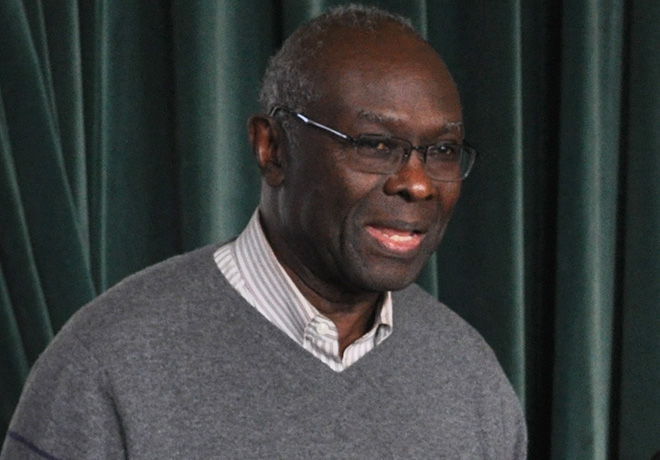

On 6 January 2019, theological academia around the world was rocked by the sudden and unexpected passing of Professor Lamin Sanneh. Born in an ancient African royal family in 1942, in Gambia, a small country in the westernmost part of Africa, Sanneh grew up as a Muslim and converted to Christianity in his late teenage years. Throughout his life, he held an impressive portfolio of academic achievements and appointments. At the time of his passing, he was the D. Willis James Professor of Missions and World Christianity at Yale Divinity School, a position he had held since 1989. He led numerous other initiatives, one being a flagship project on Religious Freedom and Society in Africa. The Sanneh Institute at the University of Ghana in Accra was founded in 2018 and named in his honor. It seeks to resource academic institutions in the advanced study of religion through curricular design, faculty development and research.[1]

Sanneh also had an impressive record of publications as author, editor, or co-editor of books, monographs, and peer-reviewed journal articles.

Reassessing the impact of missionaries during the colonial era

Translating the Message: The Missionary Impact on Culture by Lamin Sanneh

One of his landmark writings, published by Orbis Books in the American Society of Missiology Series is entitled, Translating the Message: The Missionary Impact on Culture.[2] The book went through 13 printings. In it and related essays, Sanneh dissociates Christian mission from the ideological claim that missionaries were imperial agents, and mission work was an extension of the colonial empire. Much of the colonized world had achieved independence in the late 1950s and the 1960s. In the immediate post-colonial backlash, it was argued that mission work was the willing instrument of colonial administrators and settlers. Missionaries had been set loose to introduce a false piety, weaken resistance, and prepare natives to acquiesce to colonial control. As agents of western cultural alienation, they enabled settlers to annex African land with ease.

By the late 1960s through the 1980s when Sanneh was coming up in the academic ranks, Western liberal academia had joined this vitriolic censure of missionary work. Among mainline church circles, the shadow of this censure exacted a heavy price of guilt on mission agencies. Educational institutions, hospitals, and development initiatives that had been founded by missionaries were facing lethargic malaise in their diverse social roles. A caustic attitude in African churches that were founded by missionaries hampered religious enthusiasm and conversion. Sanneh adds a biographical note to the dilemma when he tells how both a Methodist and a Catholic missionary were reluctant to baptize him when he chose to convert from his Muslim faith into Christianity. All that negative characterization of Christian mission was not only paralyzing the spread of the gospel in Africa but also dismissing the real significance of hundreds of years of Christian mission across Africa and elsewhere.

Sanneh turns the narrative of missionary complicity in the colonial project on its head.

This postcolonial backlash is vital to understanding Sanneh’s prodigious writing and distinguished career as a historian, scholar of World Christianity, and advocate of interreligious dialogue. Sanneh turns the narrative of missionary complicity in the colonial project on its head. He does not deny that some missionaries were problematic in their individual attitudes towards local cultures. What he does is to show that there is a lot more to the story, and that has to do with the nature of the gospel itself. He assesses the 2000-year historical transmission process, and the local contexts in which missions were conducted and concludes that vernacular translation is the primary, critical, leavening, or catalytic action in the spread of the Christian faith. The Christian message can be expressed in any language and interpreted into any culture. Therefore, translatability is the key to the spread of Christianity to new cultures across time, as has happened across Africa, Asia, and Latin America over the last 200 years.

In a 1987 essay entitled ‘Christian Mission and the Pluralist Milieu: The African Experience’,[3] Sanneh observes that missionaries ‘went out with all sorts of motives, some of them unwholesome’, yet, ‘what stands out is the emphasis missionaries gave to translating scripture into vernacular languages’. They confidently adopted local languages, a new and bold move for the era, and in so doing they were affirming local cultures as vessels to carry the gospel of Christ. They wrote grammars, translated the Bible, started schools, taught people to read and write, collected and preserved local wisdom of stories, proverbs, and axioms. They adopted the pre-existing names for God and reinterpreted traditional cosmology in light of Christian faith.

The self-interested colonial settlers were never going to undertake such a project. In fact, in the environment in which missionaries were operating, colonial overlords rated indigenous cultures extremely low on the Darwinian evolutionary scale, and whatever they could not use in the service of colonial interests, they were prepared to destroy.

Sanneh systematically examines Christian history to demonstrate that the pattern observed in missionary work is in fact the same process of transmission of Christianity across time.

Far from destroying indigenous cultures, missionary work catalyzed the preservation and stimulation of these cultures. Missionaries helped to preserve languages that were threatened by rising lingua-francas. Their grammars, dictionaries, primers, readers, and systematic compilations of proverbs, stories, and customs also furnished the scientific community with documentation for modern study of cultures. In turn, as converts came to have alternative readings of the translated scriptures, particularly of the Old Testament, and to discover the alignment of the Old Testament world with the local cultural customs, communities all over Africa used the gains of mission to offset or fight back against colonial domination; in this, mission work itself had the impact of equipping the nationalists themselves with a language of resistance.

Sanneh systematically examines Christian history to demonstrate that the pattern observed in missionary work is in fact the same process of transmission of Christianity across time. In ‘Disciples of All Nations: Pillars of World Christianity’,[4] he explores the missionary nature of the Christian faith: the freedom of early Christians to embrace other languages such as Greek, Latin, and Coptic, and so enabled the critical moment of transmission of the gospel from its Jewish beginnings, setting it free to go into all the world. The willingness of early Christians to identify with the Gentile movement freed the disciples from obligations to maintain a geographic center at Jerusalem. Every single phase of geographical and cross-cultural expansion of Christianity reflects similar patterns. Christianity does not primarily depend on a fixed language or culture and has no exclusive geographical frontier; it thus comes as a liberating message to every person and culture.

Pioneering studies in World Christianity

Whose Religion is Christianity: The Gospel Beyond the West by Lamin Sanneh

One of Sanneh’s easily accessible primers on World Christianity is entitled Whose Religion is Christianity: The Gospel Beyond the West,[5] a dialogical text about the cross-cultural expansion process. He defines World Christianity as the wide variety of indigenous responses to Christianity as it takes shape in societies that had no previous bureaucratic tradition with which to domesticate the gospel. The process is distinctive. First, compared to Islam, Christianity does not have a fixed center or a fixed language. Second, the process of reception, appropriation, and reinterpretation is more significant than the work of missionaries, because the Holy Spirit works in this manner to revitalize the gospel and revitalize recipient cultures. These matters are easily taken for granted; yet, in the environment in which Sanneh’s work grew, Christianity was alleged to be a foreign religion in non-Western countries. He and scholars such as Andrew Walls and Brian Stanley have helped scholar-theologians navigate the postcolonial moment. This underscores the task of the theological scholar in our time: to discern how the animating issues in the present sociopolitical realm connect with what Hervieu-Leger refers to as chains of memory—the expression of believing and belonging within a much larger reality than immediately discernible in current context and experience, and the memory of continuity within the expansive community of faith.[6] In so doing, theological scholars should guide Christian communities to discern the signs of the times, like the sons of Issachar (1 Chron. 12:32) who understood their times and knew what Israel needed to do before advancing God’s redemptive purposes.

He defines World Christianity as the wide variety of indigenous responses to Christianity as it takes shape in societies that had no previous bureaucratic tradition with which to domesticate the gospel.

Along this track I find the theme of translation useful in rethinking the continuing expansion of Christianity in our day. In Megachurch Christianity Reconsidered: Millennials and Social Change in African Perspective,[7] I use Sanneh’s translation theme to arrive at a fresh appraisal of megachurches in our world. Sanneh’s translation principle helps to show that megachurch type of Christianity is thriving because it is making the gospel intelligible—freshly translating the gospel—to the metropolitan and cosmopolitan demographic. Whether they know it or not, megachurches are re-enacting translation to a vastly changed world, thereby creating a home for a generation that would otherwise feel homeless in a rapidly changing world.[8]

Readers of Sanneh’s other varied works are inspired by his deep inquiring mind, his subtle humor, his wide-reaching historical inquiry, his anthropological knowledge of the local cultures of his experience. All converge into this rich repertoire of social and theological insight that enables him to assess the contemporaneity of a whole range of issues and personalities that frame the interaction of the Christian religion with the world. This, in fact, is the essence of the study of World Christianity, a field he and Andrew Walls have pioneered. As an interdisciplinary field, World Christianity is cultivating insight into processes of conversion, transmission and translation, appropriation and reception of Christianity all over the world.

Promoting Muslim-Christian dialogue

Beyond Jihad: The Pacifist Tradition in West Africa Islam, by Lamin Sanneh

Another significant trajectory of Sanneh’s work involves Muslim-Christian dialogue in Africa.[9] Sanneh was born and raised to a Muslim society, and even after he converted to Christianity, he retained strong relationships with Muslims, commoners, and scholars alike. Several of his books have moved discourse about Christian-Muslim relations in Africa from assumptions rooted in competition, rivalry, and conflict. Sanneh shows how the two religions have historically engaged in a creative dance in west Africa. In Beyond Jihad: The Pacifist Tradition in West Africa Islam,[10] he argues that, contrary to the perception that Islam spreads by violence, historical inquiry shows that Islam has been successful in Africa not because of its military might but because it was adapted by Africans through the agency of pacifist clerics, scholars, healers, and Islamic teachers.

A witness in his time

Abraham Heschel in his 1962 classic, The Prophets,[11] writes that in the common imagination, we think of prophets as people who foretell the future, who warn of divine punishment, and who demand social justice. Yet core to their work is how the totality of their impressions, thoughts, feelings, and their whole being becomes a voice and vision that sustain the community’s faith in God’s current and ultimate involvement in history. Prophecy too, is not merely the application of timeless standards to particular human situations, but also an interpretation of a particular moment in history, bringing a divine understanding to human situations. Such a man was Lamin Sanneh, a witness in his time. When faith in cross-cultural mission work was on the verge of being shattered by cynical scholarship, his deep dive into the subject brought a bold and irenic appreciation of mission history as the hand of God at work after all, and that recalibrated the faith of many to re-engage vigorously in practical work of witnessing to the kingdom of God in our day. As we anticipate new challenges for the faith, may we too borrow a leaf from this man that now rests with the cloud of witnesses, and be witnesses of our own times.

Endnotes

- ‘About The Sanneh Institute,’ The Sanneh Institute, accessed 28 January 2020, https://tsinet.org/history

- Lamin Sanneh, Translating the Message: The Missionary Impact on Culture (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1989).

- Lamin Sanneh ‘Christian Mission and the Pluralist Milieu: The African Experience’, Missiology: An International Review, Vol.XII, No.4 (October 1984).

- Lamin Sanneh, ‘Disciples of All Nations: Pillars of World Christianity’, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

- Lamin Sanneh, Whose Religion is Christianity: The Gospel Beyond the West (Grand Rapids: William B Eerdmans, 2003).

- Danièle Hervieu-Léger, Religion as a Chain of Memory (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2000)

- Wanjiru M. Gitau, Megachurch Christianity Reconsidered: Millennials and Social Change in African Perspective (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2018)

- Editor’s Note: see article by Kwabena Asamoah-Gyadu, entitled, ‘Megachurches and Their Implications for Christian Mission,’ in September 2014 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis, https://lausanne.org/content/lga/2014-09/megachurches-and-their-implications-for-christian-mission.

- Editor’s Note: see article by Ida Glaser, entitled, ‘How Should Christians Relate to Muslims?’ in May 2017 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis, https://lausanne.org/content/lga/2017-05/christians-relate-muslims

- Lamin Sanneh, Beyond Jihad: The Pacifist Tradition in West Africa Islam (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016).

- Abraham Heschel, The Prophet (New York: Harper & Row, 1962).

Photo credits

Feature image from ‘Professor Lamin Sanneh: In Memoriam‘ by CSWCEdinburgh.

Feature image from ‘Lamin Sanneh‘ by Caorongjin (CC BY-SA 4.0). Description: Professor Lamin Sanneh at the Yale-Edinburgh Conference. Photo cropped and levels adjusted.