Editor’s Note: This piece was originally published on JohnStott100.org, a campaign website commemorating the centenary of John Stott’s birth. It is republished here with permission.

The two leaders with whom the Lausanne Movement is most closely associated are Billy Graham and John Stott. Billy was the face and voice of the movement. That voice echoed through the halls of the Palais de Beaulieu in Lausanne, Switzerland, in 1974 on the first night of the First Congress on World Evangelization exclaiming, ‘Let the earth hear his voice!’

John Stott, however, was the head and heart of Lausanne.

I first met Uncle John 25 years ago while I was a student at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School where I had the unexpected blessing of lunch with him. It was like meeting a real-life hero. Not the kind that you watch in movies, but the kind that we all truly need. Not a man of fame and fortune, but a godly, wise, and humble servant.

The topic of our conversation was birds—a topic Uncle John was always animated about. After sharing with me some of the fascinating lessons on life and faith to be learned from birds, he expressed his hope to one day write a book on his favorite hobby. A few years later he did indeed share his personal and biblical insights on ‘orni-theology’ in The Birds, Our Teachers. Only years later did word get around that the secret to getting John Stott to accept a speaking invitation was to entice him with an opportunity to see a rare bird!

In the Lausanne Movement we often talk about giving focus to works of ‘enduring value’, which includes many of the books that Uncle John wrote. But perhaps one of his greatest contributions to the global church was his serving as the chief architect of The Lausanne Covenant. The Covenant, in the words of Stott’s protege Chris Wright, was ‘prophetic in the sense of speaking in a way which applied the Word of God to the realities of the hour. And it retains its relevance and challenge now and indeed for generations to come.’

The Lausanne Covenant is widely regarded as one of the most significant documents in modern church history and has served as a faithful and inspiring theological grounding in the biblical faith that compels Christians to work together to make Jesus Christ known throughout the world. God’s head and heart are on display through Stott’s head and heart in The Lausanne Covenant.

Someone once said of John Stott that he had two noteworthy traits—he was ‘insightfully world-engaging and decisively Christ-focused’. And his heart and mind were no more warmly expressed than toward young people. In addition to his love for university mission, Uncle John also invested himself in global younger leaders. My surprise at being invited to lunch as a seminary student was based on my assumption that someone of his stature would prefer a quieter, nicer lunch with better company.

Years later, after I was called to lead the Lausanne Movement, I thought back to that lunch. I marveled at the gift that it was to have spent time with Uncle John at a time when only God knew the significance. Years later I was also able to have time with Billy a few years before he passed.

For Lausanne’s younger leaders, including alumni from Singapore 1987 (where Uncle John spoke and invested time with young emerging leaders like Ajith Fernando, John Piper, Doug Birdsall, and Susan Perlman), Port Dixon 2006 (my cohort with friends like Jason Mandryk, Allen Yeh, and Yaw Perbi), and Jakarta 2016 (with our current cohort of younger leaders like Sarah Breuel, Emmanuel Kwizera, and Manivanh Khy), we look at the black and white pictures from Lausanne I of Billy Graham and John Stott with a sense of awe.

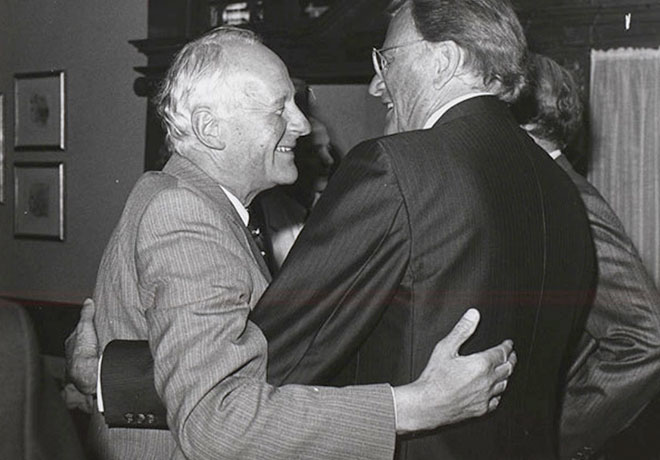

But looking a bit closer at history, it’s remarkable that both men were quite young at the time, considering the significance of their roles and the global nature of their ministries. Uncle John was 53 years old and Billy was 55. These were not two old leaders. These were leaders in their prime. And they demonstrated to global younger leaders over the years what friendship can look like. Not being the same but holding a united belief. Not having the same wiring but being committed to each another with tremendous respect for how God has gifted the other differently. Not always agreeing but learning deeply from the other.

Both leaders of integrity. Both incredibly godly and faithful servants.

John Stott, who served as the first chair of the Lausanne Theology Working Group, would be so pleased to know that today Dr Ivor Poobalan of Sri Lanka and Dr Victor Nakah of Zimbabwe serve as co-chairs.

In his last sermon (Keswick, 2007) Uncle John said,

I remember very vividly, some years ago, that the question which perplexed me as a younger Christian (and some of my friends as well) was this: what is God’s purpose for his people? Granted that we have been converted, granted that we have been saved and received new life in Jesus Christ, what comes next? Of course, we knew the famous statement of the Westminster Shorter Catechism: that man’s chief end is to glorify God and to enjoy him forever: we knew that, and we believed it. We also toyed with some briefer statements, like one of only five words—love God, love your neighbour. But somehow neither of these, nor some others that we could mention, seemed wholly satisfactory. So I want to share with you where my mind has come to rest as I approach the end of my pilgrimage on earth and it is—God wants his people to become like Christ. Christlikeness is the will of God for the people of God.

John Stott loved and commended to the global church the mission of bringing Christ to the world. And he loved and commended to global Christians the purpose of growing in Christlikeness.

I once had a car ride with a very close friend of Uncle John’s. I peppered him with questions about Stott’s habits, friendships, and impressions. His final statement left me speechless and with goosebumps up and down my arms: ‘He was the most Christlike man I ever knew.’

Many a person aspires to publish a lot of books, to be known worldwide, to have position and authority, and much more. Many a person thinks about what accolades and accomplishments they might one day have written on their tombstones or obituaries. But I can’t think of a single statement more aspiration-worthy and life-worthy than what was said of Uncle John Stott:

‘He was the most Christlike man I ever knew.’