Brother Ashok[1] leads a discipleship centre in South Asia. He shared his plans for expansion with a potential resourcing partner who helped him develop a project with clear goals, strategies, budgets, and timeframes.

‘On the one hand, I really liked it—it helped me to think things through,’ says Ashok. ‘On the other hand, it raised questions such as: Is all this planning replacing my faith in God? Is the paperwork coming in the way of relationships? Does this approach fit with my culture or is it Western?’

In recent decades, the missions movement has seen a trend towards ‘projectisation’—the use of systematic processes to solve problems, improve efficiency, and support growth, with measurable outcomes and goals. In other words, the overlap of business best practises with the world of missions. I have felt a personal need to reflect on this from a biblical perspective and to see how the opportunities can be capitalised on and the pitfalls mitigated.

As Jesus initiated his worldwide ministry, he operated quite differently from current project management best practices

Values in Tension

As Jesus initiated his worldwide ministry, he operated quite differently from current project management best practices. Instead of recruiting reputable people, he built a team composed of outcasts. Instead of having prudent time management skills, he crammed his entire ministry into the last three years of his life. Instead of communicating clear goals and plans, he referred vaguely to the ‘kingdom of God’. Instead of creating a solid budget, he relied on unpredictable hospitality. Elsewhere in the Bible, people are urged to trust in God, rather than rely on ‘chariots and horses’ (Ps 20:7). David Bosch attributes features such as reason, causality, progress, and the belief that all problems should be solvable to the Enlightenment. One could argue that the thinking behind projectisation is more a fruit of the Enlightenment than of the Bible.[2]

However, as the missiologist Andrew Walls points out, simply dismissing the present philanthropic culture would not be biblical.[3] Walls’ Pilgrim Principle affirms that, as Christians, our values are often in tension with the world around us. This makes us different but should not make us walk away. His Indigenizing Principle recognizes that God has placed us within cultures in which we should actively participate. Walls encourages us to embrace both principles and keep them in tension.

Nehemiah seemed able to keep these principles in tension. He presented a ‘project proposal’ to the Persian king before heading off to Jerusalem (Neh 2:7‒9), worked systematically, and was goal oriented. Still, throughout, his trust in the Lord was evident as he executed his plans and dealt with obstacles. Other heroes led equally focused and progressive projects—Noah: ‘Project Flood Rescue’, Moses: ‘Project Let My People Go’, and Paul: ‘Project Reach the Gentiles’—while also living out the principle of Proverbs 3:5, ‘Trust in the Lord with all your heart, and do not lean on your own understanding.’

Samuel had difficulty managing this tension when Israel demanded a king. He wanted them to trust in the Lord rather than in the then-fashionable management model of monarchy. However, the Lord allowed kingship (Deuteronomy 17:14-20), and the value tensions were managed by setting boundaries and keeping the kings in line through prophets.

Does a project approach create a mindset in which numbers are more important than people and quality?

Weaknesses and Strengths

Anybody working in a project-centred way can tell you the downsides—excessive paperwork, reduced flexibility, and endless meetings. In addition, at a deeper level, questions emerge: Does a project approach create a mindset in which numbers are more important than people and quality?[4] Is this requirement to projectise a new form of colonialism?[5] Does it enforce the Enlightenment thinking that, if we do things right, results will follow? In other words, are missions projects doing what many of the Old Testament kings did—consuming a lot of resources and making us trust in ‘our own understanding’ (Prov 3:5) rather than in God?

However, there are some significant positives. All too often we see literacy efforts that only produce a handful of readers, Bible translations that drag on for decades, and church plants that remain forever dependent on their planters. There are plenty of positive examples where planning, strategizing, and accountability have greatly increased the impact of such missions work[6]. Moreover, when ministry is done in a project format, more funders are willing to donate larger amounts. Just as the good kings were a blessing to Israel, well-planned and well-managed projects with kingdom-focused goals can be a blessing to the ministry.

Factors and Forces

In recent decades, forces have moved towards more projectisation in the charity sector. The global growth of terrorist networks and money-laundering make Western governments nervous about money leaving the country, while governments on the receiving end are increasingly wary of civil society organisations meddling in their internal affairs. International bank transfers are therefore heavily scrutinized and transfers have to be traceable through project plans and budgets. Besides, due to globalisation and an increased distrust in institutions, resourcing partners want to know how their money is being used.

In the Western evangelical missions world, there is a general belief that ‘the task’ of the Great Commission can be accomplished, and soon. This started with the optimism of the 1910 Edinburgh Conference to ‘save the heathen’ and was followed by the Lausanne 1974 call to reach the ‘unreached people groups’ and Cape Town 2010’s ‘aim to eradicate Bible poverty’ (CTC II-D-1). Western evangelical activism is creating a demand for tangible data, results, and accountability.

Every 21st-century organisation—in missions or otherwise—is expected to care for its staff, use its money well, and have a professional board. This has led to further professionalisation of missions organisations with projectisation as a critical component.

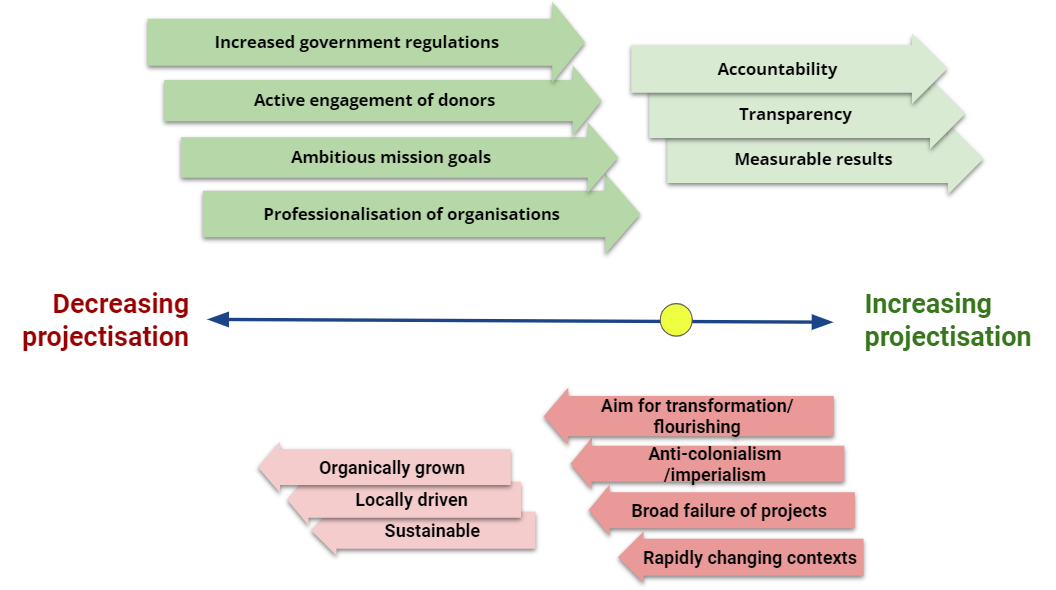

The diagram below shows how these trends have fuelled the drive towards projectisation in charities in general, and specifically in missions.

Force-Field Analysis of Projectisation: The present forces towards projectisation are stronger than the forces away from it.

At the same time, there are specific forces working against projectisation. It is recognised that projects tend to focus on measurable results, losing sight of deeper impact. Already in 1991, Samuel Escobar wrote that ‘managerial missiology fails to appreciate those aspects of missionary work that cannot be measured or reduced to figures. In the same way it has given prominence to that which can be reduced to a statistical chart.’[7] The 2021 Micah Network conference had as its theme Kushamiri (Kiswahili for ‘flourish’)—an aim that goes much deeper than that which can be described through measurable goals and time-bound project activities.

The reality of our highly unstable world, with natural disasters, civil unrest, persecution, pandemics, etc. on the rise, makes it next to impossible to make plans and stick to them.

Besides, neocolonialist behaviour—the tendency of Western organisations to determine and control what is ‘good’ for other nations—is increasingly unwelcome in many nations. There are repeated calls to reverse that trend and instead work together as equals.[8] Projectisation is often considered a tool from the West to control the rest and can be subject to suspicion. Furthermore, in the work of development, it is recognized that the success rate of projects is actually quite low.[9] Lastly, the reality of our highly unstable world, with natural disasters, civil unrest, persecution, pandemics, etc. on the rise, makes it next to impossible to make plans and stick to them. The context is changing all the time and working in a project mode is not the best way to deal with such constant fluidity.

Despite the arguments and voices against aspects of projectisation, a broadly-accepted alternative has not yet been identified, so the trend towards projectisation continues.

Mitigating Negative Impacts

Given the inevitable pervasive influence of projectisation, I searched for some practical ways to mitigate potential negative impacts. Here are a few examples I have noticed:

![]() Participatory development:[10] A local missions organisation finds out from communities what is needed and what resources are available. This makes the project more community-focused and less directed by the priorities of the outsiders.

Participatory development:[10] A local missions organisation finds out from communities what is needed and what resources are available. This makes the project more community-focused and less directed by the priorities of the outsiders.

![]() National representatives: An international resourcing partner employs people from the country to represent them. This makes the project partnership more culturally sensitive and less neocolonial.

National representatives: An international resourcing partner employs people from the country to represent them. This makes the project partnership more culturally sensitive and less neocolonial.

![]() Oral reporting: At reporting time, a missions leader talks with the project managers. He then fills out the forms, which they review and approve. This makes the reporting process more culturally appropriate and reduces paperwork.

Oral reporting: At reporting time, a missions leader talks with the project managers. He then fills out the forms, which they review and approve. This makes the reporting process more culturally appropriate and reduces paperwork.

![]() ‘Divine opportunities’: A planning consultant creates space for unexpected opportunities to the Results-Based Management (RBM) model. This reduces the risk of rigidity.

‘Divine opportunities’: A planning consultant creates space for unexpected opportunities to the Results-Based Management (RBM) model. This reduces the risk of rigidity.

![]() Discretionary funds: One resourcing agency allows a 10 percent margin to allow for handling unexpected opportunities with minimal paperwork. This provides flexibility and reduces administration.

Discretionary funds: One resourcing agency allows a 10 percent margin to allow for handling unexpected opportunities with minimal paperwork. This provides flexibility and reduces administration.

Prophetic Questions

Just as Israel quickly forgot all the warnings Samuel gave when appointing their first king, we too often forget the pitfalls of working in project mode. We need a prophetic voice to keep us alert. Here are some ‘prophetic questions’ for project staff and stakeholders to discuss and pray about on a regular basis:

Content:

‘Lord, is the project (still) in line with what you want? Are we spending our energy and time on things important to you?’

Implementation:

‘Lord, are we representing you well in the way we engage with communities, deal with our staff, handle money, talk with partners?”

Relationships

‘Lord, are we inviting you into all our relationships? Are we loving, transparent, and open with all stakeholders?’

Project dependencies:

‘Lord, can we make changes when we feel led by you to change, or have we become too dependent on others to decide for us?’

Project measures:

‘Lord, what counts the most with you? What priorities should we focus on when we track and report on progress?’

If there are issues around these questions, conversations with the right stakeholders will need to follow. This will need prayer and sometimes a ‘prophet Nathan’ to speak up!

Reflection

In appointing a king, Israel used a risky but often effective management model to survive in the promised land. Under good kings, Israel thrived. Likewise, brother Ashok switched to a project approach in order to build his ministry, and it really helped to expand and manage his ministry. But even the best kings of Israel were reminded by prophets of their dependence on the Lord. In the same way, we and Ashok need to regularly pause to listen to a ‘prophetic voice’ to ensure that our projects do not overtake our ministry.

Endnotes

- Based on a real situation, but with a fictitious name and painted in with details from other situations.

- David Bosch, Transforming Mission: Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission (Maryknoll, N.Y: Orbis Books, 1991), 268 ff.

- Andrew Walls, The Missionary Movement in Christian History: Studies in the Transmission of Faith, first edition (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books & Edinburgh: T&T Clark), 1996.

- Scott Bessenecker talks critically about the ‘businessfication of the faith’ in missions in his book, Overturning Tables: Freeing Missions from the Christian-Industrial Complex (IVP Books: 2014), 98.

- Neocolonialism can be defined as the control of less-developed countries by developed countries through indirect means, https://www.britannica.com/topic/neocolonialism. See also: Robert Young, Post Colonialism: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003).

- See for example: Peter White and Benjamin O. Acheampong, ‘Planning and Management in the Missional Agenda of the 21st Century Church: A Study of Lighthouse Chapel International’, Verbum et Ecclesia 38, no. 1 (2017).

- Samuel Escobar, ‘A Movement Divided: Three Approaches to World Evangelization Stand in Tension with One Another’, Transformation: An International Journal of Holistic Mission Studies 8, no. 4 (October 1991):7–13, https://doi.org/10.1177/026537889100800409.

- See for example, Joerg Rieger, ‘Theology and Mission between Neocolonialism and Postcolonialism’, Critical Readings in the History of Christian Mission (April 2021): 531–554, https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004399594_009.

- Lawrence Boakye and Li Liu, ‘With the Projectisation of the World, the Time Is Right to Unravel Why International Development Project (IDP) Failure Is Prevalent’, Universal Journal of Management 4, no. 3:79.

- A good starting point is the Wikipedia page on participatory development.