Introduction

Missiological studies is heavily loaded with European and Western vocabulary and languages. This is partly because of the way the history of mission has been written and developed with a focus on mission from the West to the rest. As we continue to wrestle with the implications of polycentric missiology with attention drawn to Majority World mission, what vocabulary and languages are emerging from such contexts that can help us reimagine mission in the 21st century?

One of the things I am attempting to do in redressing this imbalance is to see how we can theologize, paying more attention to African languages, vocabulary, and slang. One of the slang terms that is currently common among Yoruba-Nigerian youths is Japa which means to escape or run away or take swift action about your future! This article illustrates how theologizing can be done by using the Yoruba word Japa to explore the intersection of mission and migration in Britain.

The Realities of Japa!

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a new wave of migration from the continent of Africa. This new wave of migration is now described by Yoruba-Nigerians as Japa! Many of the Nigerian and other African youths are trying to either escape the various economic hardships that their country faces or take matters into their own hands to fashion a new future for themselves by running away to Western countries perceived as greener pastures. Similar but different patterns are being observed among Hong Kong migrants and a term that has been coined by one of the Hong Kong theologians in the UK is ‘Runology’ to describe how Hong Kong migrants are trying to escape the political situation in their country.1 Whilst this Japa in Nigeria happens predominantly among the youth, it is not limited to the youth as there are others seeking similar route to escape. Some of the routes for Japa are through various visa schemes such as working as care workers needed in Britain, studying in Western colleges, and other opportunities.

In the last two years I have had conversations with my younger cousins who desperately want to travel out of the country by any means necessary due to thinking about their future prospects in Nigeria. Some of those conversations have been very difficult and sad at the same time. This is because firstly, I hear the frustration at the lack of prospects in the country that many Nigerian youths feel. Secondly, I notice the suffering that Nigerians are going through due to the global economic crisis that has occurred since the pandemic. Whilst this global economic crisis impacts everyone, in the case of Africa it is becoming critical as the pandemic realities have intensified the already existing economic and political struggles. But it is even more tragic to hear of the experiences of some people I know who have arrived in the UK through the care worker scheme—the exploitation through bad middle-management in the scheme; the shock of realizing that Britain is not a greener pasture as some have thought because of their daily struggle to survive.

Perhaps an important question to ask at this point is, does Japa have the potential to contribute to what I am describing as migrating witnesses in the West or is it a form of a brain drain on Nigeria’s human resources? When I left the shores of Nigeria on independence day (October 1, 2004), I left friends who were well-off financially and others who had good future prospects in Nigeria. They would never have thought of travelling abroad except for holidays and other social gatherings. Twenty years later, some of them have moved to Britain and other European countries because they have lost their businesses or the economic inflation has drained their resources. In my opinion, Japa, like other types of youth migration from other African countries, is a form of a brain drain on the continent. If Africa as a continent is going to be a major source of economic and political power in the future, surely it needs its youths who have the potential and the vision to make this a reality.

Daniel and the Hebrew Boys: Servants of Occupiers or Migrating Witnesses?

Regarding brain drain, one biblical reflection that comes to mind is the narrative of Daniel and the other Hebrew boys during one of the exilic periods. Whilst the city of Jerusalem was besieged by the Babylonians, the Babylonian king forcefully extracted certain young men from the royal family and nobility to be in his service. In essence, the best brains that Judah could offer at that period were being ‘colonised’ in the service of the Babylonian king. We therefore see Daniel and the three Hebrew boys offering their gifts and services to the king of Babylon. This text speaks to the issue of brain drain because the best human resources from Judah were taken by their occupiers. But the text also reveals another consequence: Daniel and the Hebrew boys also became migrating witnesses. They were able to engage in peaceful resistance and influence, disrupting the idea and imagery of Babylonian empire with a vision of Yahweh’s kingdom. The peaceful resistance was demonstrated by Daniel refusing to eat the king’s delicious diet dedicated to Babylonian deities. Daniel used his God-given gift to interpret the king’s dream and vision of a superior empire, but also revealed that Yahweh’s kingdom is the only everlasting kingdom.

Migrating Witnesses in the Diaspora2

If Daniel and the Hebrew boys experienced brain drain through colonisation, but nevertheless also became migrating witnesses, does Japa then have the potential to contribute to migrating witnesses in Britain? Migrating witnesses can best be described as Christian agents that God is using through diasporic factors to bring about his kingdom purposes on earth. In Acts 1:8, the Greek word used for ‘witnesses’ to describe God’s mission is ‘μαρτυρες’ from which the English word ‘martyrs’ is derived. This signifies that there is a cost to being a witness for God’s kingdom and this was clearly demonstrated in Acts of the Apostles with the death of Stephen and James, and through the patristic period of the many disciples of Jesus who died for what they believed. But the mission of God in Acts was also accomplished through the scattering of God’s people. The death of Stephen became a catalyst for the diasporic witnessing of the New Testament church.

Now those who had been scattered (διασπαρεντες) by the persecution that broke out when Stephen was killed travelled as far as Phoenicia, Cyprus and Antioch, spreading the word only among Jews. Some of them, however, men from Cyprus and Cyrene, went to Antioch and began to speak Greeks also, telling them the good news about the Lord Jesus (Acts 11:19-20; NIV).

In this text, the word diaspora is used to describe the scattering of the believers orchestrated by the painful witnessing of Stephen’s death. Therefore, it appears that God used the intersection of diasporic elements and witnessing to spread the gospel. If God uses migrating witnesses to achieve his kingdom purposes, then Japa, though a form of a brain drain as established, can also be a potential for migrating witnesses coming to Britain with their faith. The death of Stephen was the factor for scattering. In today’s context, factors such as the persecution of Christians, economic and political hardships, have resulted in Japa. Can the youths from the many African countries who are trying to escape become a mission agency in Europe? Their experience of suffering, hardship, liminality, and survival puts them in the place of understanding sacrifice. This combined with their faith could realize migrating witnesses.

Can the youths from the many African countries who are trying to escape become a mission agency in Europe? Their experience of suffering, hardship, liminality, and survival puts them in the place of understanding sacrifice. This combined with their faith could realize migrating witnesses.

I recently had the privilege of sitting in a meeting that was considering a Nigerian Pentecostal church plant in Britain. What I found striking in that meeting was the many Nigerian youths with a passion for Jesus who were present in that room. Whilst it occurred to me that we have lost many of our youths to Japa, it also dawned on me that these young people have the potential to become the new missionaries of today in Britain, therefore contributing to migrating witnesses in the West.

Collaboration with Migrating Witnesses

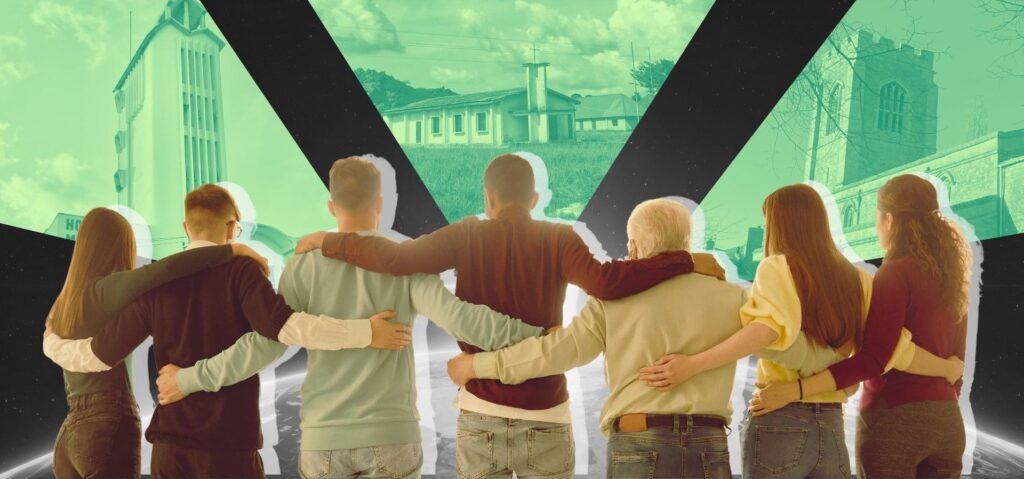

If these new witnesses are going to be effective, it will require an intercultural collaboration from and with British churches, discerning how we welcome and create a sense of belonging for this new missionary force. Our hospitality will have to go the extra mile in this instance against the secular tide of being inhospitable towards refugees and asylum seekers. Perhaps, a way to begin to address society’s xenophobia in our churches is to recognize that welcoming is not enough. We need to create a process that leads from welcoming, to belonging and integration. What would this look like?

Our hospitality will have to go the extra mile in this instance against the secular tide of being inhospitable towards refugees and asylum seekers. Perhaps, a way to begin to address society’s xenophobia in our churches is to recognize that welcoming is not enough.

Welcoming is that first step in our hospitality and should never be treated as the end result. Welcoming is intentionally creating spaces and contexts for new people to feel comfortable in our fellowship. Welcoming therefore goes beyond offering tea and biscuits to someone on a Sunday morning, it is ensuring that the new migrating witnesses feel comfortable in our churches.

Belonging is much deeper, as it goes beyond the introduction of welcome to again intentionally creating spaces and contexts for new people to begin to express who they are in order to feel they can belong. If welcoming is about comfort, belonging is about identity. Do migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees feel they can honestly share some of their struggles in our churches or do they feel they will be stereotyped, judged, or misunderstood? Can new migrating witnesses in our churches express the racism that some of them face both at church and society in our house groups? Creating a sense of belonging sometimes disrupts our comfort if we are not seeking to assimilate new people, or to understand where they are coming from.

Do migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees feel they can honestly share some of their struggles in our churches or do they feel they will be stereotyped, judged, or misunderstood?

Finally, we should be working towards achieving integration where new people in our churches, especially those from another country or an ethnic minority, do not feel like strangers anymore but an important part of our fellowship. They feel integral to what is going on in the life of the church because they have been included. They feel they belong because they can share about some of their struggles and joy. And most significantly, they are given opportunities to contribute to and share in the dynamics of the mission of the church, therefore realizing their potential as migrating witnesses.3

Endnotes

- Rev Chi-Wai Wu talked about ‘Runology’ in a presentation on Hong Kong migrants and their mission potential at a gathering of national senior church leaders called Intercultural Leadership Forum hosted at All Nations Christian College.

- Editor’s Note: See article Diasporas from Cape Town 2010 to Manila 2015 and Beyond by Sadiri Joy Tira in the Lausanne Global Analysis, March 2015.

- See article Decolonising mission: Jesus’s decolonial ethic of God’s Kingdom, Evangelical Focus by Israel Oluwole Olofinjana.