While under lock-down in Asia, far from our family, but in a country we love, my wife and I are pondering questions around staying or leaving in the light of the worldwide COVID-19 crisis. We are not alone. Never in history has this question come to the minds of so many cross-cultural workers at the same time.

Green Leaf in Drought by Isobel Kuhn

We are noticing that the rhetoric is a lot about risk. Is COVID-19, and the likelihood of the appearance of other coronaviruses, an opportunity to rethink our missiology with regard to risk? In this article, we use the concepts of ‘polarity management’ and ‘mental models’ to explore if our present missiology of risk still holds true.

Not new

My wife and I are presently reading a book by Isobel Kuhn, Green Leaf in Drought,[1] in which she describes the situation where the missionaries of the China Inland Mission found themselves halfway through the previous century. Foreigners were so hated by the regime that anyone who had contact with them risked their own safety. The mission leaders decided to call home all their 600-plus missionaries to protect the emerging and still fragile Chinese church. It is worth noting that in the last couple of years this situation where foreigners had to leave has been repeated even though the context was slightly different.

Many of us may have had to make ‘leave-or-stay’ decisions in the light of sickness, children’s needs, war, unrest, or for other reasons. It is just that now, with the COVID-19 crisis, the scope is unprecedented.

Many of us may have had to make ‘leave-or-stay’ decisions in the light of sickness, children’s needs, war, unrest, or for other reasons. It is just that now, with the COVID-19 crisis, the scope is unprecedented.

Duty of care

In recent decades, more attention has been given to care for cross-cultural workers. The concept of ‘member care’ gained traction in the mission world in the 1990s.[2] This was triggered by research that showed that a significant number of overseas workers and their children had developed mental health problems. Books such as Honourably Wounded,[3] first published in 1987, made a big impact. Since then, all sizable mission organizations, particularly in the West, have added a department to look after the care of the staff on the field. Such care and avoiding unnecessary harm have become a high value in mission.

Honourably Wounded by Marjory F. Foyle

Incarnational mission

There is no doubt that mission work includes taking risks. Going overseas usually increases your risk of being in a car accident, catching infectious diseases, going through significant cultural stress, and being in other risky situations. Jesus Christ himself did just that: he came out from the very safe place of heaven to the discomfort of the human world to be ridiculed, persecuted, and eventually killed. Most of the apostles were martyred, and the Scriptures are full of exhortations about living in the midst of hardship. Over the centuries, many missionaries died on the mission field, and, even though nowadays medical care and other measures make the risks less dramatic, it is still the case that cross-cultural mission involves taking risks and can therefore result in physical, emotional, or mental harm.

Mission of God

Major shifts have taken place in the thinking about mission over the last decades, and the evangelical movement is slowly catching up. The ‘from the West to the rest’[4] mentality caused a kind of patriotism that could create the caricature image of a hero from afar saving the local heathen.[5] Mission has now become much more ‘from everywhere to everyone’,[6] which is resulting in the rethinking of the role of the expat. The expat nowadays is usually part of a team or national network and might be reporting to a national leader. For the national teammates, the issues of risk, such as becoming infected, are very real too, but, for them, there is often no choice about whether to stay or leave. Choices about leaving then become a team issue. We are all together in the mission of God, not in a mission of the West.

Biblical principles

As already mentioned, the greatest example in the Bible of someone leaving a place of safety to stay in a place of risk is of course Jesus himself. There are also plenty of Bible verses that remind us that we should not be unduly concerned about our own safety nor think too much about ourselves but focus only on the Lord. For example, Acts 20:24: ‘But I do not account my life of any value nor as precious to myself, if only I may finish my course and the ministry that I received from the Lord Jesus, to testify to the gospel of the grace of God’ (ESV). Self-sacrifice is a core value for every Christian, and particularly for those sent to reach the unreached.

But there are also biblical references that call for caution. There were times when Jesus avoided harm. For example, Jesus walked through the crowd and escaped (Luke 4:30), and the disciples were instructed to move on to another town if they were not received well (Matthew 10:14). Several passages emphasize that we are all part of one body (1 Corinthians 12), and this includes our spouses, our children, and our teammates. Paul, in 1 Timothy 5:8, compares neglecting our families’ needs with unbelief. In a broader sense, Jesus himself said, ‘By this all people will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another’ (John 13:35). This verse highlights that this care for each other is part of our testimony to outsiders.

Polarity Management by Barry Johnson

Polarity

As we explore the staying-or-leaving question, we need to keep the seemingly opposing values behind the biblical principles in a healthy tension. To do that, we can use the Polarity Management model developed by Johnson.[7] The model helps to manage the values tension in such a way that potentially negative outcomes are reduced and potentially positive outcomes are pursued while keeping both values alive.[8]

The issue of vulnerability or risk seems to be at the centre of most conversations. On the one hand, we and our sending constituency want to be responsible and protect ourselves and our team-mates from becoming sick or hurt in a situation where there are limited care and medical facilities. On the other hand, our passion for the people around us and our loyalty to the local partners press us to be present in vulnerable situations, especially when life is tough. Even if there is not much we can do to help, at least we can suffer together with the people. We find ourselves wanting to find the ‘sweet spot’ in the continuum between risk-avoidance and risk-taking.

Exploring responses

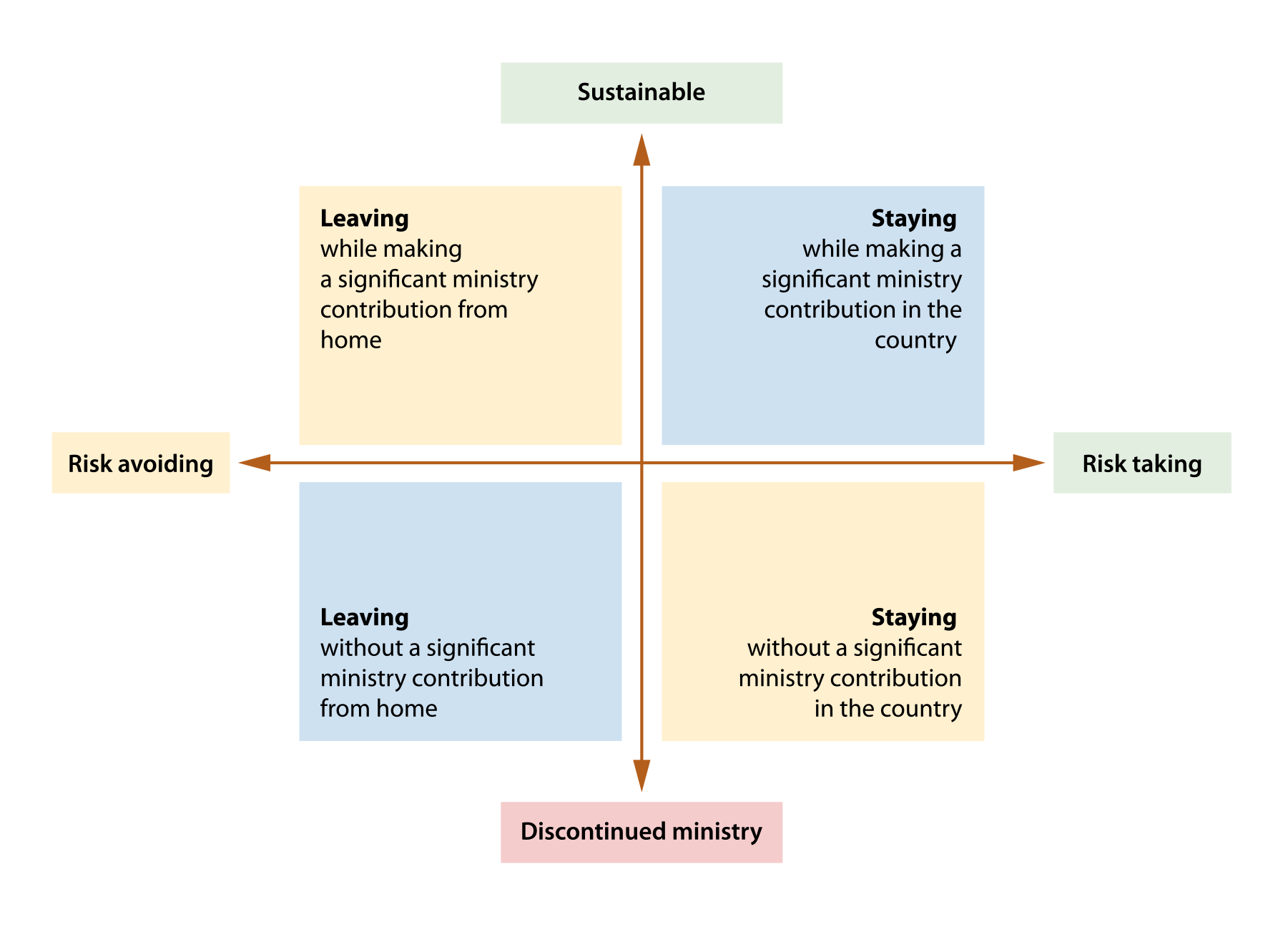

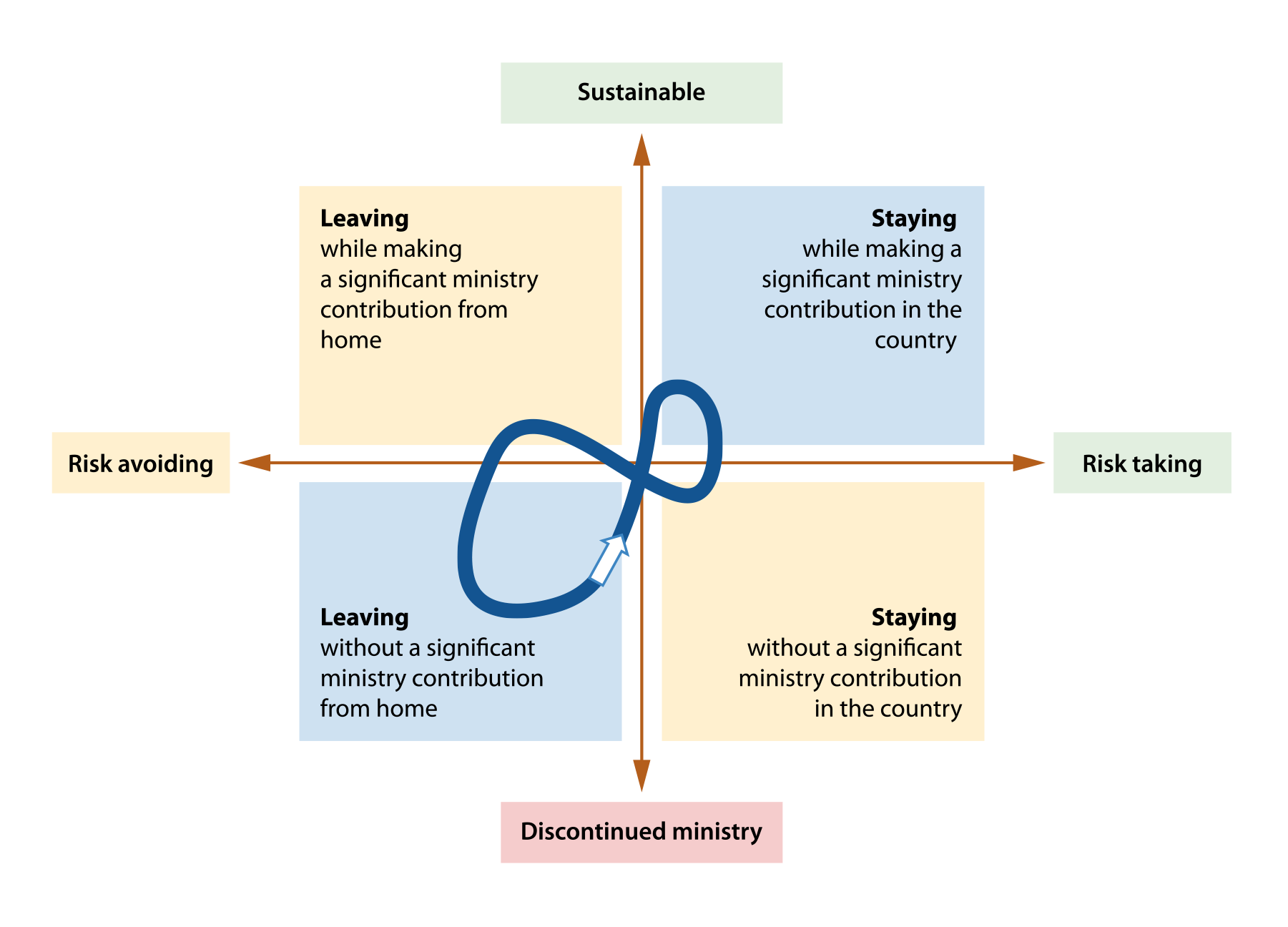

As we explore the issues related to risk, we also find ourselves wondering what will happen to the ministry entrusted to us if we leave or if we stay. We basically see four options that we could consider:

- Leaving, with the expectation that relationships can be maintained and engagement with the ministry work can be done from our home country

- Leaving, while accepting that our relationships and ministry engagement will stop or be significantly reduced

- Staying, in the hope that the relationships and ministry engagement can be continued

- Staying, while accepting that restrictions may make it difficult to remain in relationships and engage with the ministry.

Placing these options in the Polarity Management model looks like this:

Mental model or missiology

In order to explore these options, it would be helpful to introduce the concept of mental models: ‘Mental models are deeply ingrained assumptions, generalizations, or even pictures or images that influence how we understand the world and how we take action.’[9] In other words, what is the missiology on which we base our decisions with regard to risk?

Discovering our mental models is not as easy as it seems. We are usually not aware of our deeper-level values, until they are violated.

Discovering our mental models is not as easy as it seems. We are usually not aware of our deeper-level values, until they are violated. For the mission’s home office, there is often such a sense of responsibility and loving care for staff members that the avoidance of risk becomes a natural part of the rhetoric in the prayers and policies for the mission workers. Other high values, such as children’s education, care for elderly parents, and long-term engagements in the ministry can move our missiology more towards risk avoidance. There might be an unwritten assumption that dying on the field should be avoided at all costs. But is that biblical and has that been discussed with the sending church, the organization, and the team?

There can also be cultural considerations. For some cultures, risk-taking might be very acceptable but it might be unthinkable to miss the funeral of a father or close relative. This value might be high enough to cause the worker to be based in the home country for a while, when the possibility of travel is questionable.

Lack of balance

Questions have been raised whether the increased value for care has created mental models, of which we are not aware, that drive our discussions to prioritize one quadrant of the Polarity Management model over others. Missiologist Christopher Ducker suggests that the concept of vulnerability should be brought back into our missiology: ‘I propose that vulnerability should be a defining characteristic of mission in the twenty-first century. By vulnerability I mean exposing oneself (normally deliberately) to risk and uncertainty, including the possibility of hardship, injury, and attack.’[10] This fits well with the statement of the great cross-cultural missionary, the apostle Paul: ‘For Christ’s sake, I delight in weaknesses, in insults, in hardships, in persecutions, in difficulties. For when I am weak, then I am strong’ (2 Corinthians 12:10).

In the diagram below, the conversations taking place are depicted by the blue line. The diagram assumes that those conversations are ongoing as the COVID-19 crisis continues to unfold, hence the line is a closed loop. The fact that the loop is dipping deeper into the bottom left quadrant depicts that the conversations are hovering more around avoiding risk and are not keeping the sustainability of the ministry and relationships in mind. If that happens, we know that the missiology behind our conversations has gotten out of balance.

Likewise, if the conversation is predominantly about sacrificing and suffering, it would be equally out of balance. In that case the loop would dip deeper into the bottom right quadrant, particularly if the possibility that one might become a liability to the vulnerable community is ignored.

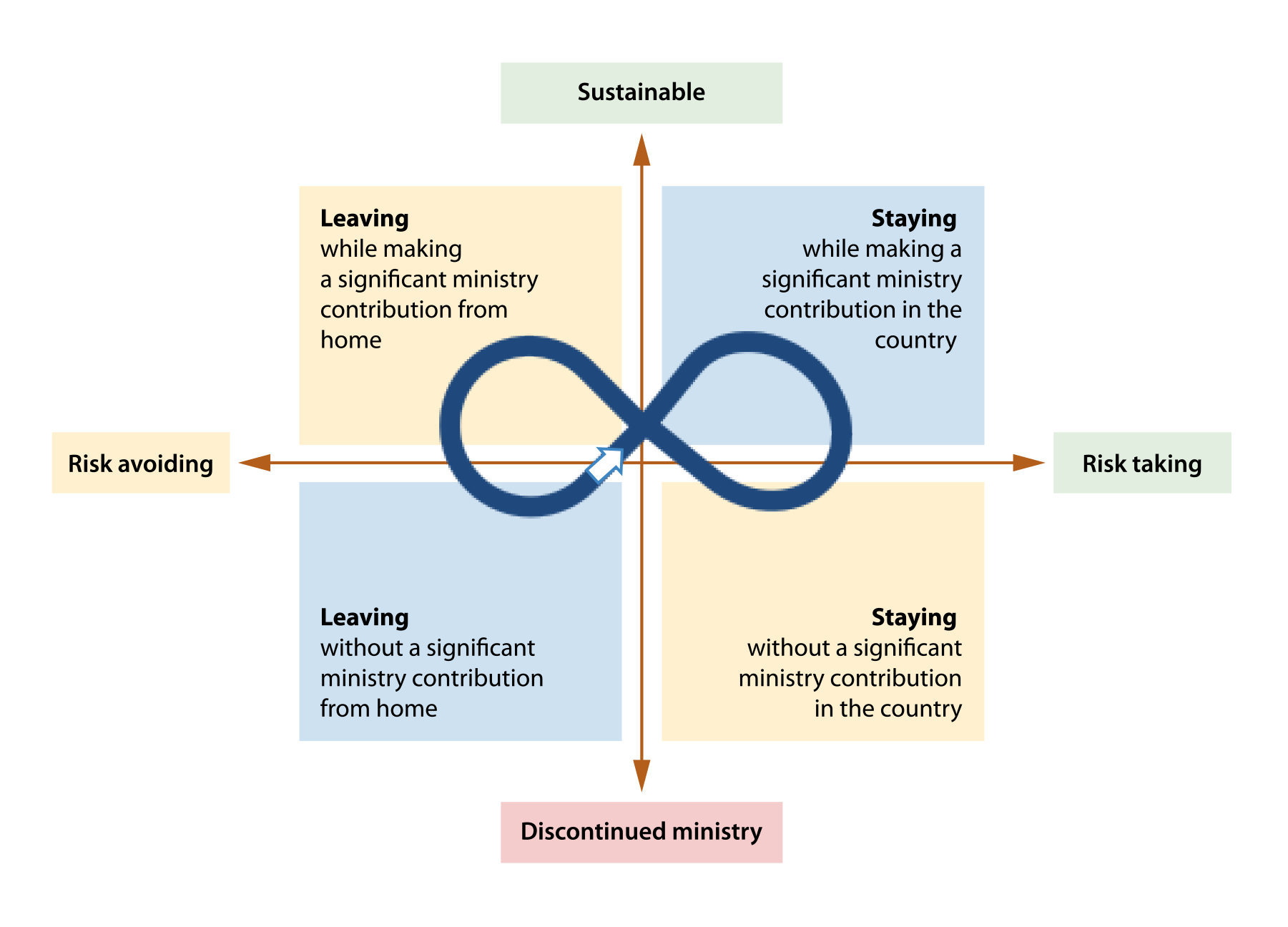

Healthy conversations

Assuming that our missiology has a healthy balance between the care for ourselves and the zeal and passion for the ministry and people, we would envision conversations being focused on the impact the decision would have on long-term ministry. This might well mean that leaving is the best option, but the main reason should not be to avoid risk to the individual, but because it would be best for the long-term sustainability of the ministry and relationships. The blue line in the diagram below depicts the place where we feel the conversations should take place.

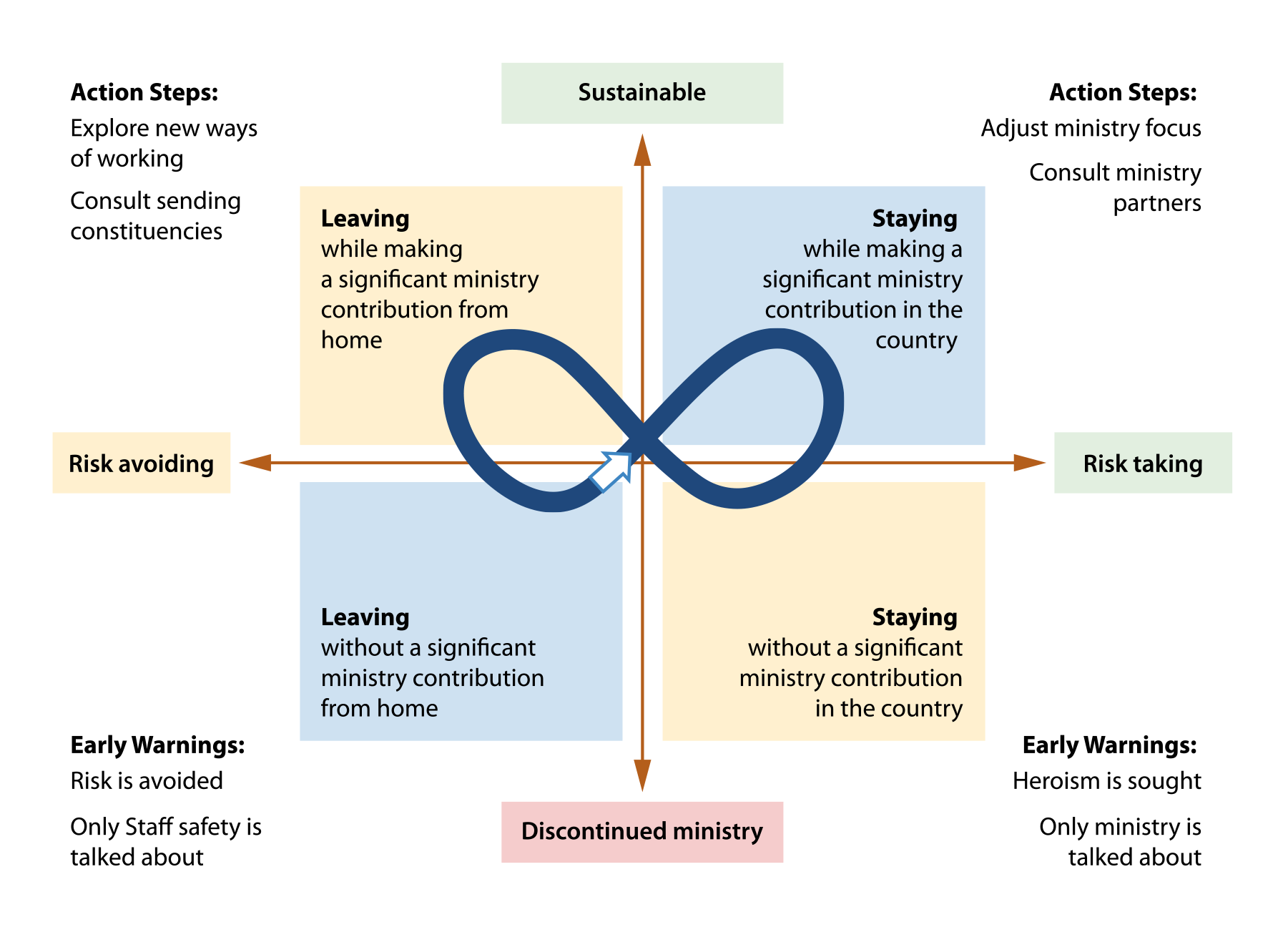

Staying on track

As the development of the COVID-19 crisis is quite unpredictable, conversations can easily slip back to focussing on risks and fears. It is therefore good to identify signs of ‘early warnings’—indicators that tell us that we are sinking into one of the lower quadrants of the Polarity Management model. This could be when, for example, we find ourselves either talking only about our own well-being or catch ourselves using heroic language about staying.

On the positive side, we should focus on ‘Action Steps’—interventions through which we gain or maintain the positive results from our focusing on this polarity. We are maintaining the right focus when, for example, we are spending our energy exploring new ways of working, expanding or adjusting the ministry focus, and consulting with the right stakeholders. This makes the full polarity management diagram look like this:

Rethinking risk[11]

As my wife and I prayed about the question of staying or leaving, we discovered that there are even deeper issues related to this. We are now asking ourselves questions such as:

- What is my missiology of risk? What are my deeper values and beliefs around risk-taking?

- Do I really love the people I live among, even when this means exposing myself to high risks?

- Am I falling into the trap of wanting to be a hero, even if, with staying, I only become a liability?

- Whose decision is it whether I leave or stay? What weight should be given to the voices of the ministry partners, the sending church, the leadership of the organisation, and the workers?

- Is it time to consider new ways of working in which the ministry is less dependent on expat presence?

The COVID-19 crisis might reset the mental models we presently use for overseas missions with regard to risk. It might move us away from the tendency to avoid risk, toward embracing risk in a responsible way. It might also expedite the rethinking that has been taking place in the last few decades about the role of outsiders; the trend to place the work from the start into the hands of brothers and sisters from the country itself. The late great missiologist David Bosch said about the vulnerability of mission: ‘… Christianity is “unique” because of the cross of Jesus Christ. But then the cross must be seen for what it is: not a sign of strength, but as proof of weakness and vulnerability. The cross confronts us not with the power of God, but with God’s weakness.’[12]

Endnotes

- Isobel Kuhn, Green Leaf in Drought (Singapore: Harold Shaw Publications, 1994).

- Kelly O’Donnell, ‘The Missional Heart of Member Care’, International Bulletin of Mission Research (April 2015), https://doi.org/10.1177/239693931503900210.

- Marjory F. Foyle, Honourably Wounded: Stress Among Christian Workers, Kindle Edition (London: Monarch Books, 2009).

- Niall Ferguson, Civilization: The West and the Rest (Great Britain: Penguin Books, 2012).

- Jean Johnson, We Are Not the Hero. (Sisters, OR: Deep River Books LLC, 2012).

- Samuel Escobar, The New Global Mission: The Gospel from Everywhere to Everyone (Downers Grove, Ill: IVP Academic, 2003).

- Barry Johnson, Polarity Management: Identifying and Managing Unsolvable Problems (Amherst, MA: H R D Press, 2014).

- The Polarity Management model is not the best tool for what Johnson calls an ‘either-or’ issue (see chapter 6), but in the context of this article I still found it a helpful model.

- Peter M. Senge, The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of the Learning Organization (New York: Currency, 2006).

- Christopher Ducker, ‘Missio Dei (the Mission of God),’ Yumpu.Com 2008.https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/54406328/missio-dei-the-mission-of-god-theduckersorg.

- Editor’s note: See article by Sue Arnold, entitled, ‘The Risk of Reaching the Unreached,’ in September 2019 issue of Lausanne Global Analaysis, https://lausanne.org/content/lga/2019-09/risk-reaching-unreached.

- David J. Bosch, ‘The Vulnerability of Mission,’ Baptist Quarterly 34, no 8 (1992): 351–63, https://doi.org/10.1080/0005576X.1992.11751898.