The Story of a Victim

He arrived in Glasgow via London on the overnight bus. Over a hot cup of coffee in our city centre drop-in, and with the aid of a volunteer who could speak his language, he was able to tell us some of his story.[1]

Victims of exploitation and trafficking are to be found all over the world.

He had left Africa for Europe in order to escape terrorism and warfare there and had managed to find his way to Belgium. He had hoped that he would be able to claim asylum, acculturate, and make a life for himself in Europe. But like so many others he found himself vulnerable to exploitation. He was delighted when a Belgian farmer offered him employment, and he worked hard for him for many weeks. He was given very basic accommodation along with some others, and was provided with food. At first it seemed to be a good arrangement, but it soon became obvious that the farmer had no intention of paying him. When he asked for his wages he was given short shrift.

And so he decided to leave, but where could he go? He opted for the UK and arrived in Glasgow, knowing no one, and speaking no English. After several nights sleeping rough, he was exhausted, hungry, and bewildered.

Victims of exploitation and trafficking are to be found all over the world. Many have been exploited while escaping religious or ethnic persecution, or, like this man (I will call him Thierry), fleeing war. And their numbers are set to increase. As I write, over three million people have had to leave Ukraine as a result of the invasion of their country by Russian forces. In their displacement and desperation, they are highly vulnerable to exploitation by human traffickers who know whom to target. Already it is reported that many children have gone missing on the Ukrainian-Polish border.[2]

At our drop-in centre, it is our privilege to be able to work with victims of exploitation, to learn something of their stories, and help them as best we can. In Thierry’s case, we were able to help him find the right support, and I am happy to report that life has turned around for him. He has started the long journey of learning how to live with the trauma of his past and in hope for a more stable life.[3]

I say it is our privilege, and indeed it is. But we are very much aware that we are scratching the surface of what is a tragic situation for millions of people throughout the world. We are also very aware that we are dealing with the damage done by those who exploit others—serving people whose lives have been wrecked by criminals who see them only as commodities.

It is the responsibility of Christians not only to work with victims but to help prevent such suffering in the first place.

Our ministry, like so many others, works with the victims of exploitation and human trafficking. We are generously supported financially by churches and by many volunteers who give up their time to listen and walk alongside people like Thierry. We would much rather, however, that such exploitation did not happen at all. And we believe that it is the responsibility of Christians not only to work with victims but to help prevent such suffering in the first place.

But how can individual Christians and church communities do this? For many, it might feel like a problem that is ‘out there’, well divorced from our everyday experience. We know there are people like Thierry, and would love to prevent further suffering, but what can we do about such a huge problem which affects millions throughout the world?

Learning from History

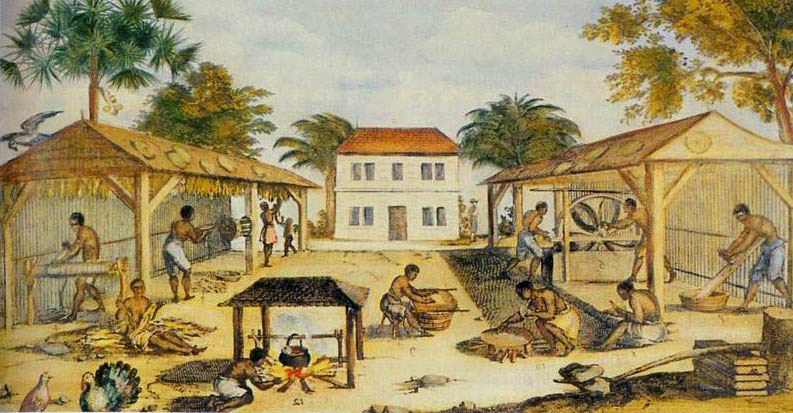

We can learn a great deal from the Quakers of Antebellum America, who did so much to speak out against the injustice of slavery.[4] In their time, slavery was the norm, and very few people had ever questioned it. Most Christians took it for granted that they should be able to own slaves, and found support for their view in Scripture. The Quakers, however, began to challenge this—how could slave ownership be compatible with the biblical principles of freedom and equality? They began to stand up against the values and norms of the prevailing culture, both within the church and in society as a whole.

“Slaves working in 17th-century Virginia,”

Central for them was the so-called ‘Golden Rule’: ‘So in everything, do to others what you would have them do to you, for this sums up the Law and the Prophets” (Matt 7:12). They realised that they themselves would not want to be enslaved, and so they could not inflict this on others. Inevitably, their stance drew criticism and hostility, in particular from Christians who found support for slave-holding in the biblical writings.[5] Nevertheless, they stood up against the prevailing culture, both in society and amongst Christians, and played a large, crucial part in the story of abolition.

The maxim ‘Do unto others what you would have them do to you’, can be the impetus to do something about modern-day slavery.

For us, too, the maxim ‘Do unto others what you would have them do to you’, can be the impetus to do something about modern-day slavery. Perhaps the most obvious way is to support and be involved in services which enable people like Thierry to build up new lives for themselves. We can bring God’s love into the lives of those who have experienced years of exploitation, and of being treated as commodities. But there is also much that we can do to help prevent exploitation and enslavement.[6] Like the Quakers, we can join the prophetic tradition of seeking justice and mercy, and speaking truth to power. Like the Quakers, we can campaign against the injustice that is human trafficking, and become involved in awareness-raising. We can speak out against the commodification of human beings, and lobby people in power. We can boycott those companies whose goods are produced by people who are being exploited.

But it is not enough just to identify and treat the signs and symptoms of any disease. It is important to tackle the causes. And the causes of human trafficking are many and complex—lack of opportunity, capitalism, and inequality (racial, social, religious, and gender), amongst others.[7] These are political matters, of course, and there are many Christians who are involved in trying to change things at this level. But very often, the root cause lies much deeper. People find themselves exploited because of human failings—greed and lust for power over others. And here Christians do have something to say, for the prophetic tradition which makes itself heard throughout our canon of Scripture, and in which Jesus himself stands, warns us against these very things.

Examining Ourselves

If our message is to be credible, we must first, surely, examine ourselves. First, we must ask ourselves about our attitude towards money and possessions. Are we driven by love of money or love of God? Jesus is clear—you cannot serve both God and mammon (Matt 6:24). For Christians living in materialistic cultures, this can be a particularly hard issue to face.

But there is much more to the causes of human exploitation than economic matters. The exploitation of others is also facilitated by assumptions about people. It makes it so much easier to exploit someone if you believe that they are inferior to you because of race, religion, social status, or gender. Much commercial sexual exploitation of women comes about because they are seen merely as objects, for example, and many people are seen as commodities because they are considered to come from an inferior race or religion.[8]

It makes it so much easier to exploit someone if you believe that they are inferior to you because of race, religion, social status, or gender.

So, we must examine ourselves about these too. Attitudes towards race, religion, social status, and gender are very much culture-bound, and throughout the history of Christianity, Christians have wrestled with when we should adhere to the norms of the prevailing culture and when we should challenge them. Sometimes this has caused great problems within the church itself, as in the case of slavery.

The difficulty is also reflected in Scripture, not only in the Old Testament prophets and in Jesus’ stance against the religious leaders of the day, but also in the early church itself as, for example, in the letter to the Galatians. In Galatia, the church was being assailed with demands from people that they should conform to certain religious practices amid assertions that those who did not conform were to be considered religiously inferior. Paul argued strongly against this and insisted that this was an attempt to place the Galatians under a ‘yoke of slavery’ (Gal 5:1). He objected to the idea that believers from pagan, rather than Jewish, backgrounds were inferior Christians.

Moreover, he widened the parameters of his argument and declared that in baptism all become equal: ‘There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female’ (Gal 3:28). These famous words do not mean that Paul is saying that racial, social, and gender differences be disregarded altogether. What he is saying is that the cultural and religious presuppositions which can govern our thinking, and whose influence we may not necessarily be aware of, can come to dominate our communities to the extent that our ability to love one another can become compromised (Gal 5:6).

Responding to the Challenge

Paul’s words challenge us to reflect on our own attitudes with regard to race, gender, and social status in our churches. Do we really see each other as equals? How far do we prioritise our cultural and religious norms at the expense of the freedom to love and serve each other which Christ’s new creation brings?

It takes courage, as the Quakers well knew, to challenge accepted norms, even and perhaps especially within the church.

These can be difficult questions within churches, but we ignore them at our peril—for if our communities do not model what we want to advocate for the rest of the world, our prophetic voice in wider society can only be weakened. It is vital that we Christians prayerfully and with humility are willing to examine our attitudes with regard to money and possessions, social status, and differences of gender, ethnicity, and religion (including our theological differences) if we are to be credible witnesses for social justice in our world. At the very least, we must be willing to acknowledge our own weaknesses and prejudices and try to understand where our cultures have compromised our ability to love our neighbour, even within our own communities.

It is a privilege to be part of Thierry’s life and to see hope restored to him. But our responsibilities do not stop there. We also have an obligation to tackle the causes of human trafficking by being a prophetic voice against the values and norms of the world in which slavery is able to flourish. However, if our voice is to be effective, we must first be willing to examine our own values and ask—how far do our communities live up to the standards which we ourselves advocate? It takes courage, as the Quakers well knew, to challenge accepted norms, even and perhaps especially within the church. But if we are to have a prophetic voice in this world, and help prevent the enslavement and exploitation of people like Thierry, we must first examine ourselves.[9]

Endnotes

- The author serves as chaplain at Glasgow City Mission, Glasgow, Scotland.

- Sue Mitchell, ‘Ukraine: Thousands of vulnerable children unaccounted for,’ BBC News, March 11, 2022, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-60692442.

- On the medical and psychological help needs of trafficked persons see Hemmings, S., Jakobowitz, S., Abas, M., et al. ‘Responding to the health needs of survivors of human trafficking: a systematic review,’ BMC Health Services Research 16 No 1. 2016, doi:10.1186/s12913-016-1538-8.

- On the Quakers and abolitionism, see Brycchan Carey and Geoffrey Plank (eds) Quakers and Abolition (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2018).

- See further, Marion L.S. Carson, Human Trafficking the Bible and the Church: An Interdisciplinary Study (Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2016).

- See Kevin Bales, Ending Slavery: How We Free Today’s Slaves (Berkeley: University of California, 2007).

- Annalisa V. Enrile, Ending Human Trafficking and Modern Day Slavery: Freedom’s Journey (Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications 2018, 51-70).

- On the various forms of contemporary slavery see the Trafficking in Persons Report which is produced yearly by the United States State Department.

- Editor’s Note: See article by Abraham (Abey) George entitled ‘Human Trafficking and the Response of the Global Church,’ in the January 2014 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis, https://lausanne.org/content/lga/2014-01/human-trafficking-and-the-response-of-the-global-church.

Photo credits

Photo by Hermes Rivera on Unsplash

1670 virginia tobacco slaves. “Slaves working in 17th-century Virginia,” by an unknown artist, 1670. This work is public domain.

Photo by Hermes Rivera on Unsplash