violent, one would expect the children to flee the home. Jesus himself said, ‘When you are persecuted in one place, flee to another’ (Matt 10:23). When the early church was persecuted in Jerusalem, it was dispersed to surrounding regions, counterintuitively advancing the spread of the gospel, and they lived to serve another day (Acts 8).

A modern example of this is a Russian ministry leader who fled the country for fear of punishment after his public condemnation of the war in Ukraine, as it is against Russian law to speak against the war. When asked why, he said, ‘I went against the government because they chose to go against God. I do not want to be a part of killing and decisions against the law of God.’ In our time and place, it is wise to ask: how might Christ be making a way for me to desert an overbearing regime and make space to faithfully follow him to new frontiers?

A final strategy is dissonance. This is passive obedience to the law. It is calculated acceptance if you are forced to obey—thus still on the positive/constructive end of the spectrum—recognizing the messiness of living between two competing kingdoms before the final judgment.[3] If we envision an oppressive babysitter, the children might choose to go along with an errant command for the safety of others in the home, like looking out for a baby brother who cannot leave. Or perhaps they prayerfully persist under poor minders to maximize genuine goods which would be lost were they to run away, such as the opportunity to be a faith-full presence in the neighbourhood (1 Tim 2:1–4).

Dissonance should never be an excuse to disobey Christ’s clear commands or promote policies that do.

These are gray areas where it is not clear whether obeying one authority means disobeying the other. We saw this with some churches who did not like Covid restrictions, but chose to abide by the law for the sake of witness to an onlooking world. Perhaps many of our brothers and sisters, who cannot flee oppressive governments, have decided to remain quiet about teaching on certain issues so that they can continue to seek first Christ’s peace-full kingdom and point people to Jesus in other ways.

Dissonance should never be an excuse to disobey Christ’s clear commands or promote policies that do. It is not a vague option or last resort for those without moral conviction. Wise dissonance is calculated, carefully living in the paradox of sinful governments and a perfect kingdom out of love and concern for the welfare and flourishing of others.[4] Thus, Paul commends, ‘Make the most of every opportunity in these evil days’ (Eph 5:16, NLT). In our time and place, it is wise to ask: what good may come if I faithfully persist, following Christ amidst the dissonance, and how can I keep my bearings when authorities have lost their way?

Conclusion

Conclusion

Ultimately, we must rely on the leading of the Holy Spirit in various situations. We see the Apostle Paul adopt one or more of these ways, depending on the situation. He flees from Damascus in the cover of night. Yet he actively preaches when he knows it is dangerous to do so. Finally he is taken to Rome, captive. He does not try to flee when given the opportunity on Malta. He trusts God’s plan for him unto death in Rome, making the most of his remaining time to preach about the kingdom of God while under house arrest (Acts 28:30–31).

What can help us navigate this cultural moment in complex times? The Apostle Peter offers insights before he commands believers to be subject to governing authorities. He says, ‘But you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for his own possession, that you may proclaim the excellencies of him who called you out of darkness into his marvelous light’ (1 Pet 2:9, ESV).

First, we need to go back to the heart of our identity in Christ, knowing our primary citizenship is in heaven. This will help set us free from purely worldly attachments (1 Pet 2:16). If we syncretize our faith with our nationality and allegiance to the government, it will be hard to discern loyalty to Christ when times of tension arise.

Second, we are to be morally pure. Being ‘exiles and sojourners,’ we are to abstain from passions of the flesh (1 Pet 2:11). Peter admonishes us to live to a standard of godliness and purity, which is not always the same as following civil law. We are called to be purer than governments require. Even if the world hates our gospel and our message, it will at least acknowledge our good deeds and glorify God one day (1 Peter 2:12).

Finally, we must remember why we are called. Our primary purpose is to shine like Christ. We can bolster the identity of the church by submitting to governing authorities as best we can. We should not be identified as restless, irrational, or instigators of chaos. Then, if a time arises to disobey, the world will see our Christ who lovingly beckons our ultimate allegiance.[5]

Endnotes

- A fuller conversation would, in a principled way, bring together wisdom from Scripture, tradition, scholarship, experience, and even the arts, all self-reflectively interpreted and grounded in the ‘norming norm’ of what we believe God has spoken in his word. For a healthy hermeneutic, see John G. Stackhouse, Jr., Need to Know: Vocation As the Heart of Christian Epistemology (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014).

- The following framework is informed by H. Richard Niebuhr’s Christ and Culture (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 2001), where the options may be understood as quadrants within a grid comprised of two continua: active–passive (alternatively, engage–disengage) on the vertical axis captures whether we lean into or pull away from the conflict; while positive–negative (alternatively, affirm–oppose) is on the horizontal axis and captures whether our stance is primarily upbuilding (maximising shalom) or deconstructing/evading (minimising sin). Rather than being seen as distinctive strategies in a taxonomy outlining all possible responses, it is best seen as a typology or lense through which one may look at any conflict between obedience to Christ and culture. In a complex situation we may adopt aspects of each type at the same time.

- For those Christians called to serve or lobby in politics, dissonance is also necessary. For in a pluralistic democracy, brokering a way forward between competing factions, we must seek what is optimal toward our vision of the kingdom for the flourishing of all (that’s justice), rather than simply being concerned for just us. What is ideal is rarely if ever possible, and only settling for a total win in all-or-nothing policymaking aligned with our values (such as seeking to outlaw abortion altogether and not partnering with those who would make it less likely than it presently is) typically costs meaningful gains in the right direction. Christian minorities must be ‘as wise as serpents and as innocent as doves’ (Matt 10:16). As Otto von Bismarck, first chancellor of the German Empire, observed, ‘Politics is the art of the possible, the attainable —the art of the next best.’

- For a compelling argument to adopt this approach, where principled compromise is a form of Christian realism in a broken world to maximise shalom and minimise sin, see John G. Stackhouse, Jr., Making the Best of It: Following Christ in the Real World (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

- Editor’s Note: See article by Babatomiwa M. Owojaiye, entitled ‘Christian Persecution in Nigeria’ in the May 2022 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis, https://lausanne.org/content/lga/2022-05/christian-persecution-in-nigeria.