In the 1880s, Australian sugar plantations recruited bands of young men from the Solomon Islands to work in their cane fields. The labor was hard and conditions harsh, and most of the men returned home when their two-year contracts ended. But in the meantime, and largely through the efforts of Florence Young and the Queensland Kanaka Mission that she organized on her family’s sugar plantation, the islanders were introduced to the gospel.

Samson Maeniuta was one of those young men. He committed his life to Christ and, when he returned to the Solomon Islands, took the gospel home with him. In 1892, he established a Bible school to encourage his fellow islanders to follow Jesus. The effort meant estrangement from his family, who preferred to continue with their traditional religion of ancestor worship, but Maeniuta persevered. The disciple-making movement that he and other sugar cane workers transplanted from Queensland is known today as the South Seas Evangelical Church. One in five inhabitants of the Solomons is a member.

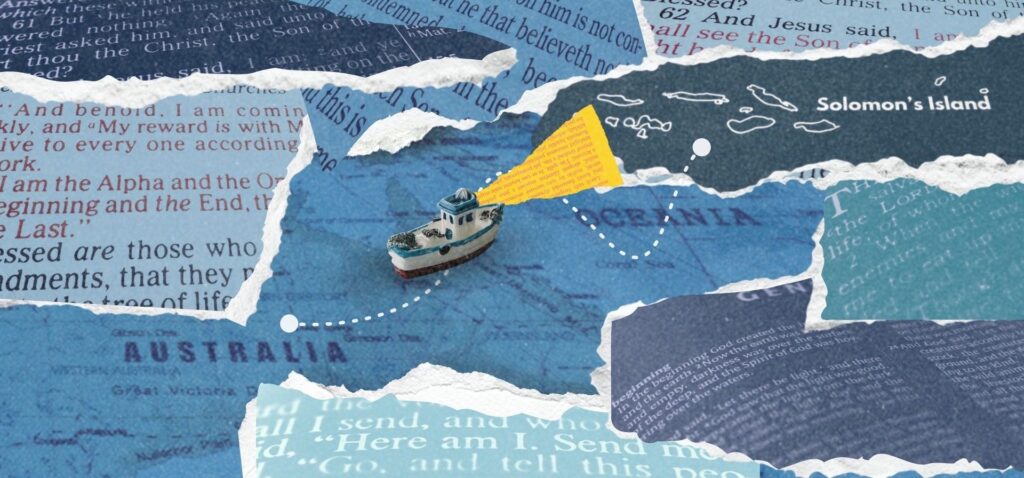

This history of God using economic opportunity, workforce migration, and faithful witness to extend his kingdom unfolded in Oceania. The smallest of earth’s six inhabited continents by population, Oceania is made up of Australia, New Zealand, and 5,100 islands in the Pacific Ocean.

Christians from Oceania met together at the Fourth Lausanne Congress held in South Korea in September 2024 to explore ways of extending gospel ministry in their region. A central focus of the discussion was ‘Great Commission gaps’. These are places, people groups and social spaces where the gospel has not yet entered.

Leaders asked themselves the question, ‘What are the greatest obstacles we face in order to fulfill Jesus’ command to make disciples?’ They identified major impediments such as generational differences, a crisis of discipleship in existing churches, complacency, disunity, and unwillingness to cooperate.

These hurdles may exist in other continents where Jesus followers are wrestling with the call to carry the gospel to the unreached. But when it comes to filling Great Commission gaps in Oceania, a huge hurdle that must be overcome is geography. That is because, as its name implies, Oceania is mostly, well, ocean.

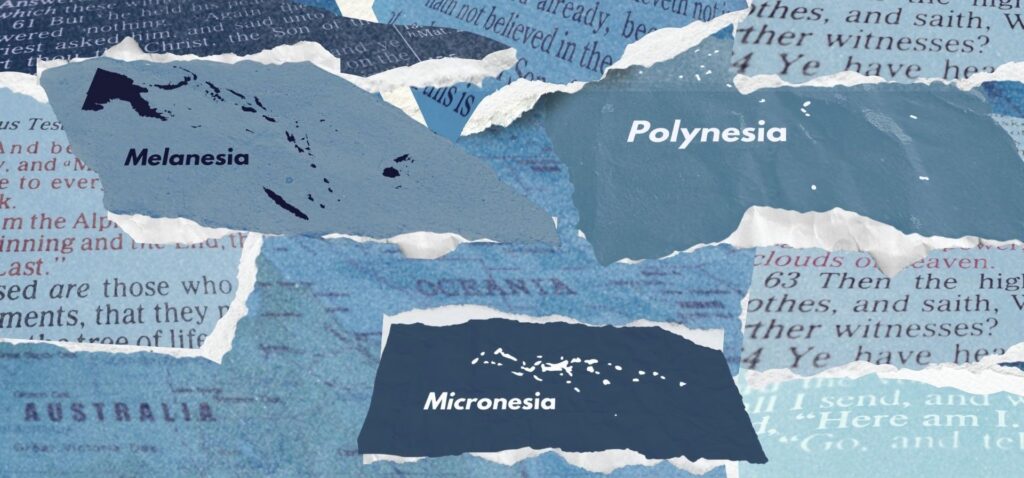

Apart from the Australasian continent, Oceania is comprised of the island groups of Micronesia, Melanesia and Polynesia. The three regions occupy an area of the Pacific larger than the continent of South America, but their combined populations could easily fit into the city of Buenos Aires.

Despite the vast stretches of ocean that separate them and centuries of little or no direct contact, Pacific islanders share many common cultural traits. Nowhere is this phenomenon more evident than on Rapa Nui, the eastern limit of Polynesia.

Also known as Easter Island, the 63-square-mile archipelago has become a world-renown tourist destination because of the hundreds of massive stone sculptures called Moai that are found there. Rapa Nui is so far from everywhere else on the map that it was the last place on earth to be inhabited by human beings. That took place around AD 1200, according to archeologists. And although the island has been part of Chile for over a century, the Rapa Nui people feel closer to the Maori who live 4,400 miles away in New Zealand, and their Hawaiian cousins 4,600 miles to the north.

Rapa Nui is so far from everywhere else on the map that it was the last place on earth to be inhabited by human beings. That took place around AD 1200

‘Those kinship ties must be taken into account when it comes to undertaking collaborations to fill Great Commission gaps,’ says Alejandro Torres, veteran pastor of a multi-ethnic evangelical congregation on Rapa Nui.

‘People of Rapa Nui ethnicity receive the Word of God more readily when Christians come from Polynesia, such as Hawaii, New Zealand, or Tahiti,’ he said. ‘They feel little (cultural) affinity with us Chileans.’1

This does not necessarily mean that the door to collaboration with Rapa Nui Christians is closed to outsiders. However, Torres stresses that visitors should plan extended stays in order to build relationships with the approximately 120 native islanders who have become followers of Jesus.

An important step to making disciples among the Rapa Nui has been the translation of the New Testament into their language. Wycliffe translators Robert and Nancy Weber labored for 40 years on the island to learn the language and translate the Scriptures. As with most Bible translation projects, the Webers developed close relationships with their language assistants, who eventually accepted Christ and helped plant the Rapa Nui church.

Bible translation has historically been one of the most successful collaborative efforts in Oceania, according to Julian Dunham, Oceania Co-Regional Director for the Lausanne Movement: ‘This has been led by the Bible Society, but to their credit they haven’t controlled or monopolized the collaboration,’ he said. ‘All parties have felt empowered and willing to contribute.’2

The Lausanne Congress seems to have awakened interest in disciple-making as well. Edgar Pollard, a great-grandson of Samson Maeniuta, has a vision to mobilize Solomon Islanders to make disciples, both at home and abroad.

Edgar Pollard, a great-grandson of Samson Maeniuta, has a vision to mobilize Solomon Islanders to make disciples, both at home and abroad.

‘As islanders we have been blessed by this beautiful gospel for 100 years or so. Now there needs to be a greater emphasis on being part of the mission to reach those unreached people,’ he said. ‘Sometimes we feel like we are at the ends of the earth, isolated and disconnected and not aware of the spread of the gospel in the rest of the world. We are, in a way, not up to date with the latest tools and ways of disciple-making. The global church has explored a lot of tools and content that could greatly benefit the islands.’3

Dunham sees technology in the digital age as providing tools to fill Great Commission gaps like these. ‘Oceanians are early adopters of technology, so not only will we utilize technology in collaborations, but we will also be key collaborators in digital innovation for mission. Collaborations already emerging are in areas that easily cross culture divides, like workplace and sports ministries,’ he added.

In discussions with one another at the Lausanne Congress, participants repeatedly acknowledged that, more than any other initiative, serious prayer and repentance are the first steps to fill Great Commission gaps in Oceania.

‘Revival is always preceded by leaders and believers everywhere humbling themselves, repenting of sin and seeking God in prayer’, they concluded in a joint statement. ‘We will engage with prayer movements that are already underway and promote new ones, especially in churches and the marketplace. We will boldly call churches to unite in prayer for revival.’

As Jesus followers in Oceania fulfill their pledge to pray, seek God, and collaborate with one another to fill Great Commission gaps, it is not difficult to imagine many more stories unfolding, like the saga of Queensland sugar cane workers turned Solomon Island church planters.

Photo

Image from biblesociety.org.au

Endnotes

- Cited from personal messages to the author.

- Cited from personal messages to the author.

- From personal interview with the author at the Fourth Lausanne Congress, September 2024.