Shame disrupts God’s design for the world. The mission of God involves removing shame and restoring honor. Honor and shame are inherent to the gospel and essential for Christian mission.

In the Beginning: Our family history

God created humans with glory and honor (Ps 8:6). Adam and Eve were honored co-regents, naked yet unashamed (Gen 2:25). Then shame entered the story.

After Adam and Eve disobeyed God, they hid and covered themselves—the hallmarks of shame. The human family ‘lost face’ before God and was banished from his presence. To remove this disgrace, people manipulate cultural systems to ‘make a name for themselves’ (Gen 11:4).

Shame is not limited to non-Western contexts.

Shame is not limited to non-Western contexts. People of every culture feel unworthy and fear rejection before others, because we all ‘fall short of the glory of God’ (Rom 3:23).

Exposing Western shame

Western thought has long associated shame with ‘pre-civilized’ cultures. However, conversations in the media are exposing the prominence of shame within Western cultures:

- Brene Brown’s top-rated TED talks about shame have over 30 million views.

- Andy Crouch’s article ‘The Return of Shame’ in Christianity Today (March 2015) claims, ‘large parts of our culture are starting to look something like a postmodern fame-shame culture’.[1]

- No less than four separate Christian books released in 2016 carry the title Unashamed.[2]

- The issue of ‘internet shaming’ is widely discussed in New York Times articles, TED talks, and best-selling books.[3]

Western culture is becoming more shame-oriented.

Western culture is becoming more shame-oriented. However, Western Christianity emphasizes legal aspects of salvation such as forgiveness of sins and innocence. Mission in Western contexts must offer biblical solutions to people who say, ‘Even if I am innocent, I cannot lift my head, for I am full of shame’ (Job 10:15).

The global face of honor-shame cultures

Honor and shame are prominent in Majority World cultures, where these moral values form the ‘operating system’ of everyday life. People avoid disgrace and seek status in the eyes of the community. Four global realities necessitate a larger role for honor and shame in twenty-first century theology and mission:

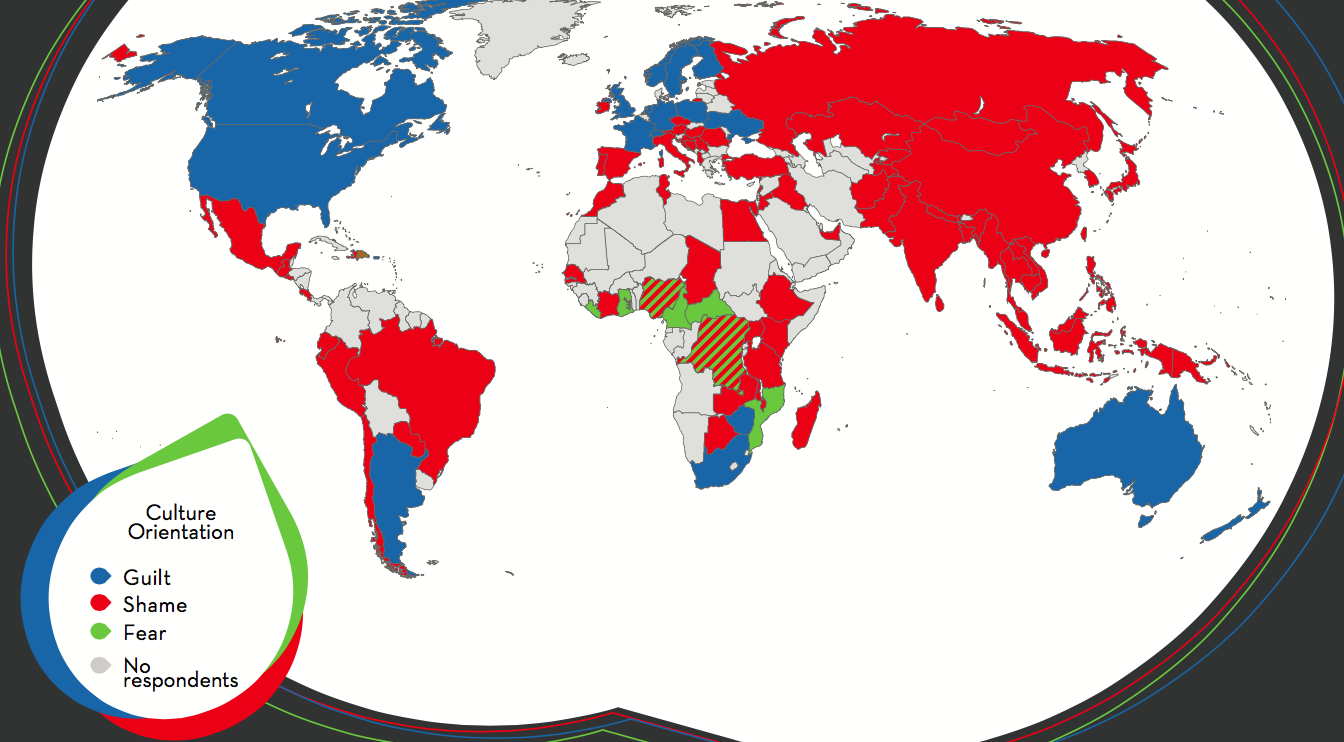

- Global Culture Types. Honor-shame is the dominant culture type for most people in the world, as indicated in the map below from Global Mapping International.[4] Culture shapes people’s experience of sin (eg guilt, shame) and notion of salvation (eg forgiveness, honor); therefore, Christian mission must account for this global predominance of honor-shame cultures.

- Global Migration. Americans and Europeans now encounter people from honor-shame cultures. The surge of international students, refugees, and immigrants has changed the face of Western populations.[5] Understanding honor and shame helps Christians obey the Great Commandment of loving their neighbors from around the globe.

- Global Christianity. An increasing number of Christians come from honor-shame cultures. This shift in global Christianity mandates ongoing contextualization. The global church needs to articulate a theology that equips Majority World Christians to follow Jesus in their own sociocultural context marked by honor-shame realities.

- Unreached People Groups. Honor and shame pervade the cultural outlook of most people groups with limited or no access to the gospel. A biblical missiology for honor-shame contexts is strategic for fulfilling the Great Commission among all nations, especially those within the ‘10/40 window’.

This global prominence of honor and shame requires fresh missiological reflection. Timothy Tennent notes, ‘A more biblical understanding of human identity outside of Christ that is framed by guilt, fear, and shame will, in turn, stimulate a more profound and comprehensive appreciation for the work of Christ on the cross.’[6]

The solution of God’s honor[7]

God desires to bless the nations with honor and share his name with his people.

God desires to bless the nations with honor and share his name with his people. The restoration of status, which all people long for, plays a key role in God’s mission throughout history.

God called Abraham to a life of honor—a large family, a great name, blessings, and divine protection from dishonor (Gen 12:1-3). These covenantal promises extend to Israel. A nation of despised slaves became God’s treasured possession set ‘in praise, fame, and honor high above all the nations’ (Deut 26:19). God’s people are chosen to mediate God’s honor to all nations.

God’s Son left the glory of heaven to bring God’s saving honor to all people. Jesus testified to God’s true honor by breaking bread with outsiders, healing outcasts, and shaming shamers. On the cross—a symbol of grand ignominy—he bore our shame and restored honor. Now, ‘anyone who believes in [Jesus] will never be put to shame’ (Rom 10:11) because Jesus shares his glory with his people (John 17:22; Rom 8:14–18; Heb 2:10).

Honor and shame in contemporary mission: Practical suggestions

Jesus Christ dismantles shame and procures honor for the human family. The church now continues the mission of God to bless all nations with God’s honor.

Man is ashamed of the loss of his unity with God and with other men.13

Honor and shame is a socio-theological reality that affects all facets of biblical mission. God’s people must discern how to embody and proclaim God’s saving honor in particular contexts. Paul, Peter, and John faced this same challenge as they shepherded the early church. Their writings (especially Romans, 1 Peter, and Revelation) offer biblical examples of mission in honor-shame contexts.

Here are initial suggestions for incorporating honor and shame into seven areas of contemporary mission:

- Evangelism. Western gospel presentations emphasizing forgiveness of guilt have little impact on people affected by shame. The gospel announces that all people stand ashamed before God, but Jesus Christ offers an honorable status via adoption into God’s family. People must abandon their pursuit of worldly honors and get their ‘face’ from God. Biblical faith means honoring Jesus with undivided loyalty.

- Discipleship. Honor and shame are not merely cultural pressures but notions of value and worth that shape a person’s worldview. Thus, honor and shame are essential for discipleship.[8] Following Jesus means adopting God’s honor code for all areas of life, learning to value what God deems valuable. God’s imputed honor empowers Christians to resist cultural disgrace and live for the glory of God’s name, even in the face of shaming persecution (Acts 5:41; 1 Pet 4:13–15).

- Peacemaking. In honor-shame contexts, restoring honor is a prerequisite for reconciliation. People break relationship when they feel disrespected; restoring face promotes peace. Western approaches of punitive justice exacerbate shame by making an example of the perpetrator. Yet, the practice of ‘restorative justice’ emphasizes reintegration back into community and so might be a more effective approach to reconciliation in shame-sensitive contexts.[9]

- Development and Aid. Poverty involves social isolation and shame as much as hunger. Free handouts intensify humiliation. Emerging mission paradigms more honorably address poverty. Business as mission (BAM) provides jobs with dignity.[10] Asset-based community development (ABCD) affirms people’s innate honor by starting with their own assets. Effective development increases people’s social capital.

- Partnerships. Westerners approach ministry partnerships in a manner akin to business contracts (eg MOUs, defined objectives, signed agreements). In honor-shame contexts, this approach confuses and offends others, implying minimal relationship. Financial relationships must account for the dynamics of patronage—the wealthy have a moral obligation to share benevolently, and clients reciprocate with non-material resources such as honor and loyalty. Patronage can be responsibly leveraged for kingdom purposes.[11]

- Prison Ministry. Psychiatrist James Gilligan, MD, notes, ‘I have yet to see a serious act of violence that was not provoked by the experience of feeling shame and humiliated, disrespected and ridiculed, and that did not represent the attempt to prevent or undo this “loss of face”.’[12] Guilty criminals live as shameful outcasts before and after the crime. Prison ministry should account for shame in the cycle of violence.

- Church-planting. Most people come to Jesus through a believing relative or the Christian community. In honor-shame cultures, relationships (more than facts) guide life decisions. Following Jesus means transferring one’s allegiance and relational obligations to God’s community. People tangibly experience God’s honor in the church.

Honor and shame should positively inform other aspects of Christian mission (eg counseling, ethics, theological education, pastoral training, and medical care) and its audiences (eg college students, refugees, gang members, LBGTQ, Muslims).

Conclusion

The mission of God involves restoring honor to the shamed. The theological realities of honor and shame are essential to the gospel and Christian mission.

Endnotes

- Andy Crouch, ‘The Return of Shame’, Christianity Today, March 2015.

- Christine Caine, Unashamed: Drop the Baggage, Pick up Your Freedom, Fulfill Your Destiny (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2016); Tracy Levinson, Unashamed: Candid Conversations About Dating, Love, Nakedness and Faith (TBL Publishing, 2016); Lecrae Moore, Unashamed (B&H Books, 2016); Heather Davis Nelson, Unashamed: Healing Our Brokenness and Finding Freedom from Shame (Wheaton: Crossway, 2016).

- Jon Ronson, ‘How One Stupid Tweet Blew Up Justine Sacco’s Life’, The New York Times, February 12, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/15/magazine/how-one-stupid-tweet-ruined-justine-saccos-life.html; Jennifer Jacquet, Is Shame Necessary?: New Uses for an Old Tool (New York: Pantheon, 2015); ‘The Outrage Machine’, The New York Times, June 19, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/video/us/100000004467822/the-outrage-machine.html; Monica Lewinsky, The Price of Shame, accessed June 22, 2016, http://www.ted.com/talks/monica_lewinsky_the_price_of_shame; ‘Shame on You(Tube)’, CBC News, accessed June 22, 2016, http://www.cbc.ca/radio/ideas/shame-on-you-tube-1.3086407.

- ‘Culture’s Color, God’s Light’, Global Mapping International, 2016, http://www.gmi.org/services/missiographics/library/honor-shame/. The data is based on the initial 8,500 results from http://theculturetest.com.

- Editor’s Note: See article by Sadiri Joy Tira entitled ‘Diasporas from Cape Town 2010 to Manila 2015 and Beyond’ in the March 2015 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis.

- Timothy Tennent, ‘Anthropology: Human Identity in Shame-Based Cultures of the Far East’, in Theology in the Context of World Christianity: How the Global Church Is Influencing the Way We Think about and Discuss Theology (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2007), 92.

- For a fuller discussion of honor and shame in salvation-history and Christian theology, see Jayson Georges and Mark D. Baker, Ministering in Honor-Shame Cultures: Biblical Foundations and Practical Essentials (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2016), 67–116.

- Jackson Wu, ‘Does the “Plan of Salvation” Make Disciples? Why Honor and Shame Are Essential for Christian Ministry’, Asian Missions Advance (January 2016), 11–17.

- Howard Zehr, The Little Book of Restorative Justice (Intercourse, PA: Good Books, 2015).

- Mats Tunehag, ‘Business as Mission’, Lausanne Global Analysis 2:5 (Nov 2013).

- Editor’s Note: See article by Phill Butler entitled ‘Is Our Collaboration for the Kingdom Effective?’ in the January 2017 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis.

- James Gilligan, Violence: Reflections on a National Epidemic (New York: Vintage, 1997), 110.

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Ethics (New York: Touchstone, 1995), 20.