Introduction

In the past, mission hospitals run by foreign missionaries were the most common setting for healthcare missions. These efforts to improve the health of people in very challenging circumstances preceded any effort on the part of the non-religious world by nearly 100 years (not taking into account the health and healing ministry of the church from the time of Jesus onward!). However, the world has changed and is changing rapidly. This is evident in terms of global health but also, more importantly, in the realm of missions overall, where the centre of Christianity has also shifted. Therefore, we should ask: how should mission-minded Christian health professionals and missional organizations respond? To answer that question, we need to have a deeper understanding of the state of health and healthcare in the world.

Healthcare Missions in the 21st Century

Some may believe that healthcare missions means Christians using healthcare simply as a platform to evangelize. However, many of us believe that it [healthcare missions]is about Christians using our God-given skills as health professionals in an area of need, providing high-quality health services, while demonstrating the love, compassion, grace, mercy, and healing of the triune living God, and where appropriate, explicitly sharing the salvific message of this God. In short, it is a complex endeavour in a complex world, and it is not to be taken lightly!

In the twenty-first century, a healthcare missionary may not necessarily work in a mission hospital, but in a secular job, often in areas that are less sophisticated than where they are originally from. Any hierarchy of ‘real missionaries’ or ‘only tent-makers’ are unhelpful.

Understanding the Complexity of the Challenge

The health of the world has improved greatly in recent decades, but the longstanding issues still remain, and new issues have emerged.

Infectious diseases, including diarrhoea and pneumonia,[1] HIV,[2] malaria,[3] and tuberculosis[4] still kill millions of people needlessly, especially the most vulnerable; much progress has been made but a huge unfinished task remains. Neglected tropical diseases (including leprosy, leishmaniasis, schistosomiasis, onchocerciasis, lymphatic filariasis)[5] will continue to cause suffering, disability, and premature death until concerted efforts are made to eradicate them.

However, many of us believe that it [healthcare missions]is about Christians using our God-given skills as health professionals in an area of need, providing high-quality health services, while demonstrating the love, compassion, grace, mercy, and healing of the triune living God, and where appropriate, explicitly sharing the salvific message of this God.

Non-infectious diseases, such as diabetes, high blood pressure, heart attacks, strokes, chronic lung disease (often caused by smoking) disproportionately kill people in lower-income countries.[6] Road injuries are the most common cause of disability and death in people aged 10 to 49 years globally, and disproportionately affect lower-income countries.[7] The rates of cancer are rising in lower-income countries, but treatment options have often not proportionally increased.[8] Also, it is increasingly understood that many cancers and other non-infectious diseases can be prevented by lifestyle changes, but prevention is the hardest for those with fewest material resources.

Poor mental health,[9] disabilities,[10] and terminal illnesses[11] are amongst the most challenging areas of healthcare that require more services and more community awareness in almost every country, but especially in lower-income countries.

Other than diseases, there are the social,[12] political,[13] and commercial[14] determinants of health that should be considered and addressed, while war,[15] environmental pollution,[16] and climate change,[17] have detrimental health impacts that require innovative solutions. Demographic changes, including migration,[18] urbanization,[19] and ageing populations,[20] also affect the health needs of communities. The emigration of health professionals from lower to higher income countries[21] causes weak health systems to become less able to meet health needs.

Governments, health systems, and educational institutions are responding to these challenges: eight hundred new medical schools started worldwide between 2000 and 2014,[22] governments in low- and middle-income countries continue to increase their investments in their health systems.[23] Billions of dollars of official development assistance (foreign aid) are given by individual governments to others governments,[24] in addition to billions of dollars of donations from large private philanthropic organizations that fund healthcare and health research.

In short, there continue to be many complex problems in the world, but many resources have already been directed to address them, though more are always needed.

Developing Strong Health Systems

Weak health systems result in people unable to receive the healthcare they need, and its causes may include weak leadership or governance, insufficient financing, inadequate service provision, a poorly-trained health workforce, weak supply-chains, and ineffective health information systems.[25] Therefore, to provide better healthcare to a community, there is seldom one simple solution, but rather, strengthening several of these areas in the existing health system may be necessary.

Strengthening a health system from the inside by working in partnership with the existing people and services, could include a mentoring approach to strengthen leadership, providing training to improve the skills of staff, providing expertise to upgrade a health information system, rather than bringing an external team in to set up an alternative system that only benefits a few. In some situations, setting up a new health facility to fill in the gaps in the system (eg a new mission clinic) may be appropriate to consider. But those who wish to do so must allocate sufficient expertise and resources to all areas of the mini-health system they are setting up, and ensure it is well-connected to the greater health system locally.

Improving the Quality of Healthcare

Research shows that more people in the world die of poor quality healthcare than from the lack of access to health services.[26] In the past, the goal of missionaries was often to provide healthcare where there was none, often making-do; in other words, focus was on access, rather than quality. Nowadays, improving the quality of healthcare is a goal even in lower-income countries, and secular organizations are focusing on quality of healthcare in resource-limited settings, therefore Christians should be embarrassed not to do likewise. To put it bluntly, if we are going to provide healthcare in the name of Jesus, we must do it well!

‘traditional’ model of missions is no longer relevant in most places. Rather, health professionals who are committed followers of Christ, well-equipped with advanced professional skills, are needed to solve complex problems, often in secular specialist organizations, to bring God’s healing, in the name of Christ.

High-quality healthcare requires many resources, but it can be achieved in countries with relatively low-income levels.[27] This may include training individual health professionals to be competent, ensuring appropriate resources and motivation for health professionals to consistently perform well, and good leadership. Clinical guidelines enable quality and ought to be followed, even in resource-limited settings. Good research, which might not be complex, that objectively determines the best solutions for problems, can also be an important part of bringing high-quality healthcare. A doctor alone can seldom achieve good outcomes alone without the input of other health professionals, administrators, data managers and analysts, educators, communication experts, plus a strong community and family that provide psycho-social-spiritual support. Thus, healthcare mission could legitimately include those diverse roles.

Christians on the Cutting-Edge of Global Health?

‘Global health’ has become a popular term in the last 10-20 years, but Christian missionaries have been on the forefront of global health for centuries, and arguably, Christian healthcare missions could be considered the forerunner of the current global health movement. However, Christians are now often no longer on the cutting-edge of global health, but secular organizations and individuals are. While many Christian missionaries and Christian healthcare organizations around the world continue to do much good work in healthcare in difficult circumstances, there are still many who are following traditional models which were perhaps more appropriate a few decades ago, and some may have limited impact. At the same time, there are many secular global health practitioners who are very innovative and do high-impact work; the majority are probably doing God’s work, though often not in God’s name. Therefore, Christians would do well to learn from those best practices when working under formal mission organizations, or else not be embarrassed about joining the efforts of effective secular organizations.

Modern Healthcare Missions

In some places, a mission hospital may still be appropriate, with long-term foreign missionaries providing leadership and clinical care. However, in many places, Christians would do well to go beyond that model. The following are some of the features of contemporary healthcare missions that are important:[28]

- Any programme must be effective and sustainable, empowering the community, rather than by a charity approach that causes dependency.

- Working within complex systems, and not expecting that one intervention will produce immediate positive results.

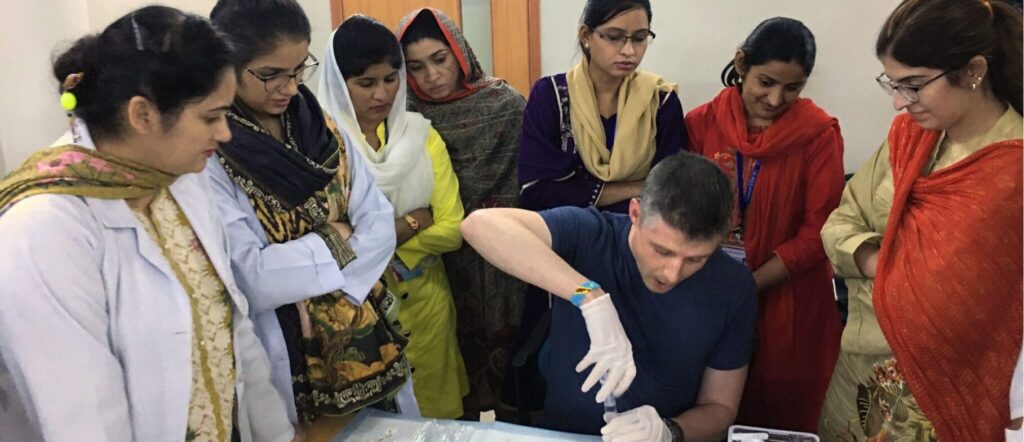

- Sending experts, rather than enthusiastic-but-inexperienced people.

- Quality (provide gold-standard care), not just access(anything is better than nothing), with best practices in assuring quality (eg monitoring and evaluation).

- Supportive (eg teaching, mentoring, advising) rather than direct clinical care.

- Strengthening skills required for health systems (eg research, leadership, data management).

- Partnering with or working within secular organizations, including governments.

- Individual missionaries and their families may not necessarily be in the mission field in the long term (eg 1-3 year terms, and not a lifetime), but if they are, they should not lose relevance in the home country (eg regular visits to the home country, maintaining specialist licensing/registration in the home country).

- Underserved areas in high-income countries may almost be as needy as lower-income countries.

- Adequately equipping Christians to serve as missionaries effectively in secular organizations without neglecting their theological knowledge and spiritual practice, and having an incarnational approach as a missionary (eg learning the local language, living as a local, showing care and concern for their neighbours’ psycho-socio-spiritual as well as physical well-being).

- Explicitly preaching the Christian message may not be possible (eg being expelled from a country, or going against a secular employer’s code of conduct), but living out the gospel to earn the right to be heard[29] and likely to be done in a private setting.

Conclusion

Many young Christians dream of following in the footsteps of missionary doctors who spent their lives working in mission hospitals in faraway countries. However, in the 21st century, the world is far more complex than it was even a few decades ago, and that ‘traditional’ model of missions is no longer relevant in most places. Rather, health professionals who are committed followers of Christ, well-equipped with advanced professional skills, are needed to solve complex problems, often in secular specialist organizations, to bring God’s healing, in the name of Christ.[30]

Endnotes

- Perin J, Mulick A, Yeung D, Villavicencio F, Lopez G, Strong KL, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000-19: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. 2022;6(2):106-15. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00311-4

- ‘The path that ends AIDS: UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2023’, UNAIDS, https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2023/global-aids-update-2023.

- ‘World Malaria Report 2022’, World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2022.

- ‘Global tuberculosis report 2022’, World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2022.

- ‘Global report on neglected tropical diseases 2023’, World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240067295.

- Bennett JE, Stevens GA, Mathers CD, Bonita R, Rehm J, Kruk ME, et al., ‘NCD Countdown 2030: worldwide trends in non-communicable disease mortality and progress towards Sustainable Development Goal target 3.4’, The Lancet, 22 September 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31992-5.

- Vos T, Lim SS, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi M, Abbasifard M, et al., ‘Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019’, The Lancet, 17 October 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9.

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A, ‘Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries’, CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 6 April 2020, https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3322/caac.21492.

- Rehm J, Shield KD, ‘Global Burden of Disease and the Impact of Mental and Addictive Disorders’, Current Psychiatry Reports, 7 February 2019, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-0997-0.

- ‘World report on disability, 14 December 2011’, World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564182

- Knaul FM, Farmer PE, Krakauer EL, De Lima L, Bhadelia A, Jiang Kwete X, et al., ‘Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief—an imperative of universal health coverage: the Lancet Commission report’, The Lancet, 12 October 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32513-8.

- Marmot M, ‘Social determinants of health inequalities’, The Lancet, 19 March 2005, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(05)71146-6.

- Mackenbach JP, ‘Political determinants of health’, European Journal of Public Health, 23 January 2014, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckt183.

- Gilmore AB, Fabbri A, Baum F, Bertscher A, Bondy K, Chang H-J, et al., ‘Defining and conceptualising the commercial determinants of health’, The Lancet, 23 March 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00013-2.

- Garry S and Checchi F, ‘Armed conflict and public health: into the 21st century’, Journal of Public Health, September 2020, https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdz095.

- Fuller R, Landrigan PJ, Balakrishnan K, Bathan G, Bose-O’Reilly S, Brauer M, et al., ‘Pollution and health: a progress update’, The Lancet Planetary Health, 17 May 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00090-0.

- ‘COP26 special report on climate change and health: the health argument for climate action, 11 October 2021’, World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240036727

- Abubakar I, Aldridge RW, Devakumar D, Orcutt M, Burns R, Barreto ML, et al., ‘The UCL-Lancet Commission on Migration and Health: the health of a world on the move’, The Lancet, 5 December 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32114-7.

- Khor N, Arimah B, Otieno RO, Oostrum Mv, Mutinda M, Martins JO, et al., ‘World Cities Report 2022: Envisaging the Future of Cities’, UNHABITAT, https://www.unhabitat.org/wcr/.

- ‘World Population Ageing 2019: Highlights’, United Nations, December 2019, https://www.un-ilibrary.org/content/books/9789210045537.

- Dohlman L, DiMeglio M, Hajj J, Laudanski K, ‘Global Brain Drain: How Can the Maslow Theory of Motivation Improve Our Understanding of Physician Migration?’ International Journal of Enviromental Research and Public Health, April 2, 2019, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16071182.

- Rigby PG and Gururaja RP, ‘World medical schools: The sum also rises’, JRSM Open, 5 June 2017, https://doi.org/10.1177/2054270417698631.

- ‘Global spending on health: a world in transition.’, World Health Organization, 12 December 2019,https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HIS-HGF-HFWorkingPaper-19.4.

- Knox D, ‘Aid spent on health: ODA, data on donors, sectors, recipients’, Development Initiatives, 24 July 2020, https://www.devinit.org/resources/aid-spent-health-oda-data-donors-sectors-recipients/.

- ‘Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies’, World Health Organization, 2010, https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/service-availability-and-readinessassessment%28sara%29/related-links-%28sara%29/who_mbhss_2010_cover_toc_web.pdf.

- Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, Jordan K, Leslie HH, Roder-DeWan S, et al., ‘High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: time for a revolution’, The Lancet Global Health, 5 September 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30386-3.

- Balabanova D, Mills A, Conteh L, Akkazieva B, Banteyerga H, Dash U, et al., ‘Good Health at Low Cost 25 years on: lessons for the future of health systems strengthening’, The Lancet, 8 April 2013, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62000-5.

- Nungarai N, Paul M, John N, Goh W-L, ‘Considering Medical Missions in all its Different Forms: A Viewpoint from the Asia-Pacific Region’, Christian Journal for Global Health, 8(1), 2021:42-52, https://doi.org/10.15566/cjgh.v8i1.523. Cattermole, ‘Global health: A new paradigm for medical mission?’ Missiology:An International Review, November 24, 2020.

- Bill Peel and Jerry White, ‘Workplace Evangelism for the 99 Percent’, Lausanne Movement, 12 July 2023, https://lausanne.org/about/blog/workplace-evangelism-for-the-99-percent.

- Editor’s Note: See article entitled, ‘Faith, Health, and Collaborative Love: Pandemic Partnership For Health Professionals And The Church’ by Ted Lankester in the January 2021 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis, https://lausanne.org/content/lga/2021-01/faith-health-and-collaborative-love.

Photo Credits

Header Image by [World Bank Photo Collection] from Flickr

Image 1 by [World Bank Photo Collection] from Flickr

Image 2 by [World Bank Photo Collection] from Flickr

Image 3 by [MedGlobal Org] from Flickr

Image 4 by [MedGlobal Org] from Flickr

Image 5 by [World Bank Photo Collection] from Flickr

Image 6 by [World Bank Photo Collection] from Flickr