A group of grandmothers gather together to study the Bible, pray, sing, and fellowship. They meet once a month to encourage one another and to share the good news of Christ with the new ladies who are brave enough to attend. This is not your typical Bible study. It is special because this particular group consists entirely of Muslim-background followers of Christ. They have no previous Christian education, and some cannot attend Christian gatherings regularly because of the pressures the society imposes on them. They are supposed to be teaching their grandchildren the Islamic ways but here they are, enjoying the presence of the Lord and one another in a humble Uzbek home.

This is not your typical Bible study.

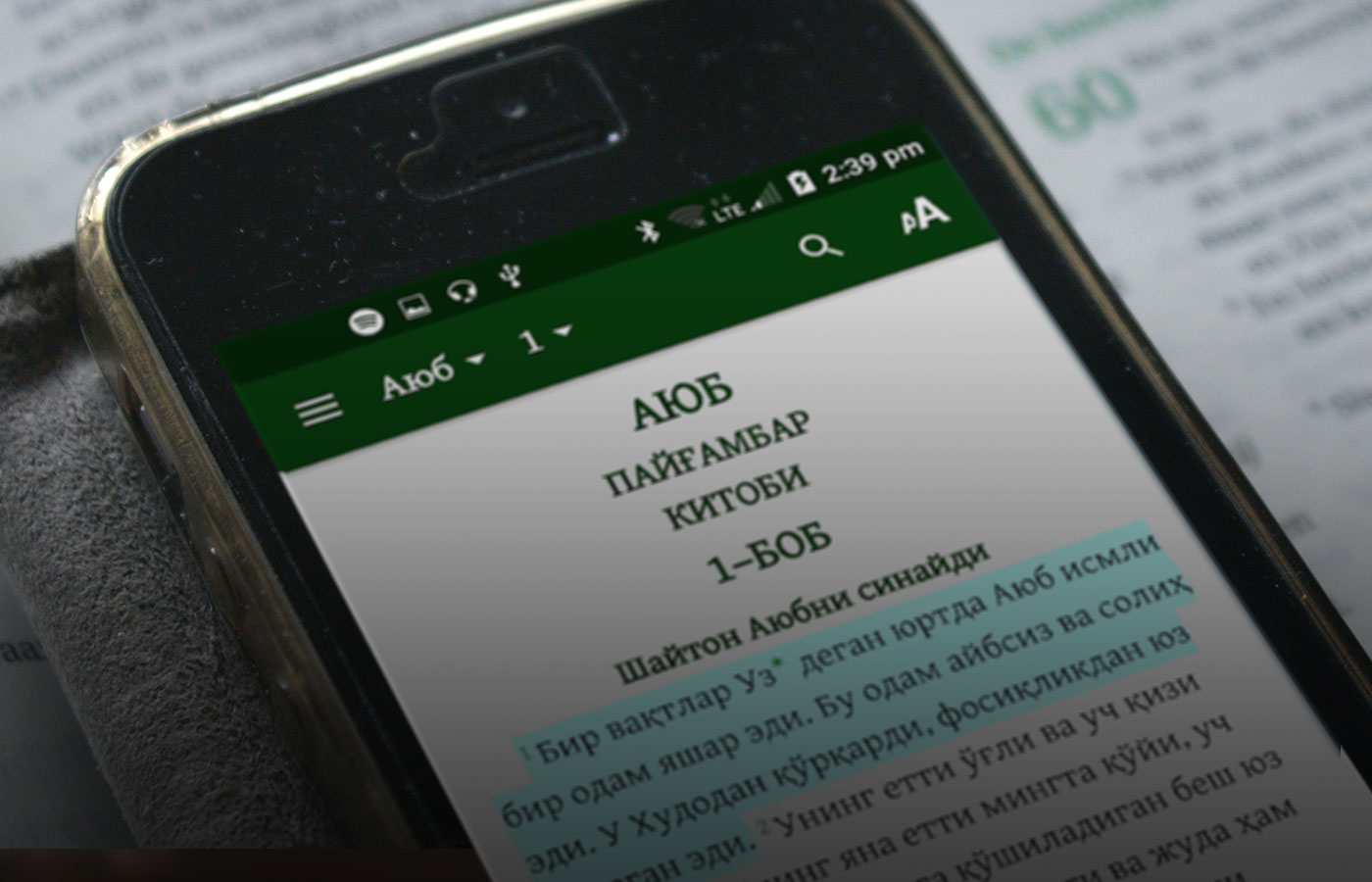

They are seated on the floor, around the tablecloth full of tasty food that Esther [not her real name], the daughter-in-law of the family, has so graciously prepared. One of the grandmothers starts to preach. She wants everyone to turn to a certain passage in the Bible. As Esther recalls it: ‘All of a sudden, these old ladies whipped out their smartphones and quickly navigated to the passage in the Bible. They didn’t miss a beat!’

The extraordinary fact is that most of these ladies probably never even had a landline, let alone a computer. They have bypassed the era of email, non-smart cell phones, and even land postal service in some rural areas. Precisely for this reason are smart phones popular. They let the isolated people stay connected. The modern texting, call, and video-chatting apps do not use much bandwidth; therefore they are accessible even in the remotest regions of the country.[1]

Uzbek Bible app

This country is Uzbekistan, which has a population of 32 million. The Uzbek language has approximately 33 million speakers, most of whom live in Uzbekistan and surrounding Central Asian countries. The Uzbek Bible app has been praised for its user friendliness:

- The interface is interchangeable between Uzbek, Russian, and English.

- The font can be adjusted by zooming with fingers and will adjust to fit the screen.

- One can highlight, take notes, copy, and share passages, and search for words or phrases easily.

- The settings are not difficult to adjust.

A significant feature the app offers is the option for the reader to transition between Roman and Cyrillic scripts (for iOS-based devices the switch is within the app; for Android phones or tablets there are two separate apps with the two different scripts):

- Roman script accommodates the speakers from other countries who do not know the Cyrillic script and the younger generation who were educated in the former.

- Cyrillic script is attractive to the older generation who grew up using it.

![]()

Uzbek app icon

All of the above-mentioned features make the app popular among people with diverse ages, education, and literacy levels. The attractiveness of the design is evident in the first look at the icon that represents the application. A picture of an Uzbek man’s hat is used for the icon and it is easily recognizable. It is also not off-putting as some religious symbols might be.

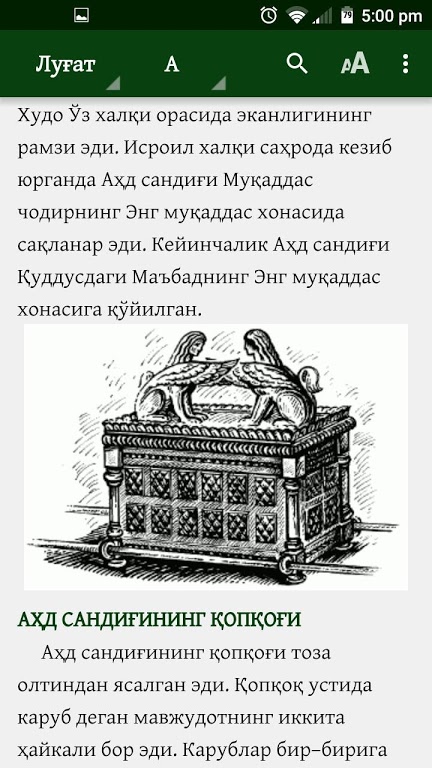

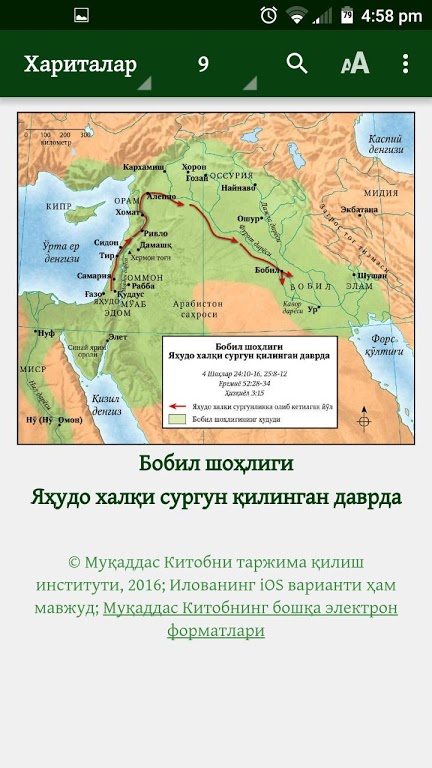

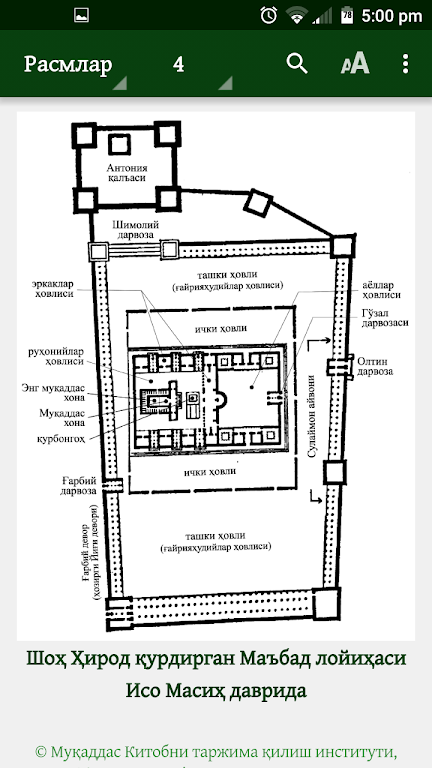

In addition to the Bible text, the Uzbek Bible has over 7000 footnotes and a glossary, with about 80,000 study links along with pictures, maps, photos of manuscripts and schematic drawings of the temple.

Impact

One should not rely on the number of downloads in order to garner statistics or measure usage as this may not be a true indication of the use of the app. Although there have been more reforms than many citizens could have imagined, the oppression of religious activity is still very real in Uzbekistan:

- This causes some people to uninstall religious apps when they do not want the authorities to find them on their phone, particularly when they are crossing the border either by land or by air. They will later download and install whichever application they would like again.

- Another trend is the use of the app, ‘Shareit’, which relies on a Bluetooth connection rather than the internet. This enables users to share apps, and the owners of the apps do not see this activity as ‘download’.

Thus tracking the usage of the app is difficult because of the particular circumstances. The actual numbers of true users could be much higher or much lower than the statistics show.

There are situations where obtaining an actual physical copy of the Scriptures is simply impossible.

The need

However, this should not deter programmers from making and distributing such apps. There are situations where obtaining an actual physical copy of the Scriptures is simply impossible, either because of geographical distance or the limited number of copies of the printed material. In the context of Uzbekistan, it is both. One can legally buy a copy of the Bible at the Bible Society of Uzbekistan (BSU) which is in the capital city. Travel to the city is not possible for many people for a variety of economic or logistical reasons. These people rely on friends and acquaintances to get them a copy. This is only possible if the friend travels to the capital often and has acquired one for himself or herself already— because of a BSU policy that only one Bible may be purchased per visit to the shop, some may not be able to buy more than one copy if their stay in the capital is too short to go to the BSU for copies on different days.

A preliminary app for the Uzbek Bible was released in 2013 for devices that use an iOS platform. This was a full three years before the first full Uzbek Bible was printed. An Uzbek Christian man took the initiative to develop an app but at the time lacked the resources to make it fully functional. The team, aware of the great need for such a tool among the community of believers in Christ, provided him with the unfinalized text for this purpose. After the Bible was published the translation team dedicated time and energy into releasing the published Uzbek Bible in electronic form. Using a program known as Scripture App Builder developed by SIL workers in Africa, the team was able to build a powerful and user friendly app that makes all the materials in the Uzbek Bible available for use on both Android and iOS phones. Scripture App Builder is a significant tool, which is being utilized all over the world to help teams with relatively basic computing skills create high quality Scripture apps for their language communities. The more complete Uzbek Bible app was released in 2017. It has the capability of playing audio files, which will be added to the app once the recording of the Uzbek Bible is completed.

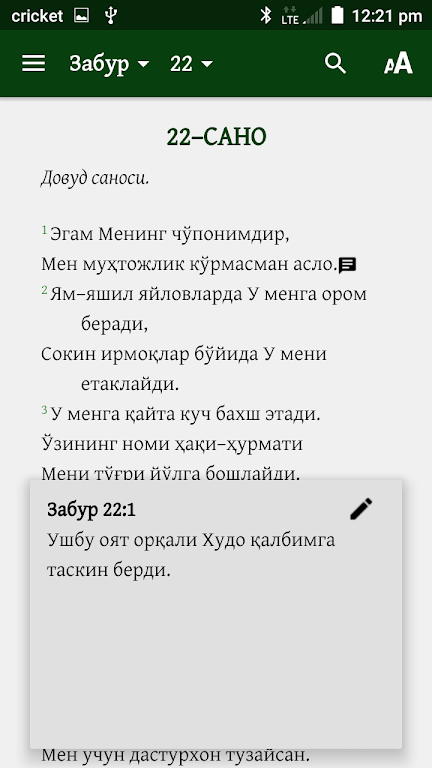

![]()

Holy Book app icon

Holy Book program

There is also a program called the ‘Holy Book’ that The Institute for Bible Translation in Moscow has developed for those who have computers. It is a Bible study program, which can be used to study the Bible in depth because the program gives the user access to original languages; it has a Word-study option, and it is updated quite regularly. Best of all, it is free. Many people in the area of the former Soviet Union are fluent in at least two languages and are able to converse in a few more. So, the option of having many different translations that can be downloaded and installed as modules is very much appreciated. It gives the user the ability to study the Bible more deeply than they can through a simple app on a phone.

A blessing for the church

Although some Uzbek people are bilingual, there are many who do not read in the other languages very well. They have expressed their gratitude for an app that is easy to use, especially for a beginner and for the chance to read the Bible in their mother tongue.

The existence of the Bible app in Uzbek has been a great blessing for the Christians in Uzbekistan and the Uzbek church worldwide.

The existence of the Bible app in Uzbek has been a great blessing for the church, not only those groups (such as house churches) in Uzbekistan but the Uzbek church worldwide. There is a diaspora of about 50,000 Uzbeks in the US and close to two million in Russia, mostly migrant workers. Besides using the app for their personal growth in faith, the believers are able to share the Bible with anyone who shows an interest in reading it without any restriction and with just the click of a button.

Global use of apps

Beyond Uzbekistan, apps are being used worldwide for what in the Bible translation world is called ‘Scripture Engagement’ and more. The story at the beginning of this article is an example of ‘Scripture engagement’. This very common term in the Bible translation world might be a foreign concept for some people. Scripture engagement aims to introduce the content of the Bible along with the biblical worldview and biblical concepts to the reader/listener.

Often these Bible apps come with an audio version or will have one added as quickly as possible. This is because many minority languages do not have much of their own literature in written form, and speakers of these languages may not be familiar with reading texts and/or prefer to relay information orally. There are many cultures which are referred to as ‘oral cultures’ and not all of them are necessarily minority people groups.[2] Uzbek culture is known as an ‘oral’ one, despite having had written literature for hundreds of years and more than 30 million speakers. Scripture engagement helps to make sure that the translations of the Bible are being put to good use rather than ignored; and the role of Bible apps is vital in this regard.

Access to the Scriptures in electronic form is a tremendous asset to diasporas. For Christians abroad it is an easy way to access the Bible in their own language.

Diasporas

Access to the Scriptures in electronic form is a tremendous asset to diasporas. For Christians abroad it is an easy way to access the Bible in their own language, not only for edification and evangelism but also for keeping their native vocabulary, pronunciation, and other language skills at a good level. I mention vocabulary specifically because it is a common phenomenon among migrants, especially second-generation speakers, to be proficient in speaking and comprehension at what might even be considered a higher-than-average level. However, in most cases, their vocabulary is not rich enough to express longings of the heart or the fears and joys of life in the language of their parents’ homeland.

This creates a sad divide between generations. The inability to communicate feelings might cause misunderstanding or create a rift that could be hard to repair as the widening distance between communication-levels increases. In this age of information, many migrant parents are understanding this issue and are taking preventative measures. One of those is the use of the biblical text which sometimes is the only written text they have access to.

A story from a Christian migrant shows how important it is to his family in their walk with the Lord to have the Bible in their own mother tongue. Having received his very own Bible for the first time and having found out that he could share the content via an app, he sent a letter to the translation organization. In it he said that, although he and his wife had read the Bible multiple times in the language of wider communication in their new country, reading it in their mother tongue felt like they had never seen some of the text before.

Here lies the beauty of making the Bible available in electronic form to a wide range of readers—be it to encourage, exhort, and teach the church or to help diasporas not to forget their own culture or language in order to not lose the beautiful heritage they have.

Endnotes

- Editor’s Note: See article by David Yeghnazar, entitled, ‘Can Technology Help Iran’s New Believers?’, in January 2019 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis https://lausanne.org/content/lga/2019-01/can-technology-help-disciple-irans-new-believers.

- Editor’s Note: See article by Jerry Wiles, entitled, ‘Orality in the Academy and Beyond’, in May 2018 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis https://lausanne.org/content/lga/2018-05/orality-in-the-academy-and-beyond.