Editor's Note

This article is based on the session at the Fourth Lausanne Congress.

The Fourth Lausanne Congress took place in Incheon, South Korea in September 2024.1 This marked the 50th anniversary of the Lausanne Movement, which held its first official gathering—the First International Congress on World Evangelization—in Lausanne, Switzerland in 1974. The global landscape of Christianity has changed dramatically over the five decades since that gathering of Christians from around the globe. Many scholars, most notably Philip Jenkins, have noted that there has been a shift in the center of gravity of the Christian world from the North to the South.2 The unprecedented growth of Christianity in the Majority World has shaped the distinctively global character of the Christian faith in the 21st century.

Many participants were amazed to learn about how God has transformed this small, isolated country once devastated by war and poverty into an economically powerful, culturally influential nation that is the second largest missionary-sending country.

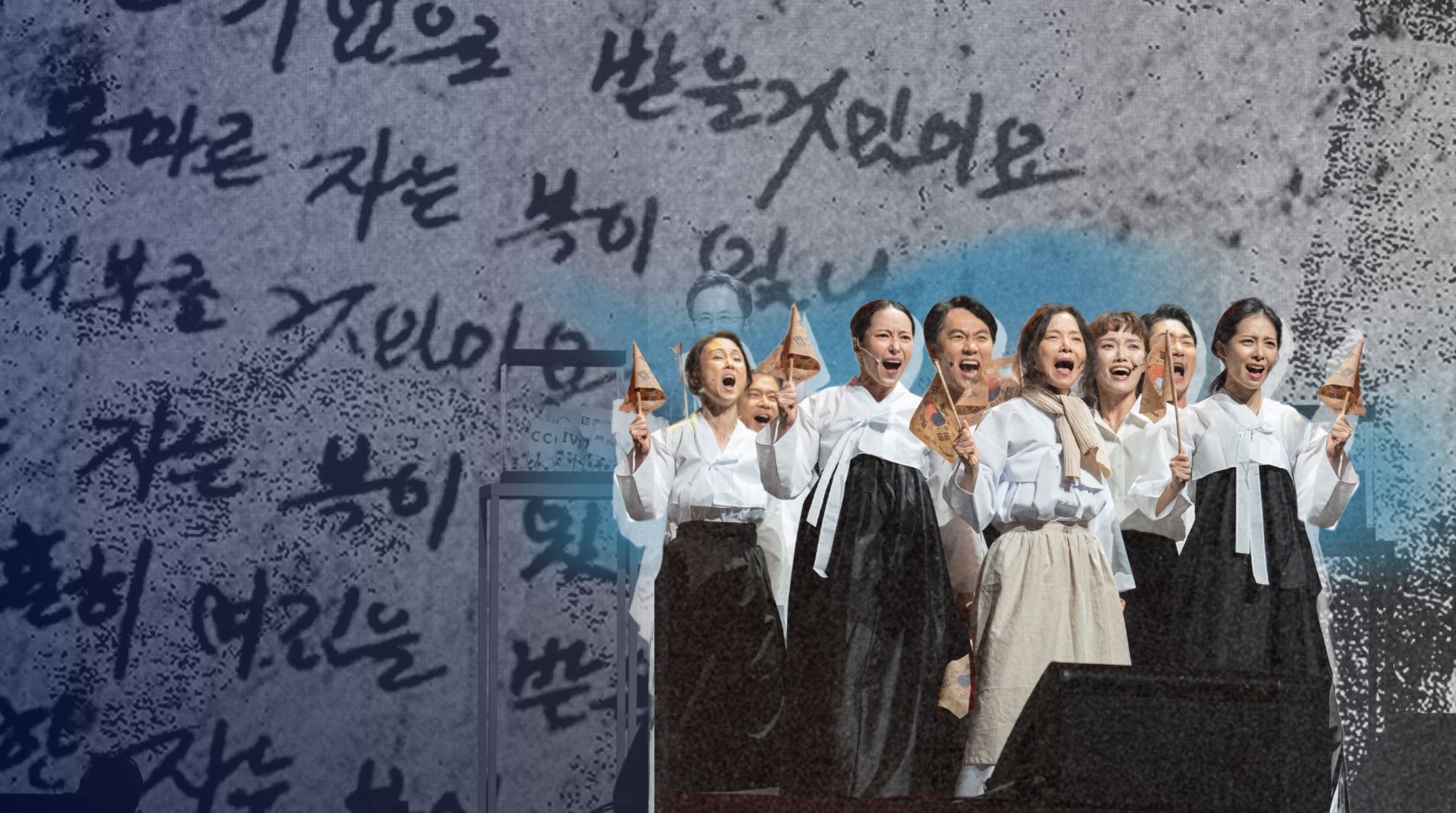

South Korea is widely recognized as one of the most important mission forces in the contemporary period. During the recent Fourth Lausanne Congress, an evening session was devoted to the history of the Korean church and lessons that can be learned from it.3 Many participants were amazed to learn about how God has transformed this small, isolated country once devastated by war and poverty into an economically powerful, culturally influential nation that is the second largest missionary-sending country. In particular, the delegates from the Majority World became greatly encouraged to find the actual historical example that manifests the power of the gospel to transform both individuals and society. If God has done this marvelous work in one country, he can surely do the same thing in other parts of the world.

Defining Moment: The Pyongyang Revival of 1907

It would be an exaggeration to argue that a single historical event shaped the character of the Korean church. However, the Pyongyang Revival in 1907 certainly was a profound factor. Historically, it was not an isolated single event; it was part of a series of revivals in the Protestant churches of Korea from 1903 to 1910.4 At a time of national crisis—wars and famines—the first spark of the revival movement was ignited in Wonsan in 1903 under Methodist missionary Robert A. Hardie. The movement soon expanded to the Presbyterians in 1906.

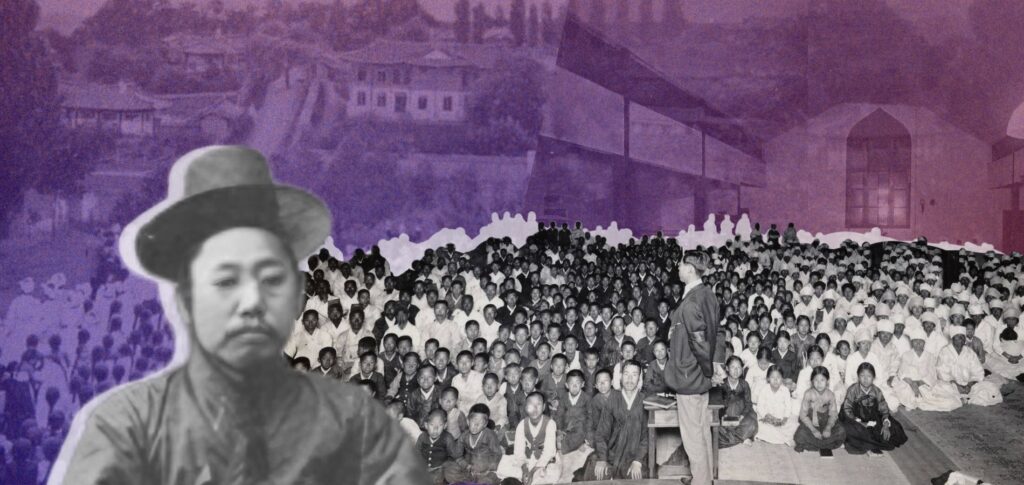

The Pyongyang Revival reached its peak during a Bible class at Central Presbyterian Church in Pyongyang in January 1907. Those who were present sensed the presence of the Holy Spirit and felt an extraordinary conviction of sin; they began to repent in public for personal sins such as stealing, adultery, polygamy, and idolatry. The primary leader of the Pyongyang Revival was not a Western missionary, but a Korean pastor named Sonju Kil. He later became one of the key leaders of the March First Independence Movement in 1919. The consequences of the revival were so obvious in Pyongyang’s churches and neighborhoods that the city was called ‘the Jerusalem of the East’.

The Pyongyang Revival has had lasting impact on Christianity in Korea in several ways.5 First, the revival emphasized that believers must experience inner transformation. Since then, becoming a Christian in the Korean context has meant much more than intellectual agreement with Christian doctrine; it is understood that coming to faith involves a personal experience of conversion. Second, the revival entailed significant social changes promoting equality and reconciliation. Korea’s traditional strict boundaries of social class and gender became blurred, and Western missionaries began to perceive Korean believers as co-workers for the gospel, not merely as people who needed paternalistic guidance. Third, the revival popularized practices such as dawn prayer meetings, collective audible prayer, and Bible study meetings. These revivalist practices are now features—one might even say the foundation—of almost all churches in Korea, regardless of denomination and tradition.

Korean Evangelicalism: From Revival to Mission

Evangelicalism is a diffuse term, not an ideology or doctrine. It commonly refers to an experiential, dynamic, and interdenominational Christian movement rooted in two 18th-century religious revivals: the Great Awakening (associated with Jonathan Edwards) and the Evangelical Revival (associated with John Wesley). Today, despite distinctive differences in theology and practice, evangelicals define themselves as Christians who regard the Bible as the ultimate authority, emphasize a conversion experience and a spiritually transformed life, and promote mission and evangelism for the salvation of others.6

The history of Christianity has demonstrated that there is a direct correlation between revival and mission.

The history of Christianity has demonstrated that there is a direct correlation between revival and mission. Revivals provide rationales and energy to bring the gospel to those who have never heard of it. Renowned historian Andrew Walls has called the modern missionary movement ‘an autumnal child of the Evangelical Revival.’7 Other examples in Christian history include D.L. Moody’s evangelistic campaigns and the rise in Britain and the United States of student mission movements. There are examples in the Korean church too.

In 1907, the year of the Pyongyang Revival, another benchmark event took place in Korea: the first Korean Presbyterian ministers were ordained. There were seven, all of them graduates of the Theological Seminary in Pyongyang. One was Sonju Kil, the most notable proponent of the Pyongyang Revival. Another, Kipoong Lee, volunteered to become a missionary to Jeju Island off Korea’s southern coast. He founded the first church on the island and his preaching of the gospel reached people well beyond its borders geographically and culturally. ‘The Presbytery of Korea unfurled its blue banner to the world as a missionary church,’ reported American missionary William Reynolds.8

In 1909, the Presbyterian Church ordained a second group of Korean ministers. Among the nine, Kwanheul Choi was commissioned as a missionary to Vladivostok, Siberia. In the following year, the Korean church launched the ‘Million Soul Movement’, a nationwide evangelistic campaign whose goal was to evangelize one million people for Christ. In 1912, when the Presbyterian Church in Korea officially established its General Assembly, the denomination sent three Korean ministers to Shandong, China, the birthplace of Confucius—a symbolic proclamation of Korean Presbyterians’ missionary character.9

Youth Mission Movements

After its period of democratization and industrialization in the 1970s and 1980s, South Korea saw a remarkable emergence of evangelical youth mission movements. Through massive evangelistic rallies, including the historic Billy Graham Crusade of 1973, the Korean church was spiritually empowered once again. In the late 1980s, deeply inspired by the comprehensive nature of God’s mission as laid out in the Lausanne Covenant of 1974, young Korean evangelicals became drawn to the divine calling to serve the kingdom of God beyond their own social, cultural, and geographical boundaries. They were willing to go wherever the Holy Spirit led in order to proclaim and demonstrate the power of the gospel to bring about the holistic change of individuals and society.

The pinnacle of the youth mission movement was Mission Korea Congress, a biennial missionary convention for college students and young adults. It was established in 1988, the year of the Seoul Olympic Games. In the decades since then, Mission Korea Congress has served as a major impetus to empower and mobilize numerous young evangelicals for global mission. The number of attendees grew dramatically—from 664 in 1988 to 6,300 in 1996.10 More than half of the people who attended the Congresses in that period committed themselves to foreign mission. With the influx of young missionary candidates, the number of Korean missionaries increased rapidly from 511 in 1986 to 10,422 in 2002. It took only eleven years more for the number to reach 20,000.11

Several factors have contributed to the dramatic growth of Korean missionaries. First, Korean Christians hold Scripture in high regard.12 They consider the Bible to be the only and final authority for life and faith. There is very broad acceptance of the claim that the Great Commission is the highest calling to all disciples of Jesus. Second, the Korean church maintains a tradition of generous and sacrificial giving, especially for the cause of mission.13 The first Protestant church in Korea, Sorae Church, was built by Korean Christians’ contributions. American missionary Horace G. Underwood was astonished to see what huge sacrifices disadvantaged Koreans made in order to donate to churches and Christian missions.14 Third, practical issues, such as economic growth and diplomatic ties with almost every nation, help Koreans conduct missionary activities around the world. According to the Henley Passport Index, South Korea ranks third on the 2024 ‘global passport power list’15: someone who holds a South Korean passport can travel visa-free to 191 other countries.

Challenges and Future Prospects

For the past two decades, however, the Korean church has experienced stagnation and even decline. The reasons include secularization, young people’s increasingly indifferent attitudes towards religion, and scandals in several megachurches.16 Korean society’s confidence in the credibility of the Korean church has declined as well. Some keywords used to characterize Korean Christianity are ‘exclusive’, ‘materialistic’, ‘hypocritical’, and ‘selfish’. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic brought serious challenges to churches in Korea. During and after the pandemic, many churches struggled as weekly worship service attendance declined and fewer people participated regularly in other ministries. The resulting drop in financial donations left some churches unable to maintain their previous level of support of missionaries serving overseas.

In preparation for the Fourth Lausanne Congress, influential Korean pastors such as Jaehoon Lee and Kisung Yoo called on Christians to pray for repentance and revival in the Korean church. In July 2023, 10,000 Christians from 430 churches across denominations and regions gathered together at Songdo Convensia, the venue where the Fourth Lausanne Congress later took place, to pray for that upcoming Congress and for the revitalization of the Korean church. The participants unanimously affirmed that the Congress would mean nothing to Korea without united prayer for the spiritual renewal of individual believers and churches. They committed themselves to pray every day for each nation that sends representatives to the Congress. Within Korean churches, this grassroots prayer movement was key to promoting and publicizing the spirit of the Lausanne Movement.

The leadership of the Korea Lausanne Committee stressed that the Fourth Congress ought not to be a time for the Korean church to celebrate its missional achievement before the global church. Instead, it should be a time for Korean Christians to reflect, repent, and learn from the global body of Christ. This attitude shaped the transparent, honest, and humble tone of the Korean presentation during the Fourth Congress. Korean church leaders no longer assert that the Korean church will and should play a pivotal role in fulfilling the Great Commission. As the Cape Town Commitment rightly notes, ‘No one ethnic group, nation, or continent can claim the exclusive privilege of being the ones to complete the Great Commission’ (CTC II-F 2).17 Global mission belongs to the sovereignty of God; we are simply earthen vessels to show the all-surpassing power of God in making all things new by his grace.

Endnotes

- Editor’s Note: This article is based on the session at the Fourth Lausanne Congress.

- Philip Jenkins, The Next Christendom: The Coming of the Global Christianity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002); The New Faces of Christianity: Believing the Bible in the Global South (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006).

- The presentation about the Korean church during the Fourth Lausanne Congress can be viewed on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U5yzpFbWgeI&t=3636s

- For a historical overview of Protestant revivals in Korea in the early 20th century, see Sung-Deuk Oak, ‘Major Protestant Revivals in Korea, 1903–1935,’ Studies of World Christianity 18, no. 3 (2012): 269–290; The Making of Korean Christianity: Protestant Encounters with Korean Religions, 1876–1915 (Waco: Baylor University Press, 2013), 271–304.

- Sung-Deuk Oak, The Early History of the Korean Church (Seoul: Jidda, 2016), 314–327.

- For a historical analysis of global evangelicalism, see Mark Hutchinson and John Wolffe, A Short History of Global Evangelicalism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

- Andrew F. Walls, The Missionary Movement in Christian History: Studies in the Transmission of Faith (Maryknoll: Orbis, 1996), 79.

- W. D. Reynolds, ‘The Presbytery of Korea,’ Korea Mission Field 3, no. 11 (Seoul: Evangelical Missions in Korea, 1907), quoted in Timothy Kiho Park, ‘Korean Christian World Mission: The Missionary Movement of the Korean Church,’ in Missions from the Majority World: Progress, Challenges, and Case Studies, ed. Enoch Wan and Michael Pocock (Pasadena: William Carey Library, 2009), 100.

- Park, ‘Korean Christian World Mission,’ 100–101.

- Daehaeng Lee, Mission Korea 8818+3 (Seoul: Mission Korea, 2022), 8.

- Steve Sang-Cheol Moon, The Korean Missionary Movement: Dynamics and Trends, 1988–2013 (Pasadena: William Carey Library, 2013), xix.

- Timothy Tennent pointed out five major trends in the theology of Majority World Christians: 1) high regard for Scripture; 2) moral and ethical conservatism; 3) sensitivity to issues of poverty and social justice; 4) ability to articulate the gospel in the midst of religious pluralism; 5) appreciation for the corporate dimensions of biblical teachings. Timothy C. Tennent, Theology in the Context of World Christianity (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2007), 14–15.

- Moon, The Korean Missionary Movement, xx.

- Oak, The Early History of the Korean Church, 300–302.

- The Henley Passport Index, https://www.henleyglobal.com/passport-index/ranking, accessed November 8, 2024.

- Isabel Ong, ‘South Korea’s Missions Success Won’t Be Its Future,’ Christianity Today (September 17, 2024), https://www.christianitytoday.com/2024/09/south-korea-missions-aging-missionary-christian-lausanne.

- The Cape Town Commitment, https://lausanne.org/statement/ctcommitment.