At the outset I want to stress that I believe in scholarship, but with a purpose. I am reminded of my spiritual mentor Dr John Stott’s vision of ‘scholar saints’. I also believe in an ‘and . . . also’ rather than an ‘either . . . or’ way of looking at realities.

This analysis of theological education is based on my 44 years of involvement in ministry and theological training. My thinking has been sharpened by my involvement with 20 or more seminaries in various nations of Asia while serving with the Overseas Council[1] during the past twelve years. It has also been shaped by exposure to the challenges posed by the first-generation new believers who are now forming the ‘emerging churches’ in India and many other nations in Asia and the majority world.

First-generation believers lack deep discipleship under the lordship of Jesus Christ in their lives, which would transform their worldviews.

The state of theological education in the majority world

Most of the emerging churches are made up of first-generation believers. Therefore, they come with totally different sets of worldviews. They lack deep discipleship under the lordship of Jesus Christ in their lives, which would transform their worldviews. The teaching of God’s Word, therefore, is of paramount importance. However, they come from downtrodden communities; hence, their education is minimal and discipling them must be our priority. There is a significant leadership deficit in many regions where the church is rapidly growing.

This leadership deficit has been quantified by research conducted by the Center for the Study of Global Christianity, at the Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. Over two million Protestant pastors in the majority world lack formal, biblical training.[2] Ninety percent of churches worldwide have leaders with no formal training; and with the increasing rate of conversions, there is a global need of hundreds of new pastors every day.[3]

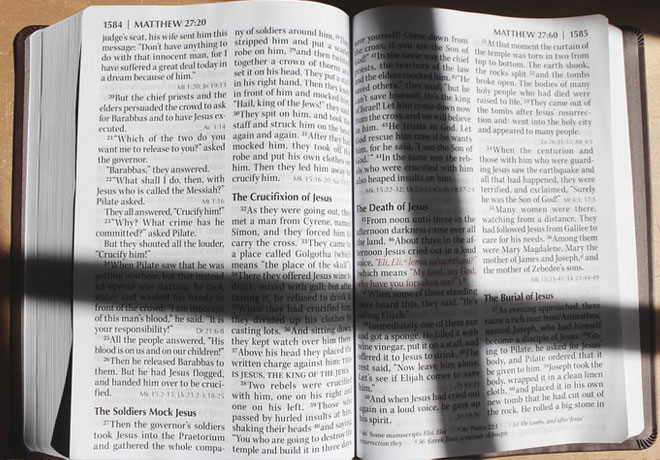

While formal theological education makes a critical contribution to the long-term health of the church, non-formal approaches address the large and growing numbers of those needing basic pastoral training, but for whom formal training is neither accessible nor appropriate. Most of the grassroots pastors or mission workers who can speak peoples’ heart language are also educationally deprived, but they are committed Christians. They need training, but much of it must be orally transmitted through non-formal learning methods. The materials from traditional theological education place a heavy emphasis on reading and writing, which is quite difficult for oral-based learners. They also carry different worldview presuppositions. Therefore, we need adaptable materials with a solid biblical base which are easily transferable according to the needs of people.

German theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768 – 1834)

Historical background of theological education

Theological education as it exists today in our theological colleges and seminaries is the product of the 18th-century Enlightenment. In many ways it follows the paradigm set by German theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768 – 1834). He wanted church ministry education to be recognized by the university. Acceptance by academia led to the compartmentalized silos of Old Testament, New Testament, Theology, History of Christianity, and Practical Theology, with a dimension of the study of religions. Schleiermacher’s philosophy was moulded by the academic heritage of Aristotelian logic and higher literary criticism of the Bible.

It is also the product of a ‘Christendom’ mentality and thus a majoritarian Christian worldview. This is not a biblical worldview that undergirds the reality for most Christians in the Global South, who live as religious minorities and need to address people of other faiths as the early church did.

The case study of Indian theological education starts in 1818 with the establishment of Serampore College, founded by William Carey, Joshua Marshman, and William Ward. It became a fully-fledged university by Charter of the Danish King (who sponsored the early missions in India) in 1827. Serampore was followed by prominent denominational theological colleges and divinity schools in various parts of India, including Bishop’s College (Kolkata), Leonard Theological College (Jabalpur), United Theological College (Bangalore), and the Orthodox Theological Seminary (Kottayam). Because of their liberal theological antecedents these colleges were the preferred avenues for the ministry training of the historical-traditional churches. As higher literary criticism became more prominent and as many nationals received their higher academic credentials from institutions in Germany and elsewhere in the West with a liberal persuasion, the colleges became the training grounds for ‘priests of the cult’, lacking missionary vision. Christianity was slowly being taken over by pluralism as its vanguard.

Serampore College

Against this backdrop, India witnessed the beginning of evangelical theological education. Most of the evangelical missions had smaller Bible schools for their training of national evangelists and pastors. It was at Yavatmal, Maharashtra, during the spiritual revival of 1953, that the evangelical mission bodies came together to form the Union Biblical Seminary (now in Pune, Maharashtra since 1983). The vision was formation for mission and ministry with academic excellence. The foundation was Christocentric, bibliocentric, missional, and ministry-oriented training. In the years to come, other Pentecostal and evangelical seminaries with similar vision took root in India. One can recognize similar patterns in other Asian nations. A key feature of these evangelical colleges and Bible schools was that they had missionaries as their faculty.

In the last 30 years in India there has been an explosion of church growth through Christian workers who have no connection with the traditional denominations and seminaries.

A new era of nationals within the evangelical seminaries being sent to the West to study for higher degrees opened in the 1970s. John Stott, as the Founder-Secretary of the Evangelical Fellowship within Anglican Communion (EFAC), invited prospective scholars to come and study in the UK under evangelical scholars or scholars sympathetic to the evangelical cause. By the end of 1980, EFAC became the Langham Scholarship which today is Langham International Partnership. This one servant of God, followed by many others committed to the cause of the evangelical scholarship, has left a legacy today of a great number of evangelical scholars in the majority world.

The evangelical institutions took seriously their heritage of training or theological education as formation for ministry and mission with academic excellence. This phenomenon saw the rise of respected evangelical leaders in India and many other nations during the 1980s and 1990s. However, after the mid-1990s and into the new millennium one begins to detect a shift.

The divide between the church and theological education has widened. In the last 30 years in India there has been an explosion of church growth, much of it, especially in North India, through Christian workers who have no connection with the traditional denominations and seminaries. As a result, these leaders are not being equipped by the seminaries, nor are the leaders of the seminaries well acquainted with the needs and challenges of the emerging churches.

The students’ vision in many cases has changed. It is a normal pattern to hear at the graduation exercises that nearly 60 percent of graduates are aspiring to ‘further studies’, rather than ministry. One also detects another pattern: students complete their first and secondary degrees in theology, serve in one of the Bible schools or seminaries for a year or two and then do a master’s degree with a view to being absorbed by one of the mushrooming seminaries.

The real danger we face in evangelical theological education today is that it is being overtaken by academia, without the vision for mission and ministry.

The challenges we face today

The real danger we face in evangelical theological education today is that it is being overtaken by academia, without the vision for mission and ministry.[4] In many countries such as Indonesia, South Korea, Philippines, and Thailand, governments have forced theological education to move into higher education or university frameworks. This has dragged it further into academia, with an over-emphasis on cerebral learning rather than professional training such as is found in subjects such as medicine, law, and engineering.

Faculty are pressed either by governments or by the demands of scholastic careers to ‘publish or perish’. There is a weakening of the understanding of theological education as formation for mission and ministry. Spiritual and character formation have become appendages. The requirement to publish and research is so overwhelming that discipling and mentoring of students are suffering.

As a result of this shift, the mission agencies and mega churches have started their own theological training programs, in order to keep their DNA alive. Some even say, ‘seminaries are cemeteries’. One mission leader told me that his problem is that he sends a good church planter for training, but after finishing their studies they just want to settle down in a church with no more zeal for church planting.

A much-needed paradigm shift

The time has come for us to recognize some key realities, if evangelical theological education is to be effective and not become a fossil:

- Theology is for the whole church. Paul and other New Testament writers wrote for the grounding and rooting of the church in God’s Word (Col. 2:6-7). It is not for the pursuit of the few to be elitist leaders within the church.

- Theology as ‘Theos-Logos’(the study of God) needs transformation to ‘Theos-Eulogeo’—the praise of God. Today theological education has become a cerebral pursuit. Some even define theology as Christian philosophy rather than a way of life.

- It is important to note that when Paul wrote to Timothy and Titus, his emphasis was on their character formation, undergirded by biblical theology.

- The present paradigm of student fees, donations (fund-raising in the West), and expenses is no longer viable for two reasons. Firstly, students who can make a difference in society tend to be bi-vocational, as they are disillusioned by church leadership and want to avoid three to four years of residential theological education. Secondly, the new millennial donors are more interested in outcome and impact-based learning than the existing traditional theological degrees.

- We need to re-envision theological education as ‘discipling the disciplers’. There is an urgent need to focus intentionally upon transformative theological education, with the focus on outcomes that are rooted in missional and ministerial formation.

- Theological education needs to focus on the emerging churches where many new believers come from marginalized and oppressive backgrounds. The pastors who minister to them have minimal formal school education. However, they speak the heart language of people and are able to present the gospel effectively to plant churches. What about their training? They need theological education in their vernacular, with oral communication as the key, while the growing mass of people at the grassroots need their learning patterns to be taken seriously.

- I struggle with a question similar to that faced the early church: do Gentiles first have to become Jews in order to learn about and follow Jesus Christ? Do pastors, evangelists, and those interested in learning God’s Word first have to be English speaking, possessed of an analytical mind, and versed in Aristotelian logic? The early church lived as a minority among the people of other faiths. They suffered trials and persecution and yet communicated the wisdom of God in both written and oral forms. Most of the believers were from marginalized and despised backgrounds but they responded to the Good News. Is this not the reality of the present-day world and specially the majority world? Can we help people develop theological education that flourishes and takes shape in earthen vessels of different soils so that the living waters of the Lord may quench the thirst of many who are dying without Christ?[5]

So which direction will theological education take? We need a two-pronged approach, which comprises both formal and non-formal theological education, with the main focus on the majority world’s contextually nuanced styles of learning. It is important not to be elitist and traditionalist, failing to recognize the need for transformation that will lead the church of our Lord Jesus Christ to be rooted and grounded in his Word.

Endnotes

- https://uwm.org/overseas/

- Editor’s Note: See article by Kirsteen Kim entitled, ‘Unlocking Theological Resource Sharing between North and South’, in November 2017 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis https://lausanne.org/content/lga/2017-11/unlocking-theological-resource-sharing-north-south.

- https://gordonconwell.edu/center-for-global-christianity/research/quick-facts/.

- Editor’s Note: See article by Brian Woolnough entitled, ‘Reforming the Preparation for Ministry and Mission’, in this issue of Lausanne Global Analysis https://lausanne.org/content/lga/2019-09/rethinking-seminary-education.

- Editor’s Note: See article by Ramesh Richard entitled, ‘Training of Pastors’, in September 2015 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis https://lausanne.org/content/lga/2015-09/training-of-pastors.

Photo credits

Feature cropped image from ‘Serampore College, Hooghly, West Benal.‘ by gangulybiswarup (CC BY-3.0).