Unpacking 50 Years: The Legacy of the Lausanne Movement with Doug Birdsall and Ramez Atallah

In this episode, we interview Doug Birdsall (former CEO of the Lausanne Movement) and Ramez Atallah (former Vice-Chairman of the Lausanne Movement). They share personal encounters with iconic figures such as Billy Graham, Thomas Zimmerman, and John Stott, while also unpacking the rich legacy of the Lausanne Movement. Together, they delve into the challenges faced by global missions today, share stories of unity among mission organizations, offer words of encouragement for younger leaders, and discuss their hopes for the landmark Lausanne Congress in Seoul 2024.

Show Podcast Transcript

Podcast Transcript

This transcript has been edited for readability.

- Introduction

- Doug Interview

- What sets Lausanne apart and what has given it such a lasting resonance

- The Legacy of Lausanne

- Lessons from Billy Graham & John Stott

- Billy Graham The Spirit of Lausanne

- The Influence of John Stott

- Reflections on the Third Lausanne Congress in Cape Town, 2010

- Looking Ahead: Seoul 2024 and Beyond

- Why Lausanne?

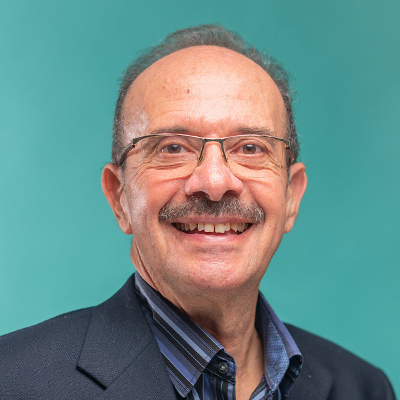

- Interview: Ramez Atallah

- How did you become involved in the Lausanne Movement?

- Inspirational Moments

- Most impactful moment in his life

- Other impactful moments?

- Advice to young leaders?

- 2010 Congress

- Misisons organizations unite

- Looking forward – missions in the future

- Prayer

- Clip from Chris Wright

If you would like to help us improve our podcast, please send us the feedback –

https://forms.gle/QbNzK7BGqqnFHPHc7

Introduction

Doug B

Lindsay Brown and I were with John Stott where he spent the last two or three years of his life, the College of St. Barnabas, an Anglican Retirement Community outside of London. Two things were interesting about that. While we were there, I asked him, I said, ‘Are you happy here?’ Because he spent all of his life in Central London. And there again, as Lindsay and I were both in our mid-fifties, and here’s John Stott in his eighties towards the end of his life, and he said, ‘I wouldn’t say that I’m happy here, but I am learning to be content.’ Now, all of us will eventually get old. And I thought, what a wonderful lesson to tuck into my mind and my heart, but to be content: godliness with contentment. It was great gain. And I saw that in John Stott, not in a book, not in a conference platform, but in a bed, in a retirement home.

Jason W

Welcome to the Lausanne Movement Podcast, where we have a passion to accelerate global mission together. I am your host, Jason Watson. And today’s episode. We sit down with Doug Birdsall and Remez Atallah to unpack the extraordinary legacy and impact of the Lausanne Movement. First up, we have Doug Birdsall who played a pivotal role in the global revitalization of the Lausanne Movement.

Doug served as executive chair of the Lausanne Movement from 2004 to 2013. And, under his leadership, the movement experienced profound renewal, culminating in the Third Lausanne Congress on World Evangelization in Cape Town in 2010.

Doug is a graduate of Wheaton College, Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, Harvard University, and the Oxford Centre for Mission Studies. Doug’s dedication to evangelization and global mission is truly inspiring.

In today’s interview, we will hear about personal encounters with our iconic figures like Billy Graham and John Stott and he unpacks the rich legacy of the Lausanne Movement.

And now for today’s interview

Doug Interview

Jason W

Doug, welcome to the podcast.

Doug B

Thank you, Jason. It’s really great to be with you.

Jason W

It’s truly a pleasure to have you with us today. In today’s interview, we are just going to be unpacking the incredible legacy of the Lausanne Movement that has had a 50-year history. Now, there’ll be some people listening to this podcast who’ll be familiar with Lausanne and its history, and there’ll be some who are not.

In your view, what sets Lausanne apart and what has given it such a lasting resonance the global Christianity?

What sets Lausanne apart and what has given it such a lasting resonance

Doug B

Thank you, Jason. That’s a great question, and it’s a story that I love to tell. I must say that though it involves some great people, it really is a God story. For one thing, it was a unique moment in history. We know the church was rapidly expanding, moving from a Eurocentric world to a truly globalized church. It was at a time in history when the world was really experiencing globalization. Travel and technology made it possible for people to come together, but it really was great people that were anointed of God who had been used by him for many years. And, namely, Billy Graham was the person who was the convener.

He had the vision. He was a man of global stature and enormous gifts and Christ-like character. He was very good friends with a man named Bishop Jack Dane. Who was a very skilled organizer. And then his younger brother-in-law, Leighton Ford served in a key role as the program chair. And then John Stott played an enormous role.

God used people like those that I’ve just mentioned along with several others. So, it was the time, it was the people, and it was also the great issues that were addressed there. Perhaps the greatest document in the church since the Reformation is the Lausanne Covenant and I think there’s no greater document in the modern era of missions than the Lausanne Covenant. There’s maybe one possible exception and that would be William Carey’s ‘Use of Means’ is referred to, written in 1792, but the Lausanne Covenant really articulated the convictions, the sheer beliefs and values of evangelicals around the world in non-sectarian language. And very quickly people began to identify with one another from across geographical, theological, and organizational lines and are just saying, are you a Lausanne-r? Do you embrace the Lausanne covenant? So, it really did create a global community.

There are just two other things that I will mention in addition to the Lausanne Covenant. First thing, everyone in the world today who’s an evangelical and has any interest in missions, knows about unreached people groups. That revolutionized the way the church thinks about mission and it energized the church. In1973, the year before, it was at the world Council of Churches commission on Mission and Evangelism basically indicated there was no longer use for missionaries. There was use for fraternal workers. There was use for cooperation in the work of the church around the world, but there was a sense that they saw now that the church is established. Every country on the face of the earth. We don’t really need missionaries. Well, the next year at Lausanne Ralph Winter, said the church and every nation on the earth . . . not even close. Not even close. There are 17,000 nations, he said, that have no access to the gospel. Well, I won’t unpack a lot of that, but it was so revolutionary. It took a couple of years for people to really understand what he was talking about, but now, mission organizations and local churches around the world have really been focused on taking the gospel where it is not and where it needs to be. That’s really a contribution of Lausanne 74 Congress and Ralph Winter referred to the 20 minutes that he spoke at Lausanne on a Saturday when not everyone was in the hall. That was the most significant 20 minutes of his life.

And then the third thing in addition to the Covenant and unreached people groups was what is known as article five of the Lausanne Covenant, Evangelism and Social Responsibility. And evangelicals had abandoned their commitment, their historic commitment to both the proclamation and the incarnation of the gospel because there again was perceived that the liberals were all about social justice and had forgotten about the centrality of the cross and redemption and salvation. Well, ‘74 really brought a correction to that, and it was primarily people like Samuel Escobar, René Padilla, Orlando Costas, primarily leaders from the Latin American world who were trying to make the gospel relevant to a continent that was on fire with Marxist ideology. So those were enormous contributions.

Billy Graham did not envision anything more than a 10-day event. He did not envision that there would be a second congress, or a third congress, or that there would be another congress 50 years later. There was a reluctance to start a movement, but God has blessed this Movement in wonderful ways.

Jason W

Wow, that is a powerful legacy and with such a legacy comes stories of tangible change. Doug, do you have any specific stories that come to your mind from your time in the Movement that you feel demonstrate the legacy of Lausanne?

The Legacy of Lausanne

Doug B

Well, I immediately think of my first engagement with Lausanne directly. Interestingly, I was a senior in college at Wheaton in the fall of 1974. I actually met Leighton Ford in the spring of 1974. I was a junior at Wheaton and he came to speak in chapel so, it happened that we met in the men’s room. Kind of inauspicious place, but as we were drying off our hands, we chatted and 13 years later we met again in the transit lounge in Hong Kong on our way to Singapore.

I was also mentored during my last year at Wheaton by Don Hoke, who was a congress director for 1974. So, the impact began early but my personal engagement began in 1987 when I was at that congress on the University of Singapore campus. So, there were about 300 of us, I think from 70 or 80 countries, maybe more, I’m not sure. But for many of us, it was our first global gathering. I think the average age was somewhere around mid-30, so we’re typical, ambitious, kind of arrogant, prideful, people wanting to change the world. All of us wanted to be the next Billy Graham, John Stott—whatever the case may be. And we were there. And I think that’s fairly typical of young people and God does lots of things to refine us. He translates that selfish ambition into godly ambition and that pride becomes refined and translates into Christ-imitating humility—hopefully. That’s what was happening to me because as I was there, I thought, here’s Leighton Ford who’s leading this and John Stott and Gottfried Osei-Mensah from Ghana. These were great people and they’re just creatively hanging out with us, younger people. And I saw in them there wasn’t a need to be front and centre. And I began to meet other people who were my age, who were trying to do similar things when we were learning from one another.

I’ll tell you one story, Jason, if I could, you might want to edit this out because it’s a little embarrassing to me, but at that younger leader gathering in Singapore, I met a man from Sri Lanka named Kumar Abraham—we’re still in touch all these years later—he and I were in the same small group, and he was involved in leadership development, leadership training down in the Philippines, and I was involved in leadership training in Japan. Well, one day while we were talking, he said, ‘Doug, are there any young men, young pastors in Japan, who might wanna be a part of our leadership training program in the Philippines?’ I said, ‘that sounds like a great idea. Come on, let me think about it.’ But in the back of my mind, I was thinking, ‘why would a Japanese pastor wanna go to the Philippines to study with a Sri Lankan when he could stay in his own country and study with an American?’

Jason W

Wow.

Doug B

Now, almost as soon as I said that I became conscious of ethnocentricity. A few years earlier when I had gone to Japan for pre-field training, people say, ‘Don’t take your culture with you.’ I thought, ‘How do you take your culture with you?’ You don’t put it in a suitcase or a missionary bureau. It’s in your mind and in your heart. And I realized at that time that the subtext of what I was saying is, ‘I’m better than you. I come from a rich, powerful country. You come from a small war-torn impoverished country.’ And I went back to my room and knelt by my bed and wept as I asked God to forgive me. That was a revolution in my own mind.

Doug B

I realized that an American passport is meaningless. I was discovering what does it mean to be a kingdom citizen? What does it mean to be a person who has lost your life to find it? And so that profoundly changed me and changed the way that I look at the global church and I see the riches of the church in Sri Lanka and other parts of the world that I had never discovered before. I also see the riches of my own country. I see the poverty of my own country. That’s one of the great values of the Lausanne Movement.

And I saw Lasuanne three, the congress in which I was most directly involved as, really, a gift exchange. Let’s come together because you’ve got something I don’t have, and I have something you might need. And maybe there’s something I’m aware of that we could both discover together. So that to me, again, the fact that the Lausanne Movement is a global network of Christ-centred, biblically informed evangelicals who are learning to trust each other and to collaborate and to encourage one another. I think that’s such a gift that we have that we have friends around the world. I think of my friends like Ramez in Egypt, or Susan Perlman in San Francisco, or Lindsay Brown in London, or Blair Carlson in Minneapolis and Hwa Yung in Kuala Lumpur, they’re still going. That gives me the desire to keep going. To be faithful to the end.

Jason W

I’ve heard that you actually spent time with both Billy Graham and John Stott.

I would love to hear how you would define their roles within the Lausanne Movement and also how did you experience them and what lessons did you learn from their lives and their ministry?

Lessons from Billy Graham & John Stott

Doug B

Thank you. Yeah, that was one of the great joys of my life, Jason to meet those people. I actually met Billy Graham also when I was a student at Wheaton College. Actually, I met my wife at a Billy Graham crusade in Chicago when we were 18 years old. We had just graduated from high school and we both lived in central Illinois and the ministers had chartered a train to Chicago for the crusade.

And I saw this really cute girl who I knew was a very committed Christian and a lovely person . . . And four years and two days later we were married. But, it was while I was at Wheaton where Billy Graham was a trustee that I actually met him. He was on one of the committees and they were meeting in the dormitory where I lived.

Doug B

But I got to know him, really, through Leighton Ford initially. I’d been in a mentoring group with Leighton, along with about 12 or 15 other colleagues in mission and church work, and Leighton arranged for us to meet Billy Graham at the Cove, and that’s where I first really met him. But then after I became the leader for the Lausanne Movement, Leighton again took me up to Billy Graham’s home, and we had a wonderful afternoon there talking about many things. And that’s where he and I had a very interesting conversation. And again, I’m just struck with his humility, his graciousness, his sense of wonder at how God had used him all of those years. And while we were there, we talked about John Stott. Billy Graham and John Stott had great admiration for one another. It’s also interesting, it’s not unusual for there to be rivalries among people that God uses greatly. There was a bit of that, but it paled in comparison to the admiration, but that was just kind of interesting to me. But while we were talking, I suggested to Billy Graham, and he liked to be called Billy—although we always refer to him as Billy Graham or Dr. Graham—I suggested, wouldn’t it be nice for you and Uncle John to get together one more time? And I shared that with John Stott and they were both very excited about that possibility and that had all been arranged. John Stott was going be preaching at a conference in Atlanta and he was gonna fly up to Asheville. Unfortunately, before that happened John Stott had a fall and broke his hip and was not able to travel internationally again.

Billy Graham The Spirit of Lausanne

Doug B

But as Billy Graham and I were talking towards the end of our meeting, I said, ‘I’ve heard many people use the term, “the spirit of Lausanne” over the years, but I wonder how would you describe that?’ And that was the highlight of the meeting for me because even though his eyes were dim and his hearing wasn’t real good, his hands went up and said, ‘The spirit of Lausanne? Why, it’s a spirit of humility and friendship, study and prayer, partnership and hope.’ Well, I want to remember those words. And as Leighton and I were driving down the mountain later on I said, ‘What, how, what was, what were those words?’

Humility and friendship. Study and prayer. Partnership and hope. I’ve shared that hundreds of times in years since, and I’ll always ask . . . it’s interesting. It begins with humility, and it ends with hope. So that was a great meeting there with Billy Graham. He asked me to go in and say hi to Ruth. And Ruth was not in good health. She was in her room watching television and I went in and I thanked her for her life and her faithfulness to Christ, and her service to her husband and the church around the world. And she said, ‘I just tried to be faithful’, and she certainly was.

The Influence of John Stott

Doug B

Well, with John Stott—so many things. He was actually the first person that I called in 2004 after I became the chairman. And I asked him if he would be willing to serve as the honorary chair. And he said, ‘You don’t need an old fogey.’ I said, ‘Absolutely not. We would not want an old fogey in a role like that, but we would like an older, wiser godly man who’s familiar with the history of the movement.’ And he said, ‘Please let me think about it.’ He asked me to send him a letter with my expectations and he made it clear that he wouldn’t be able to travel, didn’t wanna be involved in fundraising. That was fine, but he said, ‘I would like to be kept informed.’ So that gave me the great privilege to call him periodically—frequently. I tried not to call him too often, but he really loved to talk about Lausanne, and he always had something to share. So, there were so many lessons that I learned from him.

One time I was driving from a foundation office in Kansas City back to the airport, and I just called and gave him a little update on some things that were happening. And towards the end of the call I thanked him again for his friendship, his wisdom, and for all that he had done for the global church—for his lifetime of service. And he said, ‘Thank you, Doug. That means a lot to me. And I appreciate your kind words, but I just try to be faithful,’ and then he said, ‘and I haven’t done much.’ But I thought, ‘That’s not false humility.’ He realized that he was a privileged person in many respects by virtue of where he was born, when he was born, his education . . . but he was a godly man.

Just one little last story about the two of them before Cape Town. We wanted both of them to write a letter to be included in the program book. And, I think, we also taped an interview with both of them. But : Lindsay Brown and I were with John Stott where he spent the last two or three years of his life, the College of St. Barnabas, an Anglican Retirement Community outside of London. Two things were interesting about that. While we were there I asked him, I said, ‘Are you happy here?’ Because he spent all of his life in Central London. And there again, as Lindsay and I were both in our mid-fifties, and here’s John Stott in his eighties towards the end of his life, and he said, ‘I wouldn’t say that I’m happy here, but I am learning to be content.’ Now, all of us will eventually get old. And I thought, what a wonderful lesson to tuck into my mind and my heart, but to be content: godliness with contentment. It was great gain. And I saw that in John Stott, not in a book, not in a conference platform, but in a bed, in a retirement home. I’m talking about, I am learning to be content. When I asked him for the letter he said, ‘Have you asked Billy?’ And I said, ‘Yes, we have.’ He said, ‘Well, I would like to see his letter. He’s the founder. He should have the first word. And then I will seek to add to it.’ Well, both letters were like gold dust and so much appreciated. So yeah, those are just people that were uniquely gifted. People referred to John Scott as a 15-talent person. Billy Graham was one of the greatest Christians and the 2000-year history of the church. Not just one of the good guys of our time—a truly epic making man.

And so, for Lausanne to have that heritage, and not only to read the documents, but how do you capture the spirit and again, the spirit of humility. And I’ve discovered through my interaction with these people that humility releases power. Oftentimes there’s a pride that wells up with a younger leader or any leader that, ‘I’ve got this position, I’ve got influence how can I demonstrate it?’ And you can unintentionally, or maybe even knowingly, make people feel inferior when there is a sense of, well, you could do that. I’m just trying to be faithful to my job. It is empowering and every time I left a meeting with either of those people, I also want to mention Leighton Ford and Gottfried Osei-Mensah—equally great people who are wonderful, who were used to give a Movement life.

This is how I often describe it, Jason: Billy Graham, in a sense, was the person who gave it life. God used him to convene and to catalyze a movement. God used John Stott to give definition to the Movement through the Lausanne covenant. God used Leighton Ford to give organizational and global leadership to the movement. God used Gottfried Osei-Mensah to give it a global presence. A young, winsome, brilliant engineer, pastor from Ghana, and I think he also served in Nairobi, but travelled the world. And so those were the four people that God used in great ways.

Jason W

They indeed were legends and they have really impacted the legacy, not only of Lausanne, but of global mission and global Christianity. I also want to take some time to move a little bit closer in time and become a little bit more a part of your story, because you have also built a legacy and been a part of the legacy of Lausanne and global mission and global Christianity. Specifically, you were part of establishing the Cape Town meeting in 2010. I would love to hear from you some reflections on the Third Lausanne Congress in Cape Town in 2010 and how it set the course for the movement’s ongoing mission.

Reflections on the Third Lausanne Congress in Cape Town, 2010

Doug B

Thank you, Jason. There again, that’s a God story and it begins in a library in Oxford. The Bodleian Library where I was studying one night on a Saturday in January of 2004, and I was reading documents about Lausanne history. That evening I was reading several articles that had been written in 1984, 10 years after the congress.

They were retrospective reflections on that great congress, and I was deeply moved. I was doing PhD studies at the Oxford Centre for Mission Studies, so it was serious study. But not only was my mind informed, but my heart, you might say as Wesley would say, was strangely warm. And as I was reading those articles, I just began saying, ‘Oh God, do it again. Do it again. In our time. I don’t wanna just study history. I wanna be a part of your work in history. I wanna do something for your glory that might once again unite and energize strength and purify the church.’ And after a while I realized I couldn’t really concentrate on my studies, so I packed up my books and my computer bag and I walked over to the courtyard at Christ Church there in Oxford, and I just sat there on that beautiful winter night and just prayed, ‘God, do it again. Do it again.’ And when you pray like that, you also say, ‘I’m willing to be available any way that I can.’ Well, two weeks later I got a call from Paul Cedar, who was the chairman asking me if I would be willing to have my name put forward to be the new chair. And I told him that I was honored to be asked, but I really felt that it should be a majority world person. It eventuated in my being appointed a few months later. And as you may know, that was a kind of a challenging time for Lausanne. Movements, like most institutions, have ebbs and flows and we were actually in Pattaya for the 2004 forum, which Paul Cedar and Roger Parrott and David Claydon gave great leadership to. That was really a part of the revitalization of the Lausanne Movement and that’s when I first proposed the idea of a third congress in Cape Town in 2010. For one thing, it was the 100th anniversary of Edinburgh 1910, but more important than looking back, was looking forward and I was concerned that missions had become too driven by, some would say, leadership priorities, managerial efficiency, a checklist . . . do these kinds of things, many of which were important but theology had faded, and I thought, the Men of Issachar understood their times and they knew what Israel should do. That was theological reflection for studying history and culture and the work of God and their society. So, I thought in a sense there’s theology and strategy right there.

The men of Issachar understood the times and knew what Israel should do. About a year later I convened a conference call. There were 25 people on that call and they were among people that I knew or knew of for whom I had great respect. And I just said, ‘Do you think that a third congress might be useful?’ I didn’t really begin with that. I said, ‘There are some big challenges that we are facing in the world today. And there are some challenges that are being faced by people all over the world. Many challenges are local challenges. Some are national challenges, but there are some that are truly global challenges.’ Well, those people were really enthusiastic and supportive. We had another call two or three months later at which time I asked them to serve as an advisory committee. Many of our Congress leaders came out of that group. And then as I began traveling, talking with people wherever I could find a Lausanne ember, I would blow on it to use them to try to find a flame and bring them together to build a fire. And that did happen. There were many people who were Eager for such a congress.

By 2007 we had visited, those of us in leadership, over a hundred countries around the world. We were asking similar questions and we had a meeting in Budapest. It was very interesting. We had 300 people, or something like that. But we met for parts of five days around tables and we discussed issues that we thought were of global significance. Well, some folks from the Oxford Centre for Mission Studies, a man named David Adams, took all that data back. We wrote on table cloths and we folded the tablecloths up—they were made of paper—and they digitized all of that, analyzed all of that. And interestingly, there were six issues that were mentioned over and over, like they were really top tier, there’s just no question. These were the issues that everyone was talking about.

Well, those six issues became the primary issues around which the Congress was built, and interestingly, in 2009, I was in the Vatican to meet with the cardinal in the Pontifical office of Christian Unity, to ask if they would send a delegation. And as I was talking with that cardinal, about the second or third time I had mentioned the six issues, he said, ‘What are the six issues?’ Well, I could rattle them off back then. And he said, ‘Slow down, I want to write them down.’ So, he was writing them with a pencil on a legal pad and it seemed so interesting to be in The Vatican using the same pencil that a guy from Peoria would use. But he wrote down the six issues and then he said, ‘We’re dealing with those same six issues.’ He said, ‘We would be very happy to send a delegation, but we would like to participate with you because we’re wrestling with these same issues.’ So at Cape Town those issues became front and center and the last day that we were in Budapest in 2007, the five of us who were on the leadership team—I just mentioned Lindsay Brown, Blair Carlson and Ramez Atallah and I— and at the end of that meeting, my dear friend Lindsay Brown, who had IFES for many years, he just said, ‘This is so exciting’.

He said, ‘People are going to be salivating, wanting to come to Cape Town’, Well that, and then three years later to be in Cape Town with 4,200 participants and over a thousand staff and median stewards and volunteers. I remember walking around the commission like, ‘Where did all these people come from?’ But God was honoring the vision and the legacy, the persevering work of folks, and we just happened to be there at that time and were wonderfully blessed in the process.

Jason W

And I know that many others were blessed because of the 2010 Congress. I personally studied the Cape Town commitment in seminary and thank you for all that you did, for putting that Congress together.

I’d like us to take a moment just to look forward. We are now on the precipice of hosting the Fourth Lausanne Congress in Seoul 2024.

And I would love to hear from you, what is your hope as you look forward to the Seoul 2024 Congress, and what would be your hopes and your prayers beyond that for the ongoing mission of God and of the Movement itself?

Looking Ahead: Seoul 2024 and Beyond

Doug B

Thank you. Jason, and it is something we think about a lot and pray about a lot because it’s an enormous challenge to pull it off. But it’s a great privilege to be a part of it.

When it comes to Lausanne Four in Seoul, it is interesting now to be 70 years old. Not that old, but not involved in the planning or the leadership. So, I’m rooting from the sidelines just as my friends and predecessors are doing and have done for us. So, it’s generation to generation seeking to be faithful and honor our predecessors, support our successors. So, we really are praying that God will bless Michael Oh, and David Bennett, and Patrick Fung, and Hwa Yung, and many others who are working with them to organize this great Congress coming up in Seoul just a year from today, it begins.

My hope is that it will reinforce this sense of being one as the people of God. We have a problem here in our country with the people who are too taken with celebrity status. I think that’s fuelled by social media. And so I think for the church to come together to hear the word of God to be refined—and the refining fire purifies and strengthens and sharpens the steel— So, for us to have a greater sense of oneness, for us to have a greater sense of clarity in what the issues are, for us to have the courage to tackle them and the humility to collaborate with others on them. The world is very different in 2024 than it was in 2010. It’s hard to imagine the changes that have taken place and the leaders of Congress two, where I was involved, also said there’s no way we could have anticipated what happened just a year later with the collapse of the Soviet Union and how the world changed there. So, there are these epics in world history and there are also epics in church history. When we were having the opening ceremonies in Cape Town, it was a glorious celebration. I think the closing ceremonies were even more glorious, but there was a video that was a part of the opening ceremonies with four segments, and they were segments of world history and in each of the segments, they began with the sun rising over the Serengeti desert. And they were then synchronous with renewal movements that were taking place in the church, but each of the periods ended with the sun setting. And the church had gone into a time of darkness and crisis. And the moderator, the narrator rather, ended each section with these words: ‘And they thought it was the end of the world.’ Well, we are, I think, at a difficult point in world history. We’re plagued with global problems in the environment where I believe Christians have responsibility, political, economic, confusion about gender worries, about artificial intelligence, the decline of the church in the west. And some of them might say, ‘It’s the end of the world’, but God uses—the light does shine brightest in the darkness, and it’s often at these times when, in ways that we didn’t even know, this 2024 Congress was in the mind of God before he even created the world. And it may be that God uses this in a powerful way to bring renewal.

We saw just a little spark, a powerful spark, a bright flame of the presence of the Holy Spirit on the campus of Asbury College and seminary just a few months ago. And perhaps that spark as it goes to Seoul, along with people coming from other parts of the world, will ignite something truly wonderful that will inflame the hearts of God’s people with a passion for God and the courage to take it to the world. So, that’s my hope for Lausanne Four, Seoul 2024.

Jason W

Thank you, Doug. That’s a hopeful and inspiring vision for the future as we close off this interview. I’d like to go back all the way to 1974. Billy Graham delivered his address to the Congress entitled ‘Why Lausanne?’ And he really just gave a vision for what Lausanne was meant to be.

Taking inspiration from Billy Graham, how would you answer that question today? Why Lausanne?

Why Lausanne?

Doug B

Yeah, well, obviously Billy Graham was passionate about Jesus Christ and the cross, and the gospel, and wanted to make sure that we would proclaim Christ until he comes. ‘Let the earth hear his voice.’ That was the theme of that Congress. And so, the Movement is the Lausanne Committee for world Evangelization.

So, world evangelization, the proclamation of, the demonstration of the gospel is uppermost, and we need to be reminded of that. And we need to meet and see and hear from people who God is using in a powerful way. So, one is to be reminded of the centrality of our mission in the world. Number two is to meet people who God is using. And number three is to trust the work of the Holy Spirit, to bring people together as he does, as he has in all of these gatherings.

People who meet in the registration line, or on the bus from the airport to the hotel, or over lunch. When you put 4,000 or 5,000 people together in the same room and the Holy Spirit is there going way beyond what the very talented team has planned, miraculous things happen. And so, I would say, for the glory of God, for the good of the gospel, and for the heartbeat and the heartache of the world we need Lausanne to provide impetus to provide some coordination, to provide ongoing strength of leadership for individuals, churches, denominations, colleges, seminaries, heritage societies that have the courage and have the will to make a sacrificial commitment that everyone would hear of the goodness of Jesus Christ to envision the certainty of his eternal, victorious rule and reign over all that he has made.

Jason W

Wow. Thank you for that. And on behalf of the podcast listeners and on behalf of myself, I just want to say thank you for all that you’ve done for the global church. We are all standing on your shoulders. Thank you for your time, you’ve added value to all of us as your listeners. Thank you.

Doug B

Thank you, Jason. It’s been a pleasure. God bless you.

Jason W

Well, that wraps up a conversation with Doug Birdsall, a man whose dedication and leadership have significantly impacted the Lausanne Movement and global evangelization. Doug, thank you for sharing your journey with us and for your unwavering commitment to the global church.

Next up we have Ramez Atallah.

Ramez served as the general secretary of the Bible Society of Egypt and as a regional secretary for the Middle East International Fellowship of Evangelical Students. He has participated in the Lausanne Movement since its inception in 1974, twice serving as vice-chairman and was the program chairman for Cape Town 2010 Congress.

Ramez shares insightful stories from Lausannes 50 year legacy that both encourage and challenge.

Let’s hear from Ramez Atallah.

Interview: Ramez Atallah

Jason W

Ramez, welcome to the podcast. Thank you for joining us.

Ramez Atallah

Thank you, Jason. It’s a privilege to be with you this morning.

Jason W

So, in today’s podcast episode, we are exploring the legacy and the impact of the Lausanne Movement. And the reason we are interviewing you is because you are a living legacy. You attended the very first gathering that Billy Graham put together in 1974 in the city of Lausanne. Could you share with our listeners, how you became involved in the Lausanne Movement and what has kept you connected and committed to the movement?

How did you become involved in the Lausanne Movement?

Ramez Atallah

In the early seventies at seminary, I met Leighton Ford, who was a brother-in-law of Billy Graham and one of the trustees of Gordon-Conwell Seminary, where I was studying. My friendship with Leighton is the main reason I’m involved in Lausanne. He probably was the person who put me high on the list of people to go to the ‘74 Congress.

But I had a problem. I was a student worker. I didn’t have enough money and it was expensive. So, I wrote to one of the people in charge, the program director, Paul Little, and said, ‘Look, I can’t afford to pay that amount,’ and I also complained that they didn’t have anything about our relationship with Catholics.

So, he asked me, he told me, ‘Look, we have a seminar, but nobody wants to take it. If you take it, we’ll pay half your way.’ The seminar was on evangelizing sacramentalist Christians and by that, they meant Catholics in that day. Not a very good choice of a name. So, I accepted to become a world expert on Evangelicals and Catholics and for three weeks I worked very hard. My boss at that time was Samuel Escobar, one of the speakers at Lausanne, and he helped me very much. He was from Latin America. I was working in a Catholic context in the province of Quebec, and he was, used to be, from Peru so he knew the situation well.

Anyway, that’s the reason I went to Lausanne and could afford it. But just in a bracket, I hated that title. So, if you pick up the compendium, you will see ‘Evangelizing Hindus’, ‘Evangelizing Muslims’, and when you come to the Catholic one, you’ll see the title of my paper saying ‘Some Trends in the Catholic Church Today’, and then it goes on to evangelizing such and such.

And, later, we can talk about what I felt about doing that seminar at Lausanne. But I was the youngest seminar leader at Lausanne and that is why it was probably one of the reasons why I was chosen to be the youth representative on the Lausanne Continuation Committee, which was established with 50 of the leading evangelicals of that day, right after the Congress.

Jason W

One of the things that I found so meaningful about your story is that you, as a young leader, had the opportunity to be at this amazing gathering in 1974. I would love for you to share with us some of the memorable moments that stood out to you from that gathering that may in some way inspire those who are listening.

Inspirational Moments

Ramez Atallah

Well, many of the things that evangelicals do today and they feel is natural for evangelicals to do or to be concerned with were not so in ‘74. The main emphasis of evangelicals at that time was evangelism in its narrow definition and it was not seen as being the mission of the church, particularly, to reach out to social issues or social concerns.

As a matter of fact, in 1972, John Stott was interviewed in Canada and the interviewer asked him, ‘Dr. Stott, what do you as a Christian minister think about abortion?’ and he said, ‘I’m a minister of the gospel. I don’t comment on social issues’.

By 1974, Johns Stott had changed and he said very clearly in his talk, which was a pivotal, very controversial talk at the Congress, that the mission of the church is both the evangelization of the world—the Great Commission—but also the practical concern ‘Love your neighbor as yourself’, for people. So, we have two missions. To evangelize and to love and serve people and that was very evolutionary and one of the most controversial issues in the early years of Lausanne and one of the reasons, it’s not called the ‘Congress of the Lausanne Movement on Evangelism’, it was called the ‘Lausanne Congress of Evangelization’, meaning it embraced a broader concept than simply telling someone about Jesus verbally.

At the Congress, there was a lot of controversy. One of the brilliant speakers was Malcolm Ridge. He was not an evangelical and he introduced Mother Teresa to the evangelical world. A Catholic nun being the focus of evangelicals was not habitual. And that was a paradigm shift.

Also, John Stott in his talk I just mentioned, and then, Padia and Escobar, two of the Latin American speakers, were very critical of evangelical missions and how there was some fallout, negative fallout, from evangelical missions over years, and they spoke representing the third world, in very strong terms.

Lausanne became more radical and was able to bring in younger generation of evangelicals who were discouraged by the elders who they felt were not really facing the world and the issues of the world as evangelicals and so Lausanne was a breath of fresh air to hundreds of thousands of younger evangelicals worldwide through the publications that came out after the congress.

Jason W

That covenant captured the imagination of the evangelical world. It took the world by a storm, it united evangelicals worldwide.As you look back, can you think of any other pivotal moments that you believe shaped the direction, the mission, and the vision of the Lausanne Movement from that 1974 gathering?

Most impactful moment in his life

Ramez Atallah

Well, I think John Stott, René Padilla’ and Samuel Escobar’s talks were controversial and therefore attracted much attention and discussion and brought into the evangelical agenda things that were not . . . I mean, Stott changed in two years from where he said, ‘I’m not concerned about abortion’, to a few years after the Congress writing a whole book on issues facing Christians today, in which he dealt with all the social issues that were then on the table.

So, people changed and the covenant, in a sense, addressed and infused a generation of evangelicals who went on to have a great impact. But to tell you a story, a very different story, the main thing I remember from Lausanne was on my way back in the airplane looking through the business cards of the people who were in, I had the people who I had met, but mainly those who were in my evening prayer group.

We had about 20 people, and we prayed together every night, and one man was a pastor from Kenya, and he was wearing one of his Kenyan robes, you know, a white robe. He looked like a village pastor. He said he began his life as a village pastor. He was very humble, and he was very wise, and we’d reflect on the day, and I was impressed by what he said.

And I told myself, ‘Isn’t it strange that such a simple village pastor is so wise?’ The other people were saying they were presidents of seminaries, directors of this, that and the other, and were pulling rank. Festo Olang’, that African pastor, never did that. We never knew exactly what church he was working with or anything.

So, as I was on the plane going back to Canada, I was looking through these cards and I looked at his card, and it has impacted my life since then.

It said: ‘Festo Olang’, Archbishop of Kenya’.

Jason W

Wow. Wow.

Ramez Atallah

He was the highest-ranking guy by far of all of us, and we never knew it, and I said to myself, ‘I want to be, I want to be like this man when I grow up.’

Other impactful moments?

Jason W

I can imagine that being involved in that gathering as a young leader must have been truly impactful. As you reflect on your life. How do you believe the trajectory of your life shifted because you had the opportunity as a young leader to be a part of that gathering?

Ramez Atallah

Well, it was after Lausanne that I was more impacted because I was part of this committee of 50 people who were the leading evangelicals in the world. And I was at least 15 to 20 years younger than the youngest. I was out of my league completely. I mean, all of them were very key, well-known people. I was not known. I was very young and to be on that committee was an incredible privilege and I learned a lot from some people. I learned what I wanted to be like from some of them, and what I didn’t want to be like from others.

It was very difficult for these people to get along with each other. They’d never sat at the same table. They’d never done anything together. They were entrepreneurs, visionaries, many of them each running his own organization. Lausanne was the first gathering in ‘74 that brought charismatics into the evangelical. Before that, the word ‘evangelical’ was in contradistinction to charismatic and to mainline.

So, you had the mainliners on the left, and you had the charismatics on the right, or the opposite way, and evangelicals were somewhere in between there. Lausanne had people from mainline evangelicals in mainline churches, like John Stott. And it had charismatics like Tom Zimmerman, the head of the Pentecostal World Alliance who was also general superintendent of the Assemblies of God in the United States.

Well, sitting at the table and listening to these men, and a few women, talking about these issues was incredibly enlightening, incredibly challenging, and it impacted my life. Tom Zimmerman, who was the sort of pentecostal who we thought would be jumping up and down, raising their hands, and speaking in tongues, wore a three-piece suit and had a watch—not a wristwatch—one of those watches, you know, you put with a chain in your vest. He looked like a businessman, like a bank manager. A completely different image than what I thought would be the head of a worldwide Pentecostal Movement.

He was extremely wise and he brought Pentecostals into mainline Evangelicalism while working on that committee with Leighton Ford. So, that was very significant. John Stott brought the more mainline evangelicals. Before that they had not worked together, ever. And then the parachurch organizations, which were very entrepreneurial from YWAM, to Operation Mobilization, to . . . All of these had never worked together. And one of the most moving things from the Congress was Operation Mobilization was raising money to buy another boat. They had the Logos ship, where they went around evangelizing and they were raising money and they were not doing too well. Youth with a Mission had raised money for a boat, but they hadn’t yet bought one.

They didn’t. It was going to be a new mission and so the leaders of Youth with a Mission decided to give that money to Operation Mobilization to buy their boat, and they would wait for their turn. That was what happened at the Congress and for two groups, one being charismatic, and one being maybe ‘anti-charismatic’, to have that kind of love and fellowship made a big impact on the Congress itself.

Jason W

Wow. That’s truly amazing. Especially if you consider that Operation Mobilization are still operating the ship. They are still going around the world preaching the gospel. I personally have a few friends that are on the ship and the stories that I’m hearing back are just amazing. And that happened because 50 years ago there was this idea of unity and collaboration. And we’re going to touch a bit back on that a little bit later in the interview, but I want to shift just a moment to chat to younger leaders. What advice would you give to a younger leader listening to this podcast? Maybe they are missionaries, maybe they’re in church work, maybe they’re in work placement ministry. What advice would you give to the next generation?

Advice to young leaders?

Ramez Atallah

Lausanne presently is focusing very much on intergenerational meaning. It’s not just the younger generation that we focus on, but we mutually benefit from one another. So, my first message would be, learn from your elders, like I learned from listening, so that as you get more responsibility, you have more experience and wisdom.

I used to carry Leighton’s books and files around for him. I made the reservations. I did a lot of what you may call ‘the dirty work’ in Lausanne. We had no staff, so the chairman and I were doing a lot of—I used to do all the reservations for all the conferences, the places we went to meet as an executive, and I attended every executive meeting.

So, don’t feel you need a position as much as to be alongside all the people who are more experienced than you. So, that’s my first suggestion. But the other advice would be to the older people to take a risk with the younger, and at that first committee meeting in Mexico City in January of 1975 as I looked through the minutes about five years ago, I noticed that I had led the devotions on that Wednesday night. I had completely forgotten, and I think I must have been crazy to accept to lead devotions with that group, and I don’t know why I did it. But someone risked. Someone went out on a limb, and I have an idea who it was and put my name there.

So, hang around people who are more experienced. Don’t look for position, or clout, or prestige, but as you faithfully are there, God will open doors for you that you couldn’t ever imagine could be open.

Jason W

And I would imagine that that risk was actually less of a risk and more of an investment into you as a young leader considering if we fast forward just 30 years you became the program chair of the 2010 Cape town Congress. I would love to hear from you, what stood out to you from that gathering? Were there some specific milestones that you reached? What do you believe made Cape Town 2010 unique to the previous two gatherings Lausanne has held?

2010 Congress

Ramez Atallah

As I mentioned to you earlier, it’s a bit difficult because I was the program chair. But it was very difficult to plan a program that would please the many stakeholders of Lausanne, who are plentiful. And I knew from the first that I wouldn’t be able to do everything I wanted to do, so I decided to be the architect, not the contractor. That is, I put a lot of effort into the structure of the Congress, put in a lot of my own opinions there, and left others more powerful—the stakeholders—to fill in the slots of who should speak.

I knew it was too politicized for me to get onto that bandwagon, but the things that were unique was that we studied one book of the Bible, Ephesians, presented by different people—including two women—in the six days we were there. So that was a unique thing. The other thing is we had chosen six of the major topics, it was very hard to decide which were the major topics, that concerned evangelicals and use them as plenary times.

But the unique thing was that the Bible teachers had 25 minutes and the main plenary speakers for these issues had only 15 minutes, and then we divided into groups with questions. We had 800-and-some groups, of six each to discuss what they heard. The argument was everyone around that table was a leader. Maybe some of them knew more than the speaker who just spoke for 15 minutes. Just because that speaker was very well known didn’t mean that some of the leaders . . . so at those tables you could learn just as much from people at your table as you could from a speaker. And that was extremely unique and very daring.

And we had some well-known speakers who turned us down and said, ‘I’m not gonna come to Cape Town to just speak for 15 minutes’, but those who did, we very much appreciated the humility to do that and, I think the impact, one of the most positive things of the of the Congress was people felt they were not simply listeners, but they were participants, because they were eager they were actively engaging for a lot of the time with their colleagues on the issue. They could share, they could discuss, they could . . . so they were not just sitting recipients, they were active participants. So, when you have five, 4 to 5000 people that are active participants, that makes people have ownership.

The other thing we did, in addition to the six big topics, we had many other topics that were very controversial, but very important. So, we have 18 what we call multiplexes, large sessions in the afternoon. Some would be as many as 2000 people. The handling of 18 of the major issues that evangelicals had raised as we did surveys, and studies, and so on; ee couldn’t make them plenary, but we made the multiplexes. So, it wasn’t just a seminar, it was a presentation, one and a half hours, with a presentation of an hour, let’s say, with half an hour of discussion. It was very engaging and dealt with nearly every major issue that evangelicals in 2010 were concerned about. And then, in the evenings, we did what most congresses did. We had testimonies and stories from around the world.

The most impactful talk was maybe a five-minute talk by a young, young girl in her teens from North Korea who talked about how her family suffered. She was brilliant. She moved us to tears and if you ask anybody now, so many years later, they say they remember that young Korean girl’s talk. It was quite a moving one.

Jason W

Remez, could you share with our listeners any stories of transformation that resulted out of the gathering, or perhaps because of those table groups?

Misisons organizations unite

Ramez Atallah

In Manila two things came out that became very key in Lausanne, the Forum of Bible Agencies. The Bible is our most important book. People who produced the Bibles and translated didn’t get along together. They didn’t know each other. They were all doing their own little things. Wycliffe Bible Society, other organizations who do the Bible Biblica, they weren’t cooperating. Fergus Macdonald, who was at the Congress, who was the head of a Bible Society in Scotland, brought together all the Bible agencies at this Congress in Manila. And that Forum of Bible Agencies has been going on since 1989, helping these evangelical organizations that work on the Bible to work together. That’s the main one.

The other thing that came up also, in the 1980 consultation, not the 1989 one Arthur Johnson attended, was the focus on cities. A man called Ray Bucky visited a hundred cities before that consultation and set up committees that would work on thinking of reaching the city, the mega cities. And this whole thing of reaching cities came out of that consultation, 1980 with Ray Bucky, his great vision. He’d been to more cities than any person probably in the world, and he’d made contact with the Christians there.

So, these kind of impacts were palpable. You could feel how that changed. It was a paradigm shift. The same happened with the youth ministries in the universities—Campus Crusade, all the YWAM, and so on. In 1976, the Olympics were in Montreal. We had a committee of 50 Christian organizations that had come to the Olympics to evangelize. We met at the ‘74 Congress, say, all of us who were interested in doing something at the ‘76 Olympics. So, we got to the ‘76 Olympics and every single booklet, whether it was a ‘Four Spiritual Laws’, or somebody else’s particular tract, had the logo of the organization, but also the logo of Aid Olympic, which was the Lausanne umbrella organization.

So can you imagine when you have 50 organizations giving out literature with the same logo? People felt it was one organization. I represented this in City Hall, so I represented Aid Olympic to the government of Quebec and we attended meetings, as though it was one organization, you see. And on the last day, the lady who was chairing it said, ‘We have to clap for Mr. Atallah because his organization did more for the city than any other organization.’

Jason W

Wow.

Ramez Atallah

Now that wouldn’t happen if it wasn’t for Lausanne and, of course, they gave me the credit. It wasn’t my organization. I just happened to be working in Quebec at the time, and I spoke French. So, they asked me to represent the Aid Olympic.

I could tell you good and a bad story. I was sitting in a meeting in Florida. I don’t remember why, or where, or what. I went to so many meetings because I was helping Leighton. I went to just about every meeting that Lausanne had in the seventies and early eighties. That was a a lot of meetings. Anyway. we were sitting at the table where a Baptist pastor, he was on the Lausanne committee, was very excited and he said he wanted to pull rank. ‘So,’ he said, ‘my church just passed its annual budget and it topped a million dollars.’ So of course, you had pastors from the third world, you have different people. A million dollars in the early seventies was a lot of money and everybody was very impressed except for one person, Tom Zimmerman, the Pentecostal. He was older and wiser and didn’t like this at all and so he said, ‘Yeah, that’s very impressive. My denomination met last week and we passed a hundred million dollar budget.’

That Baptist pastor never spoke again,

Tom Zimmerman was a very humble man. He never pulled rank, but he was mad. And so, he decided to put this guy in his place. So, as I watched this, I realized the dynamics. He is a Baptist who doesn’t recognize Pentecostals being rebuked by a Pentecostal for having been proud. The man who could have pulled rank on all of us, Tom Zimmerman . . . You know, when I planned all these meetings—I told you I planned the meetings for the small committees and so on—so I would have to know how many people were coming. Tom Zimmerman would always say, ‘Don’t forget my pilot’, because Tom Zimmerman came in his private plane. He didn’t come like all of us by public planes. He had his own private plane. He was too busy, you know? So, this man was so humble you didn’t feel at all that he was proud of what he did or would pull around. So, you learned humility from a man who could outrank all of us.

You know, and I’ll give you another funny thing. He invited us to Springfield, Missouri for one of the meetings in his big conference center and John Stott was there, a very stayed Anglican, you know? And you have to realize that in those days, all the worship songs you would now see in Anglican churches were only seen in Pentecostal or semi-Pentecostal churches. When you hang out, you sang the hymns of the faith in evangelical churches. So, he said, ‘We’re gonna have a special night,’ and John Stott was sitting on the front row and we all looked at him, you know, as he quietly clapped along with these people who were jumping up and doing. But it was a cultural experience, you know, it broadened Stott’s view of Christianity and how we’re different people, and we enjoyed it. It was fun to see the mixture of people.Anyway,I can go on and on of perspectives, positive and negative over the years.

Jason W

I’d like to take a moment just to pivot a bit from the past and begin to look more towards the future. As you consider the future of global mission, what do you believe are the greatest challenges that lie before us, and the greatest opportunities, and how do you believe Lausanne could play a role in that? And more particularly, how do you believe an individual believer could take part in the future of global missions?

Looking forward – missions in the future

Ramez Atallah

I think Lausanne is not a mission agency. It’s not a group with an agenda. It’s a group that brings leaders together for ‘iron sharpening iron’ so that they can grow and be more effective in their ministry rather than Lausanne Ministries. So, Lausanne is an umbrella organization. The thing that happened at the Olympics, Lausanne was not involved and they didn’t fund it anything, but they provided the umbrella under which all these groups could work.They could never have worked together under any other umbrella, but Lausanne provided that umbrella, and got some credit for it maybe. But the hard work was done by the organizations themselves.

So, I look to Seoul 2024 as an umbrella again, that people who are living close by each other, or are having same ministries and have never benefited from the wisdom and experience of others who happen to be in a different ecclesiastical grouping than they are, will benefit. I hope there will be small groups. I hope people will benefit from each other. I hope there will be a concern about this new concept of intergeneration. We’re not just focusing on young people—good—but we have wanted these young people to learn from the older people and the older people to also learn from the young, you know.

I’ve learned a lot from people much younger than me in my ministry and life, and brilliant people, what they’re doing I could never do. So, I’m hoping that, I hope we’ll have more women speakers. I hope we’ve gotten over that hurdle. It was not easy in 2010 to have two women speaking in the Bible teaching, I hope it’ll be easier and in other areas, women are more than half of the evangelicals in the world and are probably doing more than half of—much more than half of—the work. So, I think that.

I think the other big issue since then, since ‘74, but maybe even since Cape Town 2010, is personal integrity. I think one of the reasons we’ve had failures with evangelicals in their integrity is because of a concept of success being numerical success, or publicity, or being famous. You know, becoming famous puts pressure on you that makes you forget your moral compass. That’s the only way I can explain why people, really respected people even in Lausanne, have had moral failures. Bad moral failures, you know? And I think it’s because you think you’re so important and people need you so much, and you’re doing so much for the world that you neglect the fact that you’re a sinner. And so, anyway, focus on that.

Elisabeth Elliot, who’s one of my heroes, you know her husband was killed by the Auca Indians in 1956, she says, ‘God has never called us to success. He has called us to obedience.’ Success may be a product of it, but our goal is to be obedient, and I’d say to young people and to others, that should be your goal.

At one point when I was on the youth committee planning the 1987 Younger Leader, I was a program director at the point of that coms meeting in Singapore. And one younger leader said, ‘Unless you have 200 staff in your organization, who are working for you, you are not a leader.’ I had a part-time secretary, she worked two days a week and he said, ‘You’re not a leader unless you have 200.’

I think I look back to the 1980s when I was just working as a student worker in Egypt with that part-time secretary. The fruit of those years is much greater maybe than when I had 220 staff at the Bible Society. So never underestimate what you do one-to-one, investing in people. My greatest contribution in life, my greatest pleasure, is to have invested in people who have gone way beyond what I expect of them and way beyond of me. One of these men, I have to make an appointment two weeks before to go to his office. He would never have time to visit me, and he’s about 15, 20 years younger than me. And at the time that I was giving, investing in him, I thought he was a loser. I didn’t think he would ever make anything. Now he’s one of the best-known leaders around in Egypt, so don’t underestimate the one-to-one. Don’t run after fame. Try not to become an icon.

Leadership is different than being an icon.

Jason W

Ramez with that word of wisdom. I would love to close this interview by just asking you to pray, to pray for our listeners, whether they’re ministry leaders or workplace leaders or church leaders, could you pray that the gospel would be advanced in and through our lives?

Prayer

Ramez Atallah

Gladly. Father, I thank you for the impact people have had on my life, and what Lausanne has meant to me over all these years. I wouldn’t be where I am if it wasn’t for that wonderful fellowship that I experienced. I pray the same experience for hundreds and thousands of young people around the world.

Young people, some of them will be at the ‘24 Congress, but even those who won’t be there, those who will be watching it online, those who will be benefiting from watching the talks. I pray for each one of us, not that just them, that you may help us to be faithful to you and to trust you for the results. To not want to make ourselves indispensable, but to try to be always making ourselves as servants—dispensable—and investing in others so that the future, maybe our goal will not be present.

In Jesus’ name, amen.

Jason W

Amen. Ramez, with that closing prayer I just want to say thank you to you. Thank you for the time that you’ve given us in this interview the investment that you poured into myself and our listeners. As a younger leader I want to say thank you for all that you’ve done for the kingdom of God. We are standing on your shoulders

Ramez Atallah

Most of what I learned has been through mistakes. You know, I wish I could live my life again. It’d be very different if I knew then what I know now. I tried to learn from others’ mistakes so I wouldn’t repeat them, but I did a fair share of my own.

Jason W

Thank you for that final word, Ramez. God bless you and your ministry.

Ramez Atallah

Thank you, Jason.

Jason W

And that brings us to the end of today’s episode.

If you found value in today’s conversation, please take a moment to subscribe and share this interview with your friends.

And don’t forget to leave us a rating and review.

Next week we bring you interviews with Dr. Chris Wright and Dr. Ivor Poobalan who discuss the theological impetus the movement has had on global mission.

Here is a clip from an interview with Dr. Chris Wright

Clip from Chris Wright

Chris Wright

One of my reflections is that I do, from time to time, just get a bit weary of being asked the same question that was being asked back in the 1970s and 80s, you know, ‘Which do you think is more important evangelism or social action?’ I think that’s like asking which is more important, breathing or drinking?

You know, I mean, you have to do both, or you’ll die. I mean, they are different. They’re distinct. But they’re part of an integrated, holistic system, namely the human body. And in a complex system, you’ve got multiple realities, but they’re all essential. They should all be held together. You don’t ask which is more important, except in some circumstances.

So, for example, if somebody’s bleeding on the street because they’ve been knocked down, then you’ve got to stop their bleeding. Bleeding is more important at that moment than giving them a cup of tea. So. But as John Stott says, in most circumstances, this distinction between evangelism is conceptual. These things are different, but they all have to be held together.

Jason W

Well, I hope that you enjoyed that clip from Dr. Chris Wright. It was truly an enlightening interview that I’m certain that you will enjoy.

If you haven’t yet, please don’t forget to rate and review this podcast. The more reviews we get, the more likely others are to find it.

Until next time.

We’d love your feedback to help us to improve this podcast. Thank you!

Guests in This Episode

Doug Birdsall

Honorary Co-Chair

S. Douglas (Doug) Birdsall served as executive chairman of the Lausanne Movement from 2004 to 2013. He led the movement through a process of global revitalization, culminating in the convening of the Third Lausanne Congress on World Evangelization: Cape Town 2010. A graduate of Wheaton College, Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, Harvard University, and the Oxford Centre for Mission Studies, UK, he is president of The Civilitas Group.

Ramez Atallah

Ramez Atallah served as the IFES Regional Secretary for the Middle East (1980-1990). He then took on the role of General Secretary of the Bible Society of Egypt. In addition to these responsibilities, Ramez played a significant part in the Lausanne Movement. He was the Program Chair for the Third Lausanne Congress on World Evangelization in Cape Town in 2010 and later served as a Deputy Chairman for the Movement from 2010 to 2015.

Subscribe to the Podcast

Get the latest content from Lausanne delivered straight to your inbox