Introduction

N joined a small team of pioneering workers to serve the people of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK; also known as North Korea) after hearing about their needs. As the small team did not have leadership on the ground, she did not receive orientation about cross-cultural ministry in the DPRK. She also found that most workers were busily engaged in their own work. She was extremely frustrated by the lack of leadership, training, support and team work. It was not a surprise that she left the field sooner than expected.

B was part of a project team inside a special economic zone. It was a small team, just him and another couple. Soon he was struggling with how the project was being run. Even though he was fluent in the Korean language, he was not prepared for the many occasions when Korean cultural values clashed with biblical values. Unfortunately, the team leader was not responsive to his many attempts to share his struggles. So he left the team.

P was lecturing at a University inside the DPRK. Each semester he stayed inside for some four months. During these four months, all the lecturers were under constant watch. He also had little contact with those outside due to security concerns. Every semester, he kept all his feelings and fears within. Hence when he came out, he was hoping to have someone to listen to his feelings and questions, and to give him counsel regarding his struggles. But no one gave him time, as they were busily engaged in their own ministries. Soon he developed severe depression and had to leave the field.

From a general observation, over the last 20 years there have been a number of Christian workers serving the people in the DPRK. Living and working in a place like the DPRK poses many challenges to the individuals as well as to those who provide member care for them. While many of the workers are still on the field, one has to admit that a significant number have left the field prematurely and many permanently. It is true that some of these attritions are unavoidable. Nevertheless, it should be acknowledged that, in hindsight, many of these attritions could have been prevented.

People Are the Most Important Resource

For every mission team, the most important resource is people. The World Evangelical Alliance (WEA) conducted a survey on missionary attrition from 1992-1994 called the ‘Reducing Missionary Attrition Project’ (ReMAP I). The results were published in a seminal book called Too Valuable to Lose: Exploring the Causes and Cures of Missionary Attrition.1 This survey was carried out on 23,000 cross-cultural workers from 455 agencies from 14 countries representing all continents. According to the survey, 3.1% of cross-cultural workers returned from the field each year prematurely, permanently, and for preventable reasons.2 This means around 12,000 cross-cultural workers return from the field each year.3 However, the negative impact is not only on the workers who leave. It also spills onto others. This attrition in turn impacts negatively on thousands of family members, friends, and sending and supporting churches in the home and host communities. This is also a huge loss in terms of personnel on the field. It also negatively impacts the particular team and the sending agency.

From a well-known study by Drs Lois and Larry Dodds, we have gained a great deal of understanding of the kind and the amount of stresses faced by cross-cultural workers.4 A typical cross-cultural worker experiences a stress level two times that of what could put a normal person in a hospital within one year! And cross-cultural workers in the first term peak at a stress level three times as much. These stresses are usually multiple, complex, and even unexpected. It is not only 2-3 times worse than living at home, but without the usual support structures. Of course, it varies between individuals and in the same individual at different times. Often, previously resolved issues can re- surface.

The above data and conclusion relate to workers in open-access nations. However, serving the people of the DPRK puts one in one of the most extreme creative access nations (CAN) in the world. By the sovereignty of God, a small door has been opened for foreigners to live and work inside the DPRK since the late 1990s. Despite the fact that they are welcome to make contributions in the areas of humanitarian aid, education, and business, they are living and working in a most challenging environment with long periods of isolation, constant surveillance, and lack of communication with the outside world. There are many more stresses they have to face due to the DPRK’s political ideology, cultural background, social infrastructure, and economic downturn (see Table 1 below).

| Table 1: Stresses as a Foreigner Living in the DPRK | |

| *keep watch on one’s speech

*keep watch on one’s actions *keep watch on one’s thoughts *practice Christianity carefully *restriction of movement *unreasonable demands for help *undue pressures to conform *unexpected delays and frustrations *pressure to compromise *building relationships with locals *feelings of hatred *lack of communication with the outside world *relating to Jucheism (self-reliance) *responding to poverty and suffering *clash with their historical view *handling propaganda *twisted view of Christianity *injustice *raising children and schooling *challenge with fund transfer *idolization of leaders |

*bribery/corruption

*poor business environment *impact of UN/US sanctions *isolation and loneliness *lack of Christian fellowship *cultural conundrums: gift giving, excessive drinking, chauvinism, etc. *obtaining residence visa *housing/permission to stay *lack of medical care *fear/doubt/discouragement *physical deprivation *ethnocentricity/pure race *group mentality *team issues *interrogation *arrest *deportation *detention *imprisonment *death |

According to the ReMAP I studies by WEA, lack of adequate member care is one of the main reasons why workers left the field prematurely.5 Member care is thus not an option! We need adequate member care to sustain people on a long-term basis on the field. Long-term impact arises out of long-term presence. Thus, member care is important not because Christian workers necessarily have more or unique stress, but because they are strategic. They are the instruments for sharing the light, the love and the life of Jesus Christ with those who are yet unreached.

Aim of Member Care

The aim of member care is to care for and build up the cross-cultural worker as a total person, so that he or she will be able to live and serve as a spiritually healthy and effective individual. There is thus a combination of pastoral care, Christian counselling, and human resource development.

We must intentionally provide resources that nurture and develop people (cross-cultural workers, support staff, and children) in the process of their joining an organisation, getting them to their place of service, setting them free to make their contributions, supporting them through trials, and bringing them home again at the appropriate times of their lives.

Preventive member care together with interventional member care will hopefully keep members healthy as a person and as a family. This will in turn enable them to serve effectively and productively. As a result, it is hoped that with adequate and appropriate member care, the attrition rate can be further reduced.

Member Care Model

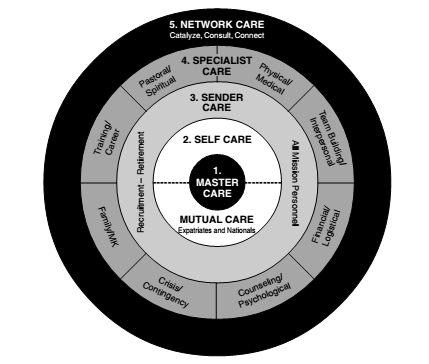

Kelly O’Donnell and Dave Pollock published a work on member care in 2002 called Doing Member Care Well: Perspectives and Practices from Around the World.’6 In this book, they present a best practice model for member care, first published in 2000, which has become a standard for member care for cross-cultural workers (Figure 1). 7

Figure 1: A Best-Practice Model for Member Care by Kelly O’Donnell and David Pollock

In their model, they divide care into five major spheres according to the care providers presented as a series of concentric circles. The first sphere of care is called master care. This is the ‘heart’ of member care. This refers to the cross-cultural worker receiving care from the Lord through his personal relationship with Him. Master care is fundamental to our well-being. It is important to note that our ministry flows out of our relationship with the Lord (2 Pet 1:5-8).8 There is a ripple effect from the centre to the outlying concentric circles.

The second sphere of care comes from self-care and mutual care. Self-care refers to taking care of one’s own life (1 Tim 4:16 NIV). This includes spiritual, intellectual, emotional, physical, and inter-relational health. Mutual care refers to the care we receive from each other in the body of Christ (Rom 15:5, Gal 6:2, 1 Pet 4:10). It could be from the local body of Christ, fellow team members, the wider missionary community, or spiritual mentors (at home or on the field).

The third sphere of care comes from the senders, which include mission agencies, sending and supporting churches, and special homeside support groups for member care.9 From the mission agency’s perspective, it will include all mission personnel related to the worker from recruitment to retirement. We will be focusing on this particular aspect in the rest of this article.

The fourth sphere of care is called specialist care. It relates to the involvement of specialists in providing professional care in different areas of the member’s need, which are beyond the ability of mission personnel. These may include medical care, pastoral counselling, psychological counselling, debriefing, financial planning, team/interpersonal relationships, training, family/TCK care, crisis /contingency care, etc.

The fifth sphere of care is called network care. It relates to connection, consultation, collaboration, and catalyzing between different agencies/networks to help provide and develop strategic and supportive resources for issues related to the wider missionary community. A good example would be that of the World Evangelistic Alliance (WEA) Mission Commission, which has produced much research material on mission-related topics and missionary needs.10 Apart from Too Valuable to Lose, WEA has also published Worth Keeping to look at the wider issue of missionary attrition and how to prevent it.11

Sender Care from an Agency Perspective

1. Prayer Support

Missions have their root in prayer. Missions must have prayer in all of its plans, and prayer must precede, go with, and follow all cross-cultural workers. This is especially so for those serving in the DPRK with their many challenges. The history of missions shows an inextricable link between intercessory prayer and the progress of the gospel. According to the late Robert E. Speer, ‘Deeper than the need for men, deeper than the need for money, deep down at the bottom of our spiritless life is the need for the forgotten secret of prevailing, worldwide prayer.’12

Thus, encouraging the prayer life of the workers, facilitating their communication with personal prayer partners, providing prayer resources to raise up more prayer partners, and forming prayer groups for the DPRK have been a vital part of member support for cross-cultural workers in the DPRK. Prayer helps our workers to depend solely on God for their ministries. It also helps to involve many more in the work in the DPRK through prayer. On the field, this can be seen in regular prayer letters to prayer partners, team prayer meetings, monthly team prayer updates, days of prayer, and community prayer meetings. Up-to-date prayer resources have also been made available regularly to the Christian public to encourage more informed prayers for the DPRK. Since 2005, we have seen the formation of prayer groups for the DPRK in a number of countries in Asia, Europe, and the Americas. Our desire is to see a worldwide prayer movement for the people of the DPRK, and to see the work and workers in the DPRK be covered over and propelled forward by the prayers of many.

J. O. Fraser, missionary to the Lisu people, said, ‘I believe that it will only be known on the last day how much has been accomplished in missionary work by the prayers of earnest believers at home. Solid, lasting missionary work is done on our knees.’13

2. Care in Selection of Workers

The work in the DPRK is not for novices. It requires workers with a clear call, spiritual maturity, physical well-being, emotional stability, cross-cultural intelligence, a servant spirit, living an incarnational life, willingness to work in a team, integrity, ability to focus, and above all, resilience.

Hence, good member care begins with the thorough selection of suitable workers. We need workers who are called, skilled, and willing. We recognise that it is the Lord of the harvest who calls, prepares, and sends out his workers (Matt 9:35, 36). In partnership with him, we help the candidate to listen well to the Lord’s guidance, to see how he has been working in their lives and equipping them for meeting the needs in the DPRK, and to reflect on whether there is a good alignment with our organization/team’s vision, mission, belief, and values.

We encourage each applicant to visit the field and go on a short term trip inside the DPRK before they make the decision for long-term service. This allows them to have a realistic idea and healthy expectation about life and work inside the DPRK. They benefit greatly from interacting with field workers and others in the wider community. It also allows us to get to know them and for them to get to know the team and our ministry approach. We also partner with the church in the selection of candidates by seeking feedback from them and involving them in interviews. Through the application process, we seek to ensure that the right person is sent to the right place at the right time for the right ministries.

3. Medical Care

As mentioned above, physical well-being and emotional stability are necessary, especially when one is living under tremendous stress and is provided with only limited medical services such as inside the DPRK. Hence the candidates are thoroughly screened for physical and psychological health during the application process.

On the field, medical support is provided by the field medical advisor. Outside the DPRK, the field medical advisor provides day-to-day medical consultations, referrals to trusted local medical facilities, up-to-date immunisations, two-year medical reviews, medical insurance and evacuation arrangements, as well as health updates (eg SARS, Ebola virus endemic, etc.). While in the DPRK, emergency consultations and help with initiating medical evacuations can be given by the field medical advisor as required.

The field team leader is responsible for the overall welfare of each member, including their psychological needs. To prevent burnout, the leader ensures that the cross-cultural worker has regular days off, holidays, and home assignments. Members are also encouraged to take self-assessment inventories at regular intervals to check on their psychological health status.14 Unfortunately, though not unexpected, there have been a number of workers who have suffered serious physical illnesses such as cancer and psychological illnesses such as depression, and have had to be sent home for long-term treatment. These decisions are made only after consultation with the workers, their homeside medical advisor and centre leaders, their family, and their sending church.

4. Language, Culture, and Worldview Learning Support

Duane Elmer asked people around the world how they felt about cross-cultural workers. This was their response. ‘Cross-cultural workers could be more effective if they did not think they were better than us.’ In order to be a good cross-cultural servant who understands, accepts, and identifies with the local people, one needs to learn about them, with them, and from them.15

To this end, all new workers must complete the Language, Culture, and Worldview Training (LCW Training) phase before they can be designated to ministry in the DPRK. This identification with the local people and the living out of a life reflecting Christ (incarnational ministry) are crucial in the DPRK where one does not have the freedom to share the gospel. LCW Training is an integrated approach to culture, language, and worldview learning for incarnational ministry. Our vision is to see our members at home in their host culture, effectively relating to and serving alongside their focus people, performing with competence in culture and language. It is hoped that members will not be just surviving, but thriving in the host culture, and be effective and productive in their ministries.

During this phase, they will be supervised by the LCW Training Coordinator, an expanded role from that of the language supervisor, who facilitates learning and provides personal support for each LCW Learner. He coordinates teaching personnel, advises about learning institutes and learning material, conducts meetings for culture learning/case studies/research projects, and provides regular LCW assessment. He or she also meets up with each LCW Learner regularly for support and encouragement, and gives advice on how to improve their learning, including arrangement for language exchange or attendance at local churches/meetings. He also coordinates opportunities for learning the spiritual language.

Members are encouraged to adopt a lifelong learning attitude. After entering the DPRK, members will continue with language, culture, and worldview learning on the ground.

5. Team Support

The cross-cultural worker is not a superhero or a lone ranger. No cross-cultural worker can do all the work by himself/herself. Together with others, we each achieve more (Ecclesiastes 4:9-12, NIV). This is especially so in the DPRK where the challenges and obstacles are overwhelming, and there is much to gain by working with and learning from more experienced workers in a team setting. Hence one of our values is to work as a healthy multicultural team. This includes integration into the team, bonding as a team, and playing one’s part in building a healthy team. Just as one values the team and gives to the team, so one will receive from the team the support one needs in serving in the DPRK.

After attending an international orientation course at our headquarters, new workers arriving on the field will undergo a New Workers’ Orientation Course (NWOC). This field orientation course introduces them to the team’s history, structure, function, members’ commitment, ministry approach, introduction to the DPRK and CN, finance matters, security and communication guidelines, LCW Training, health and stress management, partnership, etc. The new member also signs a team agreement and agrees to give accountability to the team leadership. It is hoped that a better understanding of the team and member’s roles will foster each member’s sense of belonging and commitment to the team.

Bonding with the team takes place through regular team meetings and an annual field conference. There is also the informal interaction with one another during the week and on special occasions. It is most important to establish a team where the members are constantly praying for the team and for one another. The goal is for each member to nurture strong and healthy relationships within the team. This will facilitate the giving and receiving of mutual care. Members are encouraged to use their spiritual and natural gifts to serve the team. It may only involve serving over a short period to meet a specific need for the team or for individual members. It is the team leader’s role to ensure that all members are given opportunities to be involved in serving the team. It is the member’s role to make themselves available to serve the team and one another when needs arise. In this way, a healthy team is formed.

Working in a multicultural team requires much hard work. Language, cultural, and worldview differences can easily give rise to misunderstanding, confusion, and even conflict. However, a well-working multicultural team is a most beautiful and compelling testimony of the power of the gospel to break down the barriers between different ethnic groups.16 It will speak to the hearts of the people in the DPRK to see Caucasians, Koreans, Chinese, and Japanese people become Christians and work together as a team for the Lord.

6. Leadership Support

The team leader plays a significant role in providing pastoral care for each member as well as holding the member accountable for his/her life and ministry. Apart from regular team meetings, there should be frequent contact and interaction between the team leader and the member. Thus, there is always an open channel for the member to communicate his/her needs to the leader and for the leader to observe how the member is doing in life and in ministry.

The team leader with the leadership council plays a significant role in guiding the field placement process of post-LCW Training workers. This includes consideration on where to serve, what kind of ministry, and which project/business team to join. This is a consultative process over a number of months at the latter part of the LCW Training phase. The member will take initiative to find out more about what is available and where the needs are. The team leader will then make contact with the potential project team leader to understand the set up and management of the project/missional business, and how the team functions. He also needs to ascertain a good alignment of vision, mission, belief, values, and especially financial values and financial management.

The members should provide a regular report on their ministries, whether it is a project or missional business or education. This is part of the member’s accountability to the team. This will also allow opportunities for the leader to give input and help as the need arises. After each trip inside the DPRK, it will be beneficial for the member to touch base with the leader for updating ministry progress and sharing about experiences while in the DPRK that might have caused concern. For those teaching at universities, it will require a longer time for debriefing to take place after the member has settled back into normal life outside the DPRK after a semester.

Once a year or every two years, there should be a formal review of the member’s life and ministry. The review includes physical well-being, spiritual life, emotional health, intellectual development, family, parent-children relationships, financial support, friendship, LCW Training, ministry effectiveness, home assignment planning, etc. This is to allow the member time to reflect, to share about concerns, to receive advice on how to resolve problems, to set development goals, and to plan for future ministries. This is also part of the member’s accountability to the team.

In rare situations, when the team member is not performing accordingly or refuses to submit to leadership or disagrees with the team’s agreed VMBV or has committed a misconduct, the team should have a clear disciplinary policy and process. Depending on the seriousness of the situation, this may include temporary cessation of ministry, counselling, or in the worst scenario, dismissal if it is a serious misconduct, a criminal offence, or if the disciplinary process is not followed through by the member.

7. TCK Care

In recent days, we have seen more families with young children living inside the DPRK. A number have now gone back to their own countries to pursue college studies. Missionary Kids (MK) or Third Culture Kids (TCK) are part of the cross-cultural team. A family‘s stay on the field is dependent on how their children are settling and doing on the field. It is a fact that many workers left for home prematurely because their children did not settle well on the field.

Thus attention needs to be given to the needs of the accompanying children. This begins with the application process, where a proper assessment of the children’s psychological well-being should be carried out by professional counsellors. The homeside TCK Advisor will also assess the family dynamics, give advice about the children’s preparation to go to the field, and the planning for their education on the field.

The field TCK Advisor will give special attention to how the children are adjusting to the new environment and the new education arrangement. Special home help may need to be given to the family during the LCW Training phase as the parents will be under a fair amount of stress. The field TCK Advisor will keep in regular contact with the parents about schooling options and the children’s progress. Occasionally, the parents may need special help with children who are struggling with the field environment or with learning difficulties. Provisions should be made for children’s programmes during team meetings, field conferences, and training events so that families can fully participate in these important team activities.

Presently, most parents inside DPRK have chosen to homeschool their children. This is because there are not many options. However, not all parents are capable or confident of homeschooling their children. It is a big challenge to be a good homeschool teacher and a parent at the same time. The field TCK Advisor provides support to the parents and also helps in seeking suitable TCK teachers to come. He/she may also coordinate occasional community school weeks for TCKs and their parents to address the downside of homeschooling. This relates to the children being isolated from other children and the lack of group activity opportunities with other children. Parents who decide to use boarding school in another country will need special help in preparing their child for school and going through the separation from their child.

8. Finance Support

‘Without money, there is no mission.’ Most cross-cultural workers would prefer to do ministry rather than looking after their finances. Nevertheless, they need to be good stewards of the funds given by their supporters and sending/supporting churches. In the work in the DPRK, most members are involved in projects or missional businesses which require good financial management and faithful reporting to donors or investors. They also need to fulfill stringent legal requirements by both the home country and the DPRK. Thus good financial planning and management services are a great support to cross-cultural workers.

The field financial manager is responsible for overseeing the finance management of the entire field team as well as assisting individual members. His/her roles include annual budgeting, allocation, payment of allowance and expenses, regular reporting, and external auditing. The annual budget for members includes all the expenses needed for the life and ministry of the members and their family, that is, according to the needs. Through the organisation’s intranet, members can look up financial reports anytime, anywhere, showing their fund balances and donation details from around the world. Hence one can thank one’s donors without undue delay.

The field manager oversees the setting up of projects and its financial management and reporting back to the donors. The field manager also gives advice to those involved in missional business about proper use of funds for profitable purpose, compliance of tax laws and of sanctions by UN and individual countries. With the finance manager’s service and support, field members can be released from unnecessary administration and worries about handling finance. They can thus give more fully their time to their ministry.

9. IT Support

IT security and communication guidelines are important with work related to the DPRK. Careless mistakes can lead to detention and imprisonment, as well as impact on local people. The team IT Coordinator oversees these areas for the team. He or she ensures that members are aware of the security agreement signed by each member to use encrypted, uncompromised computer, legal, and secured software, secured emails, and to carry out regular back-up. Team members are also expected to follow communication guidelines about the use of mobile phones, social media, newsletters, web, emails, etc.

Special care and vigilance are required for those who travel in and out of the DPRK for work. Often unnecessary attention from the security bureau is the result of unintentional mistakes or blatant ignoring of the security and communication guidelines agreed on by the team. Thus the IT Coordinator updates the team regarding significant changes and keeps reminding the team about security and communication guidelines! Following agreed security and communication guidelines faithfully will protect not only the member per se, but the rest of the team as well as the work involved.

10. Training and Development Support

As people are the most important resource for the mission team, it is not surprising that one of our organisational values is life-long learning. Therefore, we intentionally provide members with opportunities to receive training and development so that they can give their very best to the work of the Lord (1 Cor 15:58).

The Training and Development Support is based on the Integrated Life and Ministry Model. Integral development refers to the development of the whole person. We want to help each other grow (1) in our relationship with Christ, (2) in our Christlikeness, (3) in our knowledge and use of God’s Word, (4) in our adapting to the language(s) and culture(s) of the people among whom we work, and (5) in the acquisition and development of those skills that will equip us for ministry and leadership. These 5 areas can be represented as concentric circles with (1) being the core. The natural progression in development is to move from the inner circle to the outer one. Growing in our life with Christ will influence our development in the other areas. Growing in Christlikeness will give us the character traits required to persevere in the other three areas. Growing in our biblical understanding should help us adapt to the culture of the people among whom we work and do our ministry in ways that please God.

All members are encouraged to take up various training and development activities with consent from the team leader. These include personal development programmes, studying e-learning modules on the internet, participating in face-to-face member development programmes (eg teamwork, evangelism, and disciple-making training), skills training (eg specific support role training), and leadership training. After one term of service, members can also apply for a study leave for longer, intensive studies such as a graduate or postgraduate programmes. There is also a central record of all the training activities that a member has undertaken since joining the team. This record will allow for easy reference for future Training and Development planning.

11. Crisis Care

Crises often come unannounced. Our ministry is not free of risks, therefore we must be wise and prepared for those major kinds of problems that can be anticipated. This is especially true for workers in the DPRK, in terms of natural disasters, detention, and medical evacuation. We must not fearfully worry, but have foresight. What is a crisis? It is basically a change in our situation that threatens our ministry (in a broad sense), and it usually requires some kind of action as a response.

What kind of crisis can develop within the sphere of work with and in the DPRK? A collection of situations and threats can cause a major crisis (Table 2). These can be divided into the following 5 categories—environmental risks and natural disasters, political and social events, criminal and related issues, ministry related issues, and personal issues.

Table 2: Situations and threats that can cause a major crisis

1. Environmental Risks/Natural Disasters

- Earthquakes

- Volcanos

- Landslides

- Mud floods/flash floods

- Fire/smoke/haze

- Extended Droughts

- Pandemics/breakdown of health services

2. Political/Social

- Bombings

- Coup d’etats

- Riots/civil unrest—ethnic/political/religious/economic

- Electrical/fuel/food/water shortages

- Telecommunications

- Admin/immigration (VISA/residential permits, etc.)

- Travel restrictions (likely due to EBOLA, MERS, quarantine, or GTR in Sept. 2017)

3. ‘Criminal’ and related issues

- Kidnapping/hostage taking

- Robbery/thefts/burglary

- Assaults

- Car jackings

- Murder

- Rape

- Motor vehicle accidents (MVAs)

- Extortion

4. Ministry-related issues

- Detainment/imprisonment

- Deportation/expulsion

- Slander

- House searches

- Company audits

- Local protests/commotion

- Threats (including to local colleagues)

- Damaging media exposure of ministry (hostile or friendly; field or homeside)

- Betrayal from local co-workers, embezzlement

5. Personal Issues

- Mental breakdown, burnout, psychosis

- Moral failure

- Suicide

- Natural death

- Severe illness

- Major marital/family conflicts

Each team must have a Crisis and Contingency Plan at hand, which includes policies and guidelines on how to mitigate and handle crises and communicate about them. The crisis and contingency plan should include the following:

- Defining possible crises

- How to mitigate preventable crises

- When crisis happened, how it should be communicated

- When things get worse, how do we assess the crisis: defining Crisis Category (the kind of crises) and Crisis Level (the severity of the crises—eg normal, concerning, affecting, disrupting, evacuating)

- A description of actions and preparations the team/each member must take for the different security levels in each category

- Further guidelines for the particular crisis

- Formation of Crisis Management Team and its operation guidelines

- A Crisis Checklist on things each member should absolutely do in order to prepare for a crisis; this Checklist should be regularly reviewed and acted upon

- The Crisis and Contingency Plan should also be reviewed regularly

Conclusion

Missionaries have many needs. They need divine help. They also need help, encouragement, and care from others. The sending agency, the sending/supporting churches, and individual supporters need to play their roles in providing sender care. It is only when goers and senders partner together as a united team that the gospel work will go forward and the Lord’s name will be exalted. This is especially true for the work in the DPRK.

Does member care work? According to ReMAP II, in a survey of 37,000 missionaries from 540 agencies, after 10 years, high-retaining agencies (those with good member care) still had 72% of their workers while low-retaining agencies (those with poor member care) only had 40% of their workers.17

However, it must be cautioned that there can be a ‘too much’ of member care. Members can be pampered with too much care. The team can become too much concerned about internal relationships at the expense of their ministry. Members can have unreal expectations of the support services from the agency and the team, while at the same time, fail to see their own commitment and obligation to self-care and to be an active member of the team. This will result in members who are unable to look after themselves, become risk-averse, easily give up, and leave the field prematurely in the face of discouragement, pressures, suffering, and illness.

In addition, it is a fact that, for many, suffering is very much a part of their ministry experience as much as joy and fulfillment. This is especially so in a difficult and demanding field like the DPRK. No matter how much member care is provided or how well crisis and contingency plans are made, we cannot avoid facing risks and experiencing suffering. Hence cross-cultural workers must develop a sound biblical theology for suffering before they go to the field.

Endnotes:

- Taylor, William (Ed). 1997 Too Valuable to Lose: Exploring the Causes and Cures of Missionary Attrition. Pasadena, CA USA. William Carey Library, 85-104.

- Ibid., 1, p86. Note: “unpreventable attrition” refers to regular retirement, death in service, completion of project etc. and “potentially preventable” reasons refers to personal (i.e., emotional problems, immoral lifestyle), family (i.e., children’s education, marriage problems), team (i.e., conflicts with co-missionaries), agency (i.e., financial problems, disagreement with leadership), work-related (i.e., personal dissatisfaction, lack of performance or training) and cultural reasons (i.e., unsuccessful cultural adjustment, language learning deficits).

- Johnson, Todd M., et al. 2017 “Christianity 2017: Five Hundred Years of Protestant Christianity.” International Bulletin of Mission Research, Volume 41, Issue 1. 41-52.

- Dodds, Lois., and Dodds, Larry. 1999. “Love and Survival: In Life, In Missions.” A report on Dean Ornish’s significant book and its relevance to research on stress in missions. Mental Health and Missions Conference Angola, Indiana November 16-20, 1999. Liverpool, PA: Heartstream Resources for Cross-cultural Workers.

- Ibid., 1, p91.

- O’Donnell, Kelly (ed). 2002 Doing Member Care Well: Perspectives and Practices from Around the World. Pasadena, CA USA. William Carey Library.

- Ibid., 6, p16.

- Fernando, Ajith. 2002 Jesus Driven Ministry. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press IVP, 29-46.

- Homeside Ministry Team. http://homesideministryteam.wordpress.com/ Last accessed on 29 Sep.

- World Evangelical Alliance. http://www.worldea.org/ Last accessed on 28 Sep. 2017.

- Hay, Roy., et al. 2007. Worth Keeping: Global Perspectives on Best Practices in Missionary Retention. Pasadena, CA USA: William Carey Library.

- Piper, John F. Jr. Robert E Speer: Prophet of the American Church Louisville Kentucky: Geneva Press, 423.

- Taylor, Geraldine. 1982. Behind the Ranges: The Life-changing Story of J.O. Fraser. Singapore: OMF International, 52.

- Holmes, Thomas., and Rahe, Richard. 1967. “Holmes-Rahe Social Readjustment Rating Scale.” Journal of Psychosomatic Research Vol. 11, pp. 213-218. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. 2001. “The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure.” J Gen Intern Med. 2001 Sep 16(9):606-13. Sturt, John., and Sturt, Agnes. 1994. Created for Love. Highland Books. (Burnout Preventive Assessment)

- Elmer, Duane. 2006. Cross-Cultural Servanthood: Serving the World in Christlike Humility. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 93.

- Linder, Johan. 2016. Working in Multicultural Teams. Sydney, Australia: Hudson Press.

- Ibid., 11, 197-203.