The growing zeal of China’s urban churches to send missionaries overseas appears to be on a collision course with President Xi Jinping’s drive to control religion in China and also his signature One Belt One Road Initiative to extend trade and political influence through Buddhist and Muslim nations west of China. This collision made international news when two missionaries from China were kidnapped and killed in Pakistan by ISIS in 2017. The incident strained relations between the two nations at the highest levels. It also led China to issue a statement condemning ‘illicit’ missionary activity and to increase surveillance to identify and remove Chinese ‘tentmaker’ missionaries operating overseas.

It also led China to issue a statement condemning ‘illicit’ missionary activity and to increase surveillance to identify and remove Chinese ‘tentmaker’ missionaries operating overseas.

Growing economy, churches, and missions

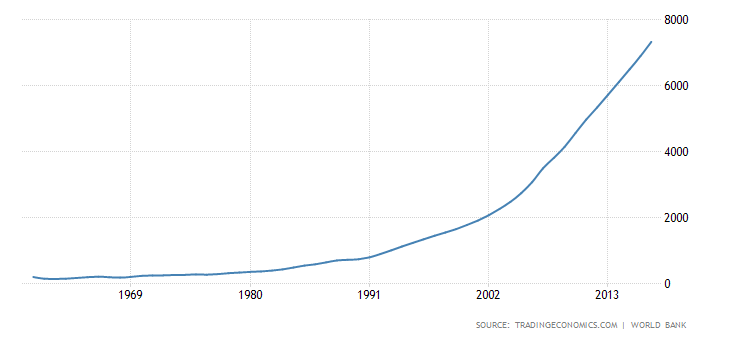

Both Xi’s One Belt One Road initiative and recent mission activity by China’s large urban churches have been made possible by China’s economic rise globally. Gone is the international isolation and extreme poverty that bedevilled China through much of the 20th century. Instead international connections and trade have become major engines of China’s economy that have led to a surge of Chinese investment throughout the world in order to gain both political leverage and economic advantage.

The period from 1962 to 2017 has seen China’s GDP soar.

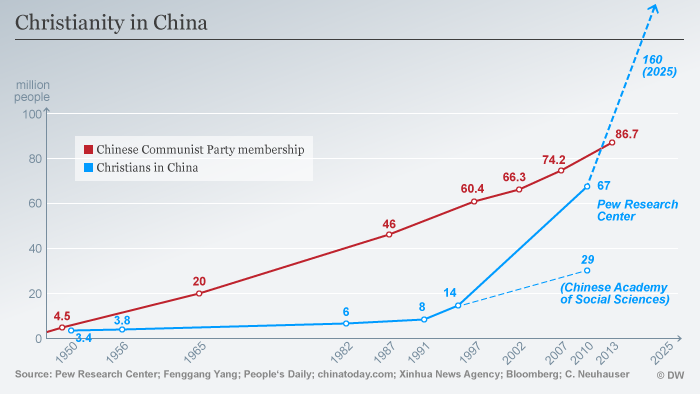

Even so, this meteoric rise of China’s GDP rise lags behind the growth of Christianity in China during the same period.

Given the explosive growth of both China’s international economy and its urban churches, it is not surprising that they influence the missionary movement taking root in China’s churches:

- Freer labour markets with their huge appetite for skilled labour, especially in coastal regions, have given rise to an upwardly mobile and internationally connected and educated bourgeoisie keen to take advantage of the need for skilled and technologically savvy labour necessary to drive China’s transformed manufacturing, financial, international trade, and engineering sectors.

- Urban churches are now filled with congregants whose standard of living, levels of education, and ways of life are now common in China’s urban centres.

- Thus, like their fellow upwardly mobile citizens, urban Chinese Christians often are found in professions that require travel both in and out of China as part of China’s expansive international business ventures.

This provides new opportunities for mission. As one urban church leader notes:

Urban emergent churches have higher education and more cross-cultural experience. In the past, rural churches boasted of great faith in mission ministry; today, the urban emergent church has human talent and financial resources.[1]

Financial fortunes, divine providence, and the missionary movement

Many Chinese Christians believe the rise in China’s economic fortunes, as well as their own, is God’s divine providence enabling Chinese Christians to join in the Great Commission. As one Chinese pastor notes:

For those who live in mainland China, we have experienced a change of income. Compared to our income twenty years ago, our income has increased . . . more than two times. With the housing price soaring . . . over the past ten years, many people get rich. But from the perspective of the history of salvation, the development of economy is preparation for mission.

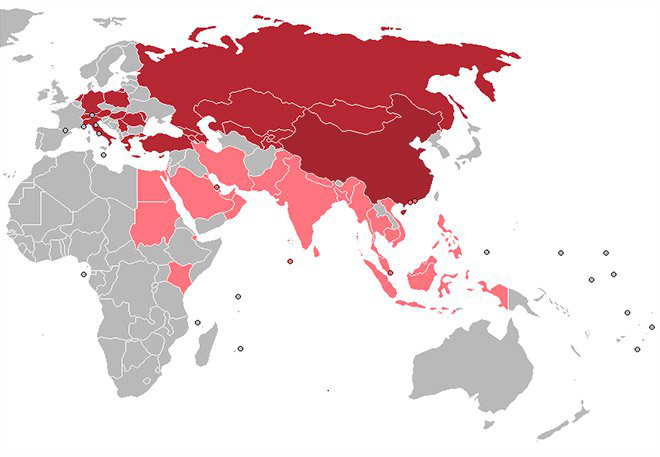

Thus, just as early Western missionaries used business and employment to make inroads into China, Chinese church leaders see opportunity in Xi’s One Belt One Road Initiative to send ‘tentmaker’ missionaries as managers, engineers, translators, and skilled labourers along the trajectory of the ancient Silk Road through the Muslim nations to the West.

China’s One Belt One Road

Dark Red: Mainland China, Red: One belt economies; Pink: One road economies (Pittman, 2019)

Modern Chinese missionaries

Thus, even as The One Belt Road Initiative recruits engineers, architects, and planners, it brings onboard missionaries who are young, educated, and from the rising middle classes and sent by urban Chinese churches.

Paradoxically, Xi’s One Belt Road Initiative dovetails with the Chinese Christian narrative of a Back to Jerusalem missionary movement[2] that arose out of visions and prophecy that Chinese Christians would complete the circle of global mission through Central Asia and the Middle East to Jerusalem.[3] Accordingly, Xi and his initiative are unwitting agents of God’s divine plan to reach the nations for Christ. As one urban church leader noted:

…the One Belt One Road initiative is similar to church of China’s vision, which is going west with the gospel. We see this as a calling for this time period, God is doing His work through the people who are in charge and so the church of China should go to the West at this time.

Deepening tension between church and state

This recent missionary activity has only deepened hostility between the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and Christians in China. From the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the CCP has feared the connection between missions and Chinese Christians. It has viewed churches as channels of destabilization fundamentally opposed to the ideology of Marxism, Maoist ideology, and CCP rule. The rise of urban Chinese church missions has only deepened the angst of the CCP.

This recent missionary activity has only deepened hostility between the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and Christians in China.

Quite often it is Overseas Chinese Christians’ mission organizations which financially support mainland Chinese churches in their mission work; it thus appears to the CCP to represent foreign meddling. This has led to new moves by the Chinese government to sever all international mission ties between mainland Chinese Christians and Overseas Chinese mission agencies.

Further, Chinese missionary activity, especially in Muslim nations west of China, represents another problem for the CCP. The government fears that reaction to Chinese missionaries coming from China could threaten economic and political ties and even stir Islamist reactions against China and its Chinese workers in these countries. This is all the more sensitive given their crackdown on Muslims in China. So far Muslim nations and leaders have looked the other way, but, should China be seen by Islamist groups as a vehicle for Christian missions, it could lead to a religious and political backlash against the One Belt One Road Initiative.

Thus, Chinese churches’ sense of divine missionary calling and opportunity appears on a collision course with powerful forces within the state and the CCP. The former sees the hand of God opening up new mission fields that fulfil their divine mission destiny, while the latter sees the growth and influence of Christianity and mission as an existential economic, political and ideological threat.

What happens next?

Xi’s recent campaign to ‘sweep away dark evil’ has now been directed toward ‘evil forces’ hidden within religion, and particularly ‘foreign’ religions such as Christianity and Islam, in China. The current rhetoric of government campaigns calls for the eradication of house churches, a move that has already begun in Beijing. Should the government employ the tactics used against the Falungong or the Uyghur Muslims of Xinjiang, it could result in the mass incarceration of Christians in China, which would significantly stymie mission activity both in and outside China.

From the founding of the People’s Republic, the security apparatus of the state has played a ‘cat and mouse’ game with unregistered churches and church leaders to monitor their activities and rein in their growth and influence. The state has spent huge sums to install a massive virtual security ‘panopticon’ in China’s cities that ties the latest in Artificial Intelligence (AI) to monitoring equipment, much of it employed to control religious activity:[4]

Security cameras linked to AI are now required in all churches.

Facial recognition software tracks individuals by ubiquitous CCTV cameras in all venues, public, or private.

This allows state security bureaus to monitor an individual’s movements and note where and with whom they associate.

State harvesting of biometric data, smartphone scanners, voice analysis, and satellite-tracking systems for vehicles allows for constant surveillance round the clock.

The introduction of 5G technology will only enhance this ability to monitor all aspects of lived reality, not only in China but around the globe.

Arrest and re-education of ‘religious extremists’ based on monitoring data even before they commit any crime is now policy in China.[5]

In the past, unregistered church members were able to disappear into the massive urbanscape of China’s cities, but now this ability to ‘hide’ is increasingly constrained both in and outside China.

As of February 1, new legal measures designed to rein in all religious activity have come into force:

The measures comprise six chapters and 41 articles addressing the organization, functions, offices, supervision, projects and economic administration of all religious activity in China, including formation, gatherings, and daily activity. Each must now be approved by the government’s Religious Affairs Department.

Article 34 requires that all proposed activity in churches must be submitted in advance to authorities and carried out only if approved. ‘Without the approval of the Religious Affairs Department of the people’s government, or registration with the Civil Affairs Department of the people’s government, no activities can be carried out in the name of religious groups.’[6]

If Article 34 is effectively enforced, non-registered churches and their mission activity will be eliminated.

China’s mission ‘new normal’

This latest crackdown on religion is the ‘new normal’ for registered and unregistered churches, and they are adjusting to it as best they can.[7] Large worship services are breaking up into smaller less visible clandestine house group meetings.

This has also forced Chinese churches to rethink their mission strategies and activity as they seek to survive in an era of official hostility. As one pastor of a large unregistered church noted: ‘if we are reduced to just being able to pray for the nations, we will continue with our mission vision’.

For churches and mission institutions beyond China, it is a time for prayer and discernment, as well as adaptation to a very different political context in China.

Thus, the vision remains, even as the circumstances adjust mission activity on the ground.

How long this will affect the burgeoning mission movement in China remains unclear. The events in China are a reminder that, as mission work takes hold in nations beyond Western Christendom, the dynamics of mission and its relationship to the secular and religious powers are uncertain and often face severe headwinds as they strive to move forward.

Certainly, for senior leaders of Chinese churches and mission institutions these crackdowns on Christianity and churches are nothing new. From the founding of the PRC, Chinese Christians have weathered periodic persecution only to emerge stronger. For churches and mission institutions beyond China, it is a time for prayer and discernment, as well as adaptation to a very different political context in China. How this ultimately affects and shapes the Chinese mission movement, only time will tell.

Endnotes

- This and subsequent quotations from urban Chinese pastors are part of an extensive research project by David Ro in 2016–2018 as part of his doctoral research at the Oxford Centre for Mission Studies. The study goes into far greater depth than the current article and will address similar themes of China missions. To protect the identity of the interviewees, their names are not mentioned. On the whole, the pastors interviewed are pastors of large urban unregistered churches in various parts of China.

- Editor’s Note: See article by David Ro, entitled, ‘The Rising Missions Movement in China’, in May 2015 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis, https://lausanne.org/content/lga/2015-05/the-rising-missions-movement-in-china-the-worlds-new-number-1-economy-and-how-to-support-it

- K.-K. Chan, ‘Mission Movement of the Christian Community in Mainland China: the Back to Jersualem Movement’, in W. Ma & K. Ross, eds. Edinburgh 2010 Volume II (2010).

- Editor’s Note: See article by Thomas Harvey, entitled, ‘The Sinicization of Religion in China’, in September 2019 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis, https://lausanne.org/content/lga/2019-09/sinicization-religion-china.

- BBC News, ‘Inside China’s ‘Thought transformation’ Camps’ https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/world-asia-china-48667221/inside-china-s-thought-transformation-camps. 17 June 2019. Accessed 17 January 2020.

- ‘China tightens its grip on religion: New measures aim to ensure religious groups implement total submission to the Chinese Communist Party’, UCA News. 3 January 2020. https://www.ucanews.org/news/china-tightens-its-grip-on-religion/86909. Accessed 19 01 2020.

- Editor’s Note: See article by Joanne Pittman, entitled, ‘The New Normal for Christianity in China’, in May 2019 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis, https://lausanne.org/content/lga/2019-05/the-new-normal-for-christianity-in-china.

Photo credits

Image from ‘Belt and Road Initiative‘ by SKas (CC BY 4.0). Description: Roundtable meeting of leaders at Belt and Road international forum