The third European Roma Conference in Sarajevo, Bosnia, in October, attracted 226 participants from 31 countries. It was a diverse gathering of people: Roma and non-Roma, academics and those with little formal education, pastors, missionaries, musicians, leaders, and parishioners.

Significantly, the theme was ‘Healthy Partnerships’. Practical content interspersed with real-life case studies from Bosnia, Finland, Serbia, Romania, and India illustrated the multiplication value of healthy partnerships and the danger of unequal partnerships with divergent expectations. Groups organized by countries and regions discussed their experiences, both good and bad.

Why the theme at this time and place? There are challenges in developing mutually healthy mission partnerships—a fact to which both mission history and my own observations in Southeastern Europe attest. Despite this, partnership with Roma churches and communities is vital to sharing our diverse gifts while manifesting the ‘new humanity’ in Christ.[1]

‘Roma’ is often used to encompass a broader swath of people who may identify themselves as Romani, Gypsy, Sinti, Kale, Gitano, etc.

Who are the Roma?

Most scholars link those who today identify as Roma with groups of people who migrated out of Northwest India over a thousand years ago. Roma simply means ‘Romani people’ in the Romani language; this term gained more widespread use in Europe after the first 1971 Romani Congress in London since terms like ‘Gypsy’ have pejorative connotations in some contexts. Today, ‘Roma’ is often used to encompass a broader swath of people who may identify themselves as Romani, Gypsy, Sinti, Kale, Gitano, etc.[2] The question of identification is complex because sometimes a group’s self-understanding is at odds with the terminology of outsiders; generally, I wait until I hear how a community self-identifies before using any term.

Too often, the Roma are portrayed in static, one-dimensional images—often connected to poverty or criminality, for example—whether they are from Brazil, France, or Romania. It is crucial to understand that the Roma are not homogenous but are different minority groups dispersed over numerous countries and continents. They may speak different languages or dialects of Romani and have various cultural and religious practices. They also have different histories with the societies where they are embedded. In Europe, for example, past centuries of harsh policies aiming to assimilate, banish, or even exterminate Roma (in World War II) continue to foster negative images of the Roma today.

However, despite these differences, some Roma Christians feel a transnational sense of identity and missional vision, extending from Europe to North and South America and even to India.[3] For example, some scholars and activists connect the European Roma to the Banjara, a large tribe of clans found in northwestern, central, and southern India.[4] Srinivas Naik is a Banjara pastor who founded Global Banjara Baptist Ministries (GBBM), which ministers among Banjara in four different Indian states through church planting, leadership training, and social work. In Sarajevo, he expressed a strong desire to connect and worship with people from his own ethnic group. He described a sense of ‘belongingness’—not only do he and his fellow Roma belong to Christ, but also to each other in terms of ethnicity and history.

Christianity continues to grow globally among the Roma, largely in Pentecostal forms.

Parallel realities

Christianity continues to grow globally among the Roma, largely in Pentecostal forms—ranging from large revivals beginning in the 1950s in France, to rapid development in Central and Eastern Europe after the fall of Communism, and the growth of churches in Brazil.[5] Academic studies in various contexts have demonstrated that Christianity contributes to rising levels of education and literacy, and decreased crime and social distance from the majority culture.[6]

However, in Europe, there are parallel realities among the estimated 10-12 million Roma:

- Although there are Roma integrated into every sphere of society, many face a grim socio-economic situation, particularly in Eastern Europe.

- Roma groups in Europe often have higher rates of unemployment, illiteracy, and health issues, as well as substandard housing and lower education levels.

- They face social exclusion, discrimination, and racism. Prejudice is not always one-sided—some Roma groups look down on non-Roma (gadje) or even other Roma.

- The vulnerability of the Roma in certain contexts has made them prime targets for human trafficking.

Issues of discrimination and social marginalization are not confined to Europe. Although the Roma in Brazil (made up of Calon and Rom) have been the subject of rising political concern in the last 20 years,[7] they continue to face prejudice. In India, the Banjara are often socially isolated, lacking education and economically disadvantaged. Although Banjara in Naik’s state are categorized as a tribal group which allows them more social respect, they are frequently classified as Dalits (untouchables) in other states.

The need for healthy partnerships

In light of this, I believe there are three primary reasons for Roma and non-Roma to develop healthy partnerships:

1. Kairos moment?

1. Kairos moment?

It may well be a ‘kairos moment’ in terms of global opportunity to evangelize and disciple Roma groups. In Eastern Europe, many Roma pastors have stated that now is the time for the Roma, in reference to their spiritual openness. In India, Naik relates tremendous growth in the last 20 years, after Banjara began evangelizing Banjara. He independently echoed the sentiment saying that now is the time for the Banjara; God is pouring out his Spirit among them. He asked for more partners to join them from around the world to utilize this opportunity.

2. Daunting challenges

2. Daunting challenges

This kairos moment often comes in daunting contexts in terms of the challenges and opportunities compared to the available people and resources. Discipleship is an intensive process limited by the lack of people serving. For example, Naik describes limited training for evangelists and pastors which leads to ‘weak fruit’. The issues emerging from poor communities can also be overwhelming: the need for employment and job creation, education, social and political advocacy, discipleship training, trauma healing, and theological education.

There are many examples of how partnerships have increased both the quality and quantity of mission efforts:

- In Brazil, the National Roma Support Alliance (ABRACI) was formed in 2009 to promote unity among ministries and create capacity building and contextual materials.

- Igor Shimura, a social activist and Calon pastor, noted that through both national and global partnerships they are translating the Bible into the Calon language, have planted ten churches, and have mobilized missionary congresses.

- GBBM has benefited from outside partnerships which, for example, taught them how storying five stories from the Old Testament can prepare a polytheistic culture for the gospel.

3. Need for equality

3. Need for equality

Partnership is urgently needed to encourage transformation; but the history of the Roma in many contexts necessitates an emphasis on partnership quality. In Europe, for example, even the church has historically marginalized the Roma, excluding them from baptism and sometimes deeming them incompetent to lead their own churches. Equal partnerships could therefore be a critical witness to the relational reconciliation possible in Christ. Miki Kamberović, a Roma pastor in Serbia, said that, as Roma people are just starting to rise into their identity, people are needed who are not coming with their own agenda and ideas, but who are wanting to work together for transformation of Roma communities.

Roma Networks, which organized the Sarajevo conference, is a grassroots organization aiming to network, research, and connect for the purpose of transformation in Roma communities.

Roma Networks, which organized the Sarajevo conference, is a grassroots organization aiming to network, research, and connect for the purpose of transformation in Roma communities. The emphasis on healthy partnerships in Sarajevo intentionally captured the critical need to share the body’s diversity of gifts, empower the Roma, and heal the relationship between non-Roma and Roma.

The chair of Roma Networks, Croatian Nina Jankucić, noted that they do not need people, with their actions, to make Roma think they are incapable of contributing. This is something that leaves a mark on people which they transfer onto the next generation. Healthy partnerships are about everyone bringing what they have to the table. This is part of the healing process as Roma begin to believe they have something to contribute—and as they do contribute, the watching world also has its perceptions changed.

Implications

The phrase ‘bringing what you have to the table’ raises the question: what kind of table? A roundtable ensures that everyone sees one another and has equal access to the conversation. Here are some considerations for Roma and non-Roma as they come to the roundtable:

- In light of the many false perceptions and prejudices about the Roma, learning about Roma culture and history in a particular context is key. The church has a responsibility to go beyond the one-dimensional images.

- Listening, learning, and building relationships without agendas cultivate trust. The more time devoted to relationship, the less fragile the trust. This fosters mutual honesty and feedback, necessary in light of the cross-cultural miscommunication which will undoubtedly occur. Partnerships placed in a transactional paradigm, framed in terms of those who have resources and those who lack them, miss the identity and function of the Body of Christ.

- Roma Christians need to see themselves both as contributing to and learning from the global church. A mutual exchange of theological and missional understanding ignites evangelistic fervor, enriches the church-in-context, disables ministry territorialism, and challenges ethnic barriers. For example, various Banjara ministries in India are part of a Banjara Christian Council India (BCCI), which holds joint events demonstrating unity; and ethnocentrisms between Rom and Calon in Brazil are broken down in the church.

- Equal partnerships between churches in Western and Eastern Europe (and other places) have a critical role in addressing complex social issues. For example, East-West migration in Europe rapidly increased after the fall of Communism and the subsequent EU expansion. For Roma migrants, as for others, this resulted in positive and negative outcomes:

- Although many Roma migrants integrate well through employment and family networks, the vulnerability of others leads to exploitation or difficulty in navigating new social systems.

- The poorest or those involved in crime are most often featured in the media, propagating stereotypes and societal fears.

- Churches in the West may be unsure how to help individuals reliant on begging or with low-skilled labor experience.

Humble partnership at the roundtable of Christ first leads us to this enhanced understanding of God, and then to a richer participation in his mission.

However, mission opportunity flows multi-directionally, as Roma pastors send elders to oversee new churches in the West and Roma and non-Roma begin mission projects in the East. It is a complicated issue that requires more mutual learning both to seize the missional opportunities and address the challenges.

Ultimately, as pointed out by Charles Van Engen, ‘Christian knowledge about God is seen as cumulative, enhanced, deepened, broadened and expanded as the Gospel takes shape in each new culture.’[8] Humble partnership at the roundtable of Christ first leads us to this enhanced understanding of God, and then to a richer participation in his mission. Recently, I sat in my small multi-ethnic church in Croatia and marveled—a Roma pastor was preaching while Croats, Serbs, Americans, and Roma nodded along. In this part of the world, that is a remarkable witness to what is possible under the lordship of Jesus and the grace of the Spirit.

Endnotes

- Andrew Walls, The Cross-Cultural Process in Christian History (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2002).

- Two examples illustrate the complexity: in some contexts, groups self-identify as Gypsy while in others it is offensive; Sinti do not self-identify as Roma.

- See for example: Marcos Toyansk, ‘The Romani Diaspora: Evangelism, Networks and the Making of a Transnational Community’, Razprave in Gradivo: Revija za Narodnostna Vprasanja (2017) 79:185–205.

- Daniel Krása, Ňilaj, ‘The Banjara: A Nomadic Tribe of India and Possibly One of the Cousins of Europe’s Roma’, Romano džaniben (2007), 45-65; B. Shyamala Devi Rathore, ‘A Comparative Study of Some of the Aspects of the Socio-Economic Structure of Gypsy/Ghor Communities in Europe and in the Andhra Pradesh, India,’ European Journal of Intercultural Studies 6:3 (1996), 15-23; Donald Kenrick, Historical Dictionary of the Gypsies (Romanies) 2nd ed (Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, 2007).

- It is difficult to find reliable numbers of churches and Christians, just as in many contexts it is difficult to know accurate population numbers. However, a few estimates can offer some examples: an estimated 800 Roma churches in Bulgaria; Romania has numerous movements—one movement alone has 200 churches; an estimated 140,000 believers in France and 200,000 in Spain. Manuela Cantón-Delgado, ‘Gypsy Leadership, Cohesion and Social Memory in the Evangelical Church of Philadelphia’, Social Compass (2017), Gypsy and Traveller International Evangelical Fellowship 2014 Report, Rene Zanellato; Magdalena Slavkova, ‘Prestige and Identity Construction Amongst Pentecostal Gypsies in Bulgaria’ in D Thurfjell & A Marsh eds. Romani Pentecostalism: Gypsies and Charismatic Christianity (New York: Peter Lang International Academic Publishers, 2014): 57–74

- See, for example: Tatiana Podolinská and Hrustič, Tomaš, ‘Religion as a Path to Change? The Possibilities of Social Inclusion of the Roma in Slovakia’ (2010); Miroslav Atanasov, ‘Gypsy Pentecostals: The Growth of the Pentecostal Movement Among the Roma in Bulgaria and its Revitalization of Their Communities’, Asbury Theological Seminary (2008).

- Florencia Ferrari and Martin Fotta, ‘Brazilian Gypsiology: A View from Anthropology’, Romani Studies 24.2 (2014),11-136; 113.

- Charles Van Engen, ‘Five perspectives of Missional Theology’, in Appropriate Christianity, ed. Charles Kraft (2005), 183-202; 197.

Photo credits

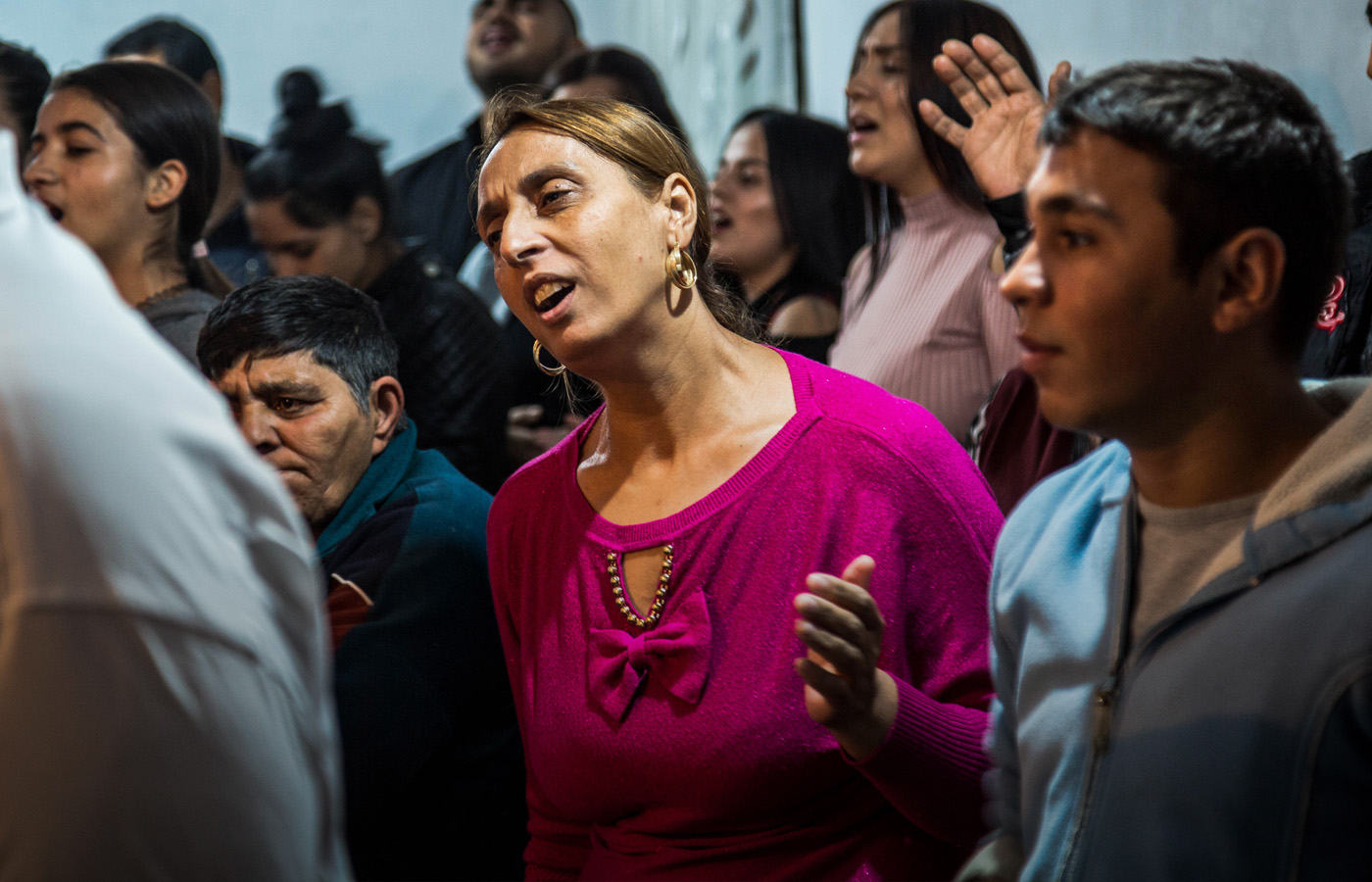

Feature image: “Roma Pentecostals in Southern Serbia” by Jason Autry for The Good Story, Co.

Photo image ‘Two Gypsies in Cluj-Napoca, Romania‘ by Gmihail (CC BY-SA 3.0 RS).