The Lausanne Covenant defines evangelization as ‘the whole Church [taking] the whole gospel to the whole world’ (Covenant, pt-6).[1] The first ‘whole’ of the popular three visions of mission is the inquiry into how the whole church can engage in mission. This brief article will identify the challenges in today’s mission in fulfilling this novel vision and propose areas to explore in resolving the challenges.

Challenges in the Current State of Mission

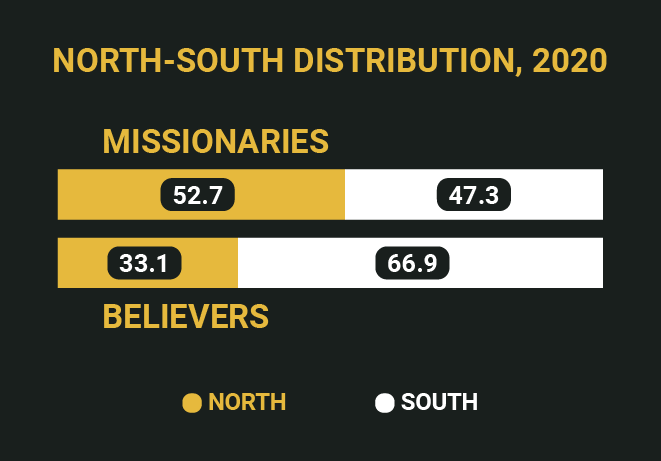

The biggest challenge is that only tiny fractions of today’s church are directly involved in mission. The third edition of the World Christian Encyclopedia (2020) reveals that it takes almost 6,000 Christians to send and support one missionary. If we zoom in on the picture, the challenge is even more serious: in the Global North (Europe and North America), it took slightly less than 4,000 believers to send one missionary, but it took more than 8,000 believers in the Global South (Africa, Asia, Latin America, and Oceania) to do the same.[2] The result is that the Global South sends less than half of the world’s missionaries, even though it has more than two-thirds of the world’s Christians.

The Global South sends less than half of the world’s missionaries, even though it has more than two-thirds of the world’s Christians.

Another picture to look at is the trajectory of the recent missionary movement. The number of missionaries grew from 62,000 in 1900 to 425,000 in 2020. But in 1900, with 522.4 million Christians, it took only 1,220 believers to send one missionary. By ratio, the church’s involvement in mission declined more than three times! It may explain why the Christian proportion of the world population deteriorated from 34.5 percent in 1900 to 32.3 percent in 2020.[3] How do we understand this serious inefficiency and its implications? There are at least three areas we can explore.

The first is the ‘elitist’ nature of the modern missionary movement, rooted in its history. The term ‘elitist’ does not describe an attitudinal aspect but the specialized and professionalized status of missionaries. Many trace the beginning of the modern missionary paradigm to the sixteenth-century Counter-Reformation movement of the Catholic Church. Facing the threat of the new Protestant movement and the discovery of new territories, such as the Americas, the Roman Catholic Church added orders of missionaries, including the Jesuits, to its existing structure. Thus, mission was relegated to a small group of professionals. This paradigm did not include the participation of local congregations or people in the pews. The Protestant mission since the eighteenth century continued this paradigm, although now churches (both denominations and local churches) have developed their own mission structures. Nonetheless, mission is still considered as what the church does ‘out there’ through specialists called ‘missionaries’.

The second is the misalignment of this historical paradigm with the original vision of mission mandated by Christ and practiced by the early church. Christ gave the mission mandate to all believers, ie the whole church. It is best expressed in his priestly prayer: ‘As you sent me into the world, I have sent them into the world’ (John 17:18). Luke links the outpouring of the Holy Spirit upon all the 120 gathered in the upper room to the Lord’s mission mandate: ‘But you will receive power when the Holy Spirit comes on you; and you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth’ (Acts 1:8).

The Book of Acts also records many instances where ordinary believers actively fulfilled the missionary call. The nameless believers, including non-Jews, escaped persecution in Jerusalem and spread the gospel as they moved (11:19–20). As they preached, ‘the Lord’s hand was with them,’ and ‘many turned to the Lord’ (11:21), not much different from the ministry of the apostles. Those scattered, ordinary believers ended up establishing the church in Antioch.

Scattered, ordinary believers ended up establishing the church in Antioch.

The church in Ephesus is another extraordinary work of evangelism. In two years of Paul’s daily preaching and teaching, all the Jews and Greeks who lived in the province of Asia heard the word of the Lord (19:10). It had to be ordinary believers who actively traveled to different parts of Asia and passionately shared the good news. With the assumption that most of them were new in the faith, mission is God’s call to the whole church and every believer. The current mission practice, therefore, does not faithfully reflect the Lord’s vision of mission.

The third is the practical challenge this historical mission paradigm poses to new churches in the Global South. Since the sixteenth century, the main players in Christian mission were Western churches. They were also politically powerful and colonized many nations. They were culturally ‘advanced’ and economically ‘developed’. The mission paradigm, developed by the churches in these Western powers, required substantial financial resources to prepare, send, and maintain their missionaries. If the growing churches in the Global South are now increasingly involved in the missionary movement, this resource-heavy mission paradigm can be an obstacle.

Questions in Closing the Gap

Perhaps the common element in the three challenges discussed above is a discrepancy that I am going to elaborate upon. This discrepancy encompasses challenges that range from the theological to the historical and practical. I will cast these challenges in three questions.

The first question is how to shape Christian mission according to the biblical vision. If we read the Scriptures closely, there are two mission paradigms. In Acts 19, the apostle Paul may represent the ‘elitist’ model as a recognized and trained specialist, while the ordinary believers in Acts may represent mission by ‘the rest of us’. What the church must restore is this democratic aspect of mission mobilization. This has to be a global process, with meaningful collaboration between the growing churches in the South and the traditional mission churches in the North.

Some long-held assumptions will be challenged. One is the assumption of what mission is. We have long heard, ‘If everything is mission, nothing is mission.’ If the church’s presence in the world, especially in a hostile situation, is already a missional act (per the Lord’s priestly prayer in John 17), everything about that church is on Christ’s mission. It is time for managerial mission or missiology to meet the Lord of mission.

Secondly, how can we discern the leading of the Holy Spirit in the formation of the missionary movement? One way is to discern the intentionality of mission. While we need to recover the organic aspect of mission, the church’s intentional effort to build a systematic structure for mission, both in the South and the North, should be strengthened. However, the Christendom model and paradigm should be scrutinized closely. The prerequisite of the historical model was ‘power’, and this model is a stark contrast to the kenotic model that follows Christ’s self-emptying of power by his incarnation. The latter will enable churches with fewer resources to embrace the mission call.

The prerequisite of the historical model was ‘power’, and this model is a stark contrast to the kenotic model that follows Christ’s self-emptying of power by his incarnation.

Lastly, what will open our eyes to see new and creative mission practices across the world, such as the Youth with a Mission movement, which radically broke new ground for mission? One possibility is for the global mission community to diligently gather stories of creative engagement with people of different faiths. One social anthropologist suspected that the Muslim converts through Filipino Christian domestic helpers in the Middle East would outnumber those who came to the Lord through ‘missionaries’. If this is true, then its implications are profound. The former serves while the latter teaches; the former comes with weakness while the latter comes with strength; the former witnesses by becoming part of the family (or incarnation) while the latter stays as a stranger.

Another example is what is called the Bhojpuri Breakthrough in northeast India.[4] This national mission movement has turned Bhojpuri, the heartland of Hinduism and the graveyard of missionaries, into a home for vibrant Christian communities. Within three decades, this state with a population of 100 million witnessed Christianity grow from 0.0001 percent (or 10,000 believers) to 12 percent (or 12 million believers), all by the national leadership, through local resources, wholistic approaches, and the manifestation of God’s supernatural work. It broke caste and denominational lines.[5] Such creative engagements abound, particularly in South-to-South mission settings. Many stories of and reflections on missionary movements in Latin America and Africa can be easily added. The whole church will be served well by learning from our brothers and sisters who experiment on God’s mission under the guidance and empowerment of the Holy Spirit.

We live in a time when a radical rethinking of mission is called for and feasible.

The whole church, with every believer, is called to God’s mission.[6] The historical development of Christian mission, especially in recent centuries, made the Christian faith a truly global religion. At the same time, a monumental task is before us to mobilize the whole church and every Christian for mission. And we live in a time when a radical rethinking of mission is called for and feasible. This will require the whole church to come together, both global and interdenominational, and both mission thinkers and practitioners.

Endnotes

- This article is based on the author’s presentation at the Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary during its Annual Mission Week, Sept 2021. The author wishes to express his heartfelt appreciation to Robert Antonucci, assistant director of the seminary’s Wilson Center for World Missions.

- Todd M. Johnson and Gina A. Zurlo, eds., World Christian Encyclopedia, 3rd ed. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020), 32–34.

- Gina A. Zurlo, Todd M. Johnson, and Peter F. Crossing, ‘World Christianity and Mission 2020: Ongoing Shift to the Global South,’ International Bulletin of Mission Research 44, no. 1 (January 2020): 8–19.

- Victor John and Dave Coles, Bhojpuri Breakthrough: A Movement That Keeps Multiplying (Monument, CO: WIGTake Resources, 2019).

- For the leader’s reflection, see Victor John and David Coles, ‘God’s Mighty Work in the Graveyard of Missions: Transformation Breaking Forth among the Bhojpuri People of North India,’ in Wonsuk Ma, Opoku Onyinah, and Rebekah Bled, eds., The Remaining Task of the Great Commission and the Spirit-Empowered Movement (Tulsa, OK: ORU Press, 2023), 221–36.

- Editor’s Note: See article entitled, ‘How Do We Measure Missional Understanding of Churches?’ by Jim Memory in Lausanne Global Analysis, January 2022, https://lausanne.org/content/lga/2022-01/how-do-we-measure-missional-understanding-of-churches.