Following the global listening calls issued by the leadership team of the Lausanne Movement,[1] we may ask: what exactly are we listening to? How are we listening and (re)imagining in such a way that brings about transformative power? What are the pathways and characteristics of deep listening and (re)imagining that we embody as Christ’s followers? Thirty years ago, John Stott encouraged us to exercise the art of ‘double listening’—to God’s word and God’s world.[2] But he did not articulate what the posture of listening and (re)imagining is like as an artful act that brings multifold transformations.

Cultivate the art of listening and (re)imagining first and foremost by the grace of the Spirit through the verbal, the body, and the silence.

This article invites evangelical leaders to cultivate the art of listening and (re)imagining first and foremost by the grace of the Spirit through the means of three key aspects: the verbal, the body, and the silence. Only then can we listen and respond collectively to who God is and what God is doing in the world, and ultimately participate in the global mission of God (missio Dei) in a broken and divided world.

Intercultural Wisdom

Ancient wisdom in different traditions offers us endless treasure in the art of listening and (re)imagining. Australian aboriginal communities have long learned and practiced the importance of sitting, learning, and knowing. In welcoming guests to the art festival called ‘Yabarra-Dreaming in Light’ at the Tandanya National Aboriginal Cultural Institute, they sang: ‘You are invited to sit in the wodli and see what is around you; what you see you will begin to know. Look and listen to the ways of understanding . . .’[3]

This kind of listening is fully embodied with patient sitting, looking, and understanding to seek not just knowledge, but wisdom for everyday living. The 2021 Senior Australian of the Year, Miriam-Rose Ungunmerr, speaks about ‘tapping into that deep spring that is within us.’ The name of her tribe is Ngangikurungkurr, meaning ‘deep water sounds’.[4] Members of the tribe hold a waiting posture of listening till the ‘deep spring’ wells up from within.

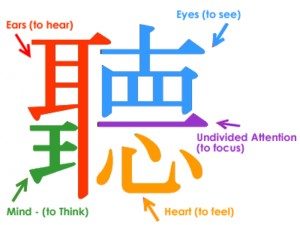

The ancient Chinese learned that the engagement of five composite elements form a holistic embodiment of ‘listening’. The Chinese etymology for the word ‘ting’ (listening, 聽) offers a constructive model that is made up of five elements that are required for listening: ears to hear, eyes to see, mind to think, heart to feel, and a single stroke for undivided attention:[5]

A fully embodied kind of listening requires respect and honor towards the other, while putting aside one’s own prejudice, presuppositions, and projections. It requires one to ‘stand under’ the other to gain understanding. Listening is therefore an act of humility, vulnerability, and patience.

The Verbal

Evangelicals are familiar with the notion of listening through the Word of God due to the unwavering commitment to the inspired Scripture as both normative and authoritative. Other Christian traditions can, however, enrich our imagination and intimacy with God. Lectio divina (‘divine reading’), an ancient method of reading the Word prayerfully and slowly, can help one to gaze upon the loving God and enter into a deeper communion with him. Contemplative engagement with Scripture allows one to read the Word, but more importantly, it allows the Word to read us and respond to our deepest yearnings.

We need to humbly listen to others—our colleagues, partner organizations, mission collaborators, and those whom we serve.

The turbulence of the pandemic, the Ukraine-Russia war, racial injustice, climate change, and economic recession could be likened to the storm the disciples experienced on the Sea of Galilee (Mark 4:35-41; Luke 8:23-25). By activating our imagination, we can ask where we are and where God is in the midst of the wind and raging waters. Are we in panic mode, frantically trying to figure things out, or calling out in faith or desperation to the Master? Doesn’t God care? Just having an honest conversation can bring us to the possibility of having our hearts transformed by God’s grace.

We need to humbly listen to others—our colleagues, partner organizations, mission collaborators, and those whom we serve. As leaders, we tend to speak more than listen. But could our listening be the first expression of love as a witness to others, especially the marginalized, the voiceless, and the vulnerable? Indigenous and contextual mission must emerge out of a deep sense of listening and imagining in the local soil, both among ourselves and with those we serve cross-culturally.

An often-neglected aspect of listening is our inner self-talk. Self-talk feeds our identity. The self-chatter behind the scenes can either trap us into the temptation of self-rejection or compulsion, or lift us up to a lifegiving path. When our inner voices are unearthed before a living God, we can name, discern, and respond by the empowerment of the Spirit.

The Body

Listening to the verbal goes hand-in-hand with listening to the body. The human body is sacred, holy, and wholly in Christ. It is not simply an object, but a person and a subject. It is the vehicle in which the spirit carries itself, like canvas to a painter and words to a poet. Listening to the body is an indispensable undertaking in order to honor and dignify ourselves and others.

In Jesus’ earthly ministry, he heard the people’s heartfelt cries and discerned their faith by observing their physical actions (Luke 5:18-20; 17:11-19). In the garden of Gethsemane, he listened to the body language of his disciples sleeping and saw that ‘their eyes were heavy’, and therefore discerned their weak flesh (Matt 26:36-46). He also listened to the body language of his opponents to discern the matters of their hearts (Luke 5:17-26; 7:36-40).

When engaging in local ministry or global mission, our physical presence embodies the presence of God

Today’s leaders often experience bodily fatigue and exhaustion when they work tirelessly in the name of Christ. If they had paid attention to the important signals of the body, many episodes of burnout could have been avoided at an early stage. When engaging in local ministry or global mission, our physical presence embodies the presence of God—just by being human, one with the other, in the act of incarnation. In doing so, deep consciousness can be brought to the surface through the body and the tangible touch of God can be experienced.

Listening to the body can be extended to the whole creation. Martin Luther claimed that God writes the gospel not in the Bible alone, but on trees, flowers, clouds, and stars. Indigenous people have a great deal to teach us about the redemptive work of God for the whole creation rather than solely for individual souls. The evangelical tradition insists on the important commandment of preaching to all nations (Matt 28:18-20), but can we also allow all God’s creation to preach to us as we sit and listen in the great theater of God’s glory? The natural world can minister to us and speak a new language of the goodness and beauty of God.

The Silence

Many Christians are not comfortable with silence. Our gatherings are usually filled with sounds, words, and activities. But silence is an important language and communication of the God of love.

God’s silence does not necessarily mean absence of movement or that God does not speak in the silence. It can be the very pregnant pause needed before the birth of a new era or a surprising breakthrough. First Samuel records the incident where God did speak, but it took the young Samuel four times to hear God (1 Sam 3:1-10). After a long pause, those who waited patiently for the arrival of the Messiah, such as Simeon and Anna, did hear God speaking in their communion (Luke 2:26; 37-38). When the scribes and the Pharisees brought a woman caught in adultery and questioned Jesus, they would have been wondering what Jesus was writing on the ground and trying to communicate in silence (John 8:3-11). The powerful two pauses (v. 6 and 8) become silent moments that invite the accusers to become aware of their own sinful lives and hence withdraw their fingers pointed towards others.

We need to listen to the silence of spaces for the wings of the Spirit to fly high in everyday life.

As leaders gather and listen together, are we listening to God in a new way in a new season? With all our questions and doubts, the silence of God may lead us into communion with God, who stands with us in all our suffering, brings comfort to the weeping, and rejoices with us in breakthroughs. When God comes to us in silence, can we capture his revelation just as when he comes to us in words? Sometimes the best response is to give it a shape through stories, poems, or pictures. Maybe it is precisely in this silent space that our (re)imagination can soar and engage in global mission in fresh new ways.

We need to listen to the silence of spaces for the wings of the Spirit to fly high in everyday life. The negative space of a painting or architectural structure makes the content full, not empty. The silent space flows from the surface towards the viewers for them to interpret and find their words. The pauses occurring in poetry take us from the familiar world to another unmanifested world. Without the space, we cannot have the shape or the unspeakable truth. The internal silence is expressed in the word ‘Selah’ (סֶלָה) found in the poetical books of the Hebrew bible. Although the Septuagint renders the word by division, it means a meditative pause, a suspension; to stop, weigh up, listen.

Waiting in the silence between exchanges while speaking to another, we try to receive the impact of the other’s words. The pause to reverence the sacredness of another, their thoughts and feelings, allows us to ‘chew and eat’ the message. The silent kenosis[6] state allows one to be an empty, broken, open vessel ready to receive God’s abundant life, a place where our ‘new self’ resides (Eph 4:24).

Conclusion

As the global body of the Lausanne Movement convenes, let us encourage each other to listen deeply, discern wisely, and (re)imagine creatively in the polycentric and polyvocal mission of God.

What would it look like for us to seek congruity with the living God by cultivating the art of holy listening and (re)imagining? Would it be possible that the Fourth Lausanne Congress on World Evangelization, planned to be held in Seoul in 2024, could consider ways of listening and (re)imagining especially by means of the body and the silence?

When we have an open posture by intentionally displacing ourselves and paying attention to the other, the wind of the Spirit may blow more loudly, and the still small voice of God may whisper to us more clearly in a time such as this. This requires sacrifice, which is often associated with the word ‘martyr’, a term that originally meant ‘witness’. As we embody sacrificial love by joining in listening together before the eternal and living Listener, we witness the transformative power of the Spirit in us and through us in a chaotic and polarized world.

Endnotes

- ‘The Evangelical Church Interacting between the Global and the Local: An Executive Summary of the Analysis of Lausanne 4 Listening Calls,’ Lausanne Movement, Dec 1, 2021, https://lausanne.org/l4/global-listening/the-evangelical-church-interacting-between-the-global-and-the-local.

- John R. W. Stott, The Contemporary Christian: An Urgent Plea for Double Listening (Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press, 1992).

- Dean Eland, ‘Eyes on the Street: See What is Around You,’ Loving the Neighbourhood, August 17, 2020, accessed 30th Sept 2022, https://lyn.unitingchurch.org.au/2020/08/.

- Miriam-Rose Ungunmerr, ‘Listening to Another,’ Compass Theological Review 22 (1988).

- ‘5 Listening Insights from the Chinese Character for Listening,’ SkillPacks, accessed 30th Sept 2022, https://www.skillpacks.com/chinese-character-listening-5day-plan/.

- ‘Kenosis’ meaning ‘self-emptying of Christ’.