Going disrupted

We are in a decade of reforming mission strategy as new realities create both obstacles and fresh opportunities. Changing demographics and people movements compel us to rethink how and where to deploy kingdom workers whose very nature warrants reconsideration. Examining who is going where reveals immediate possibilities for revamping key aspects of mission strategy. Empowering believers already on the move to be frontline kingdom workers is essential in influencing nations for the gospel. In this article, we examine where these workers could have the greatest impact.[1]

LMS Missionary

David Picton Jones

There is much to learn from mission history. In 1884, LMS missionary David Picton Jones[2] lamented his inability to cross cultural and class divides with a local Uguha population in Central Africa that gravitated to the ways and religion of Zanzibar Muslims whom Jones employed as servants. The Africans and the European were neighbours that inhabited different worlds. Jones’ enlightenment view of man and the professionalism of the missionary endeavour prevented him from seeing the gospel operative in any other framework. For Jones, there was no real possibility of identification with the locals in life or spirit, so he rid himself of the Muslim servants. What would have happened had he changed his approach and employed Christian Africans from elsewhere?

Much of modern mission operates within similar frameworks that can create communicative gaps rather than bridges. As with all organisms, the missionary organization clings to that which brought it to life and finds it difficult to imagine alternate paths. Its systems and processes are designed to preserve its life and enhance, not challenge, its identity and purpose. Although widely considered a success, the traditional missions model is evidencing the certain approach of its demise, lacking agility and re-orientation in a rapidly changing world.

A key aspect of the missionary task is moving people from one place to another.

Political realities, particularly the hardening of borders to traditional missionaries and methods, are consuming more resources but yielding fewer breakthroughs. We would dishonour the heroes of the past by simply emulating them without adapting for today. As they did their best with what was given, we must do likewise with a different set of conceptual, political, and even technological tools.

A key aspect of the missionary task is moving people from one place to another. People movement across borders will continue. As the COVID-19 pandemic spreads, the push and pull factors at play will be exacerbated. The number of migrants in 2021 has receded due to border shutdowns, loss of migrant jobs, cross-border travel restrictions, and shuttering of economies. This exact moment feels analogous to the receding tide prior to a tsunami landfall. Massive economic damage across continents will create conditions for even greater mobility. Pandemic related conflict, economic parrying between nations, and civil disruptions will generate movement.

Where are the people?

How do we adapt our approach amidst these factors? Some churches have shown how effective migrant believers can be in the mission effort. Our experience as a mission with workers in least reached zones has shown that the hardening of borders for traditional mission work is accelerating.[3] How can we refashion our workforce to continue to push into these zones? OM’s internal group, Scatter Global, which is focused on mobilizing Jesus followers to least reached areas while fully engaged in their vocational pursuits, commissioned a study of existing people flows.[4] Of the 240 million migrants recorded in 2019 by the United Nations, how many might be evangelical believers? [5] If we were to focus on activating evangelical migrants to live as Great Commission Jesus followers, what prioritised zones could be affected? Of existing people flows, how many believers are going to least reached geographic zones? If sending professional missionaries to these regions is getting more difficult, are there natural people flows of Jesus followers to these regions that could be harnessed for incarnational mission?

We took the 2019 UN migration data[6] and superimposed Joshua Project information[7] to estimate the number of evangelicals that are likely part of the migrant stock. We assumed that the general population rates could also apply to migration populations, but there could be sub-populations like Jews returning to Israel, or persecuted Christians migrating because they cannot find work locally. Thus, the data should be viewed as more illustrative than actual. However, we are comfortable enough with the results to make some conclusions. Here is what we learned.

Most people live within narrow migration corridors usually tied to language, culture, and natural links between countries.

We noted roughly three million evangelicals[8] work in least reached countries. This dwarfs the number of full-time missionaries present there. The migrants may lack the theological training of full-time workers, but certainly have a similar spiritual reality as the first-scattered Christians in the book of Acts, and greater face time with indigenous populations.

Most people live within narrow migration corridors usually tied to language, culture, and natural links between countries. There is truth in the adage ‘from everywhere to everywhere’ but ‘from somewhere to a few nearby places’ is a better description of people flow. A strategy based solely on migrant believers would be insufficient as there are vast areas where there are no such populations. Many countries send workers into ‘Christianized’ zones. Here, efforts must focus on activating locals to engage the various diaspora. In Canada, from where I (Harvey) write, they are the colleagues, fellow students, and neighbours of our parishioners. Discipling local believers to be frontline kingdom workers is critical in reaching into the heart of far flung geographies, as every Somali in Canada is a ‘Whatsapp’ call away from an unreached village in Somalia.

Some “least reached” countries need to pursue other solutions

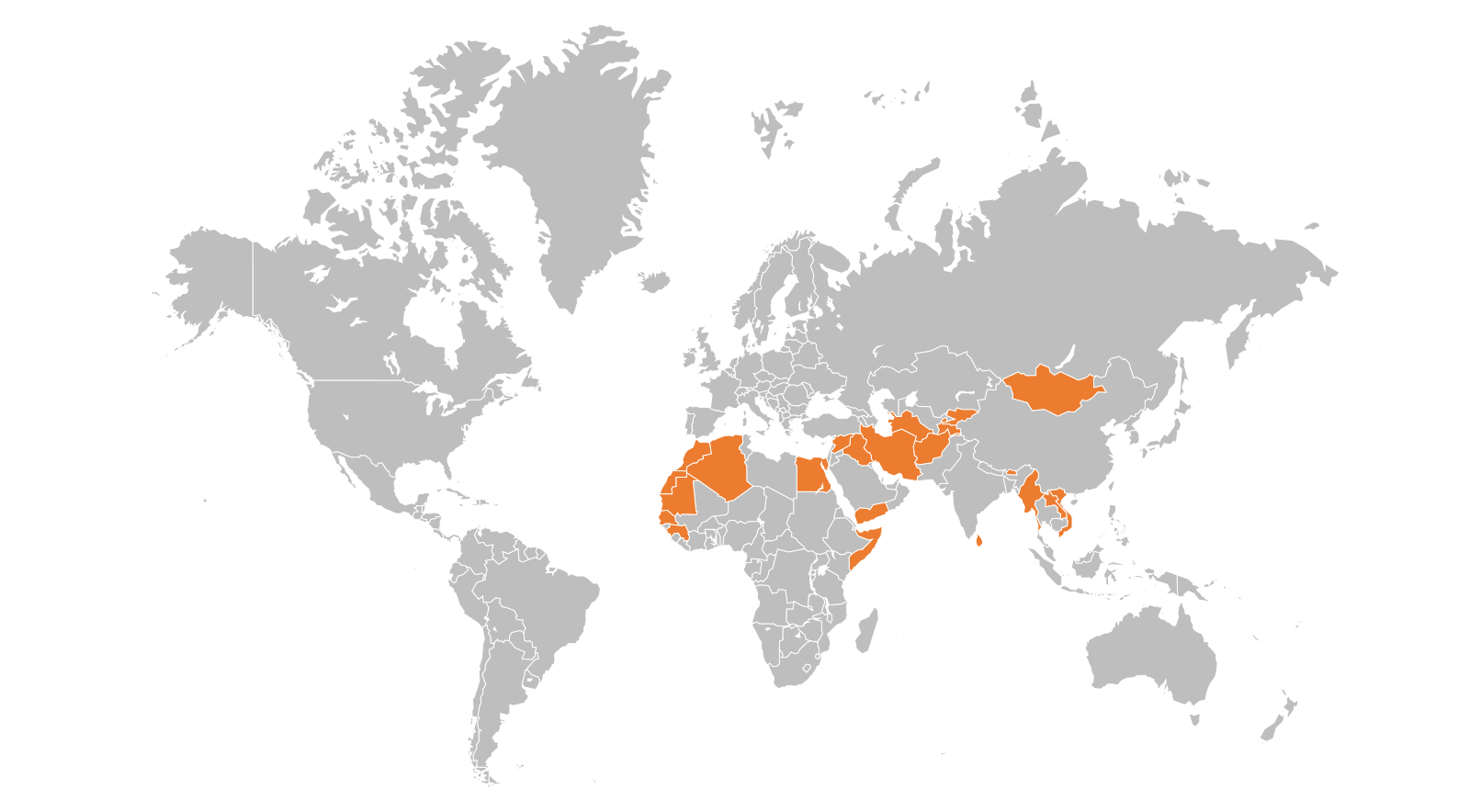

Host less than 5k evangelicals: Palestine, Egypt, Somalia, Tajikistan, Yemen, Myanmar, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Senegal, Guinea, Laos, Iraq, Cambodia, Vietnam, Iran, Bhutan, Gambia, Mongolia, Mauritania, Afganistan, Morocco, Syria, Sri Lanka, Tunisia, Algeria

Together they host ~1.5% of EM

Figure 1- least reached with minimal number of evangelical migrants

Ninety percent of evangelical migrants living in least reached places are concentrated in 15 countries. This gives a significant foothold in some very strategic places, but also highlights how some countries really are bereft of gospel influence.

~90% of EM live in 15 countries

Host Country

# of EM

% Global

Saudi Arabia

339,342

11%

Italy

331,973

11%

Germany

276,906

9%

France

261,314

9%

Japan

253,722

8%

Russia

242,717

8%

UAE

230,920

8%

Thailand

133,942

4%

Sudan

123,228

4%

Malaysia

106,818

4%

Bangladesh

97,632

3%

Kuwait

80,200

3%

Israel

64,561

2%

Qatar

60,998

2%

Kazakhstan

57,564

2%

Total

2,661,837

89%

Figure 2 – 90% of Evangelical Migrants live in 15 countries

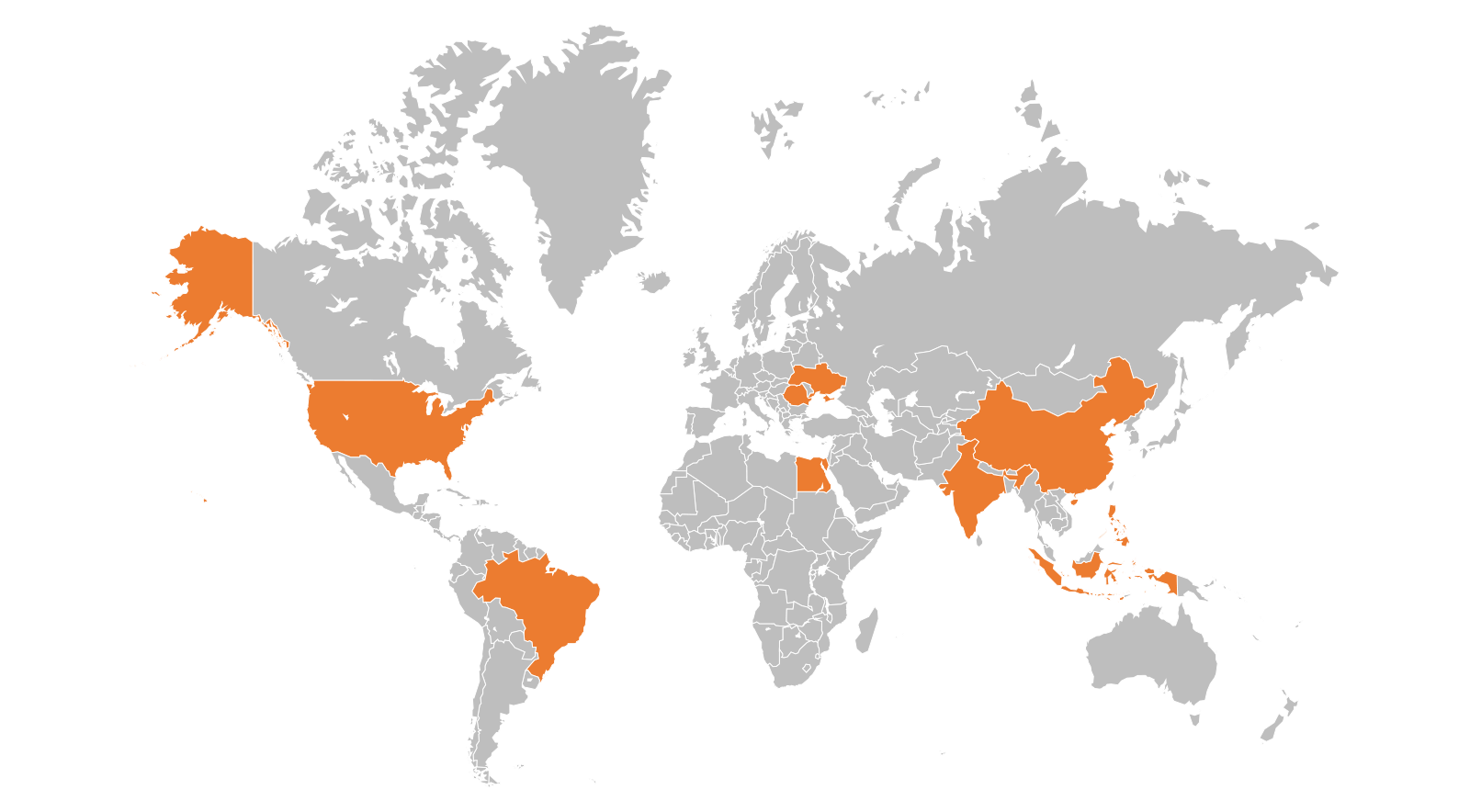

Less than 10 countries provide sizeable movements of evangelicals to prioritized zones; we should focus our attention there. We can collaborate with local churches to turn migrant population statistics into ‘called kingdom workers’. Growing numbers are already doing this because, unsurprisingly, people encountering Jesus generally get the idea that we are expected to share our faith. Obedience and skills are another matter.

Top 10 Sources of EM to all Least Reached

Source

# of EM

%

Philippines

304,295

18%

India

257,024

16%

Myanmar

169,081

10%

Ukraine

160,127

10%

USA

154,573

9%

China

139,427

8%

Egypt

123,715

7%

Romania

118,584

7%

Indonesia

117,801

7%

Brazil

110,961

7%

Figure 3 – Top 10 sources of Evangelical Migrants

Many of the evangelical migrant populations come from places viewed as ‘receiving’ fields. Foreign missionaries should be careful not to instill a view of the local church as the end product of missions. Rather, together with local Christian leaders, they must examine where the Holy Spirit is taking members of their congregations and view them as de facto kingdom workers. Then, a new commissioning can take hold bringing a fresh enthusiasm, sense of calling, and purpose to the church. This certainly applies to the former ‘receiving’ fields of the Philippines, China, Egypt, Brazil, Romania, Indonesia, Myanmar, and India—all of which are now sending powerhouses. Believers from these churches must know that they are not the finish line of missions, but a runner on the relay team that must both receive and pass on the baton. With such a view and calling, much can be done to disciple, prepare, and care for a new flood of workers into these priority zones.

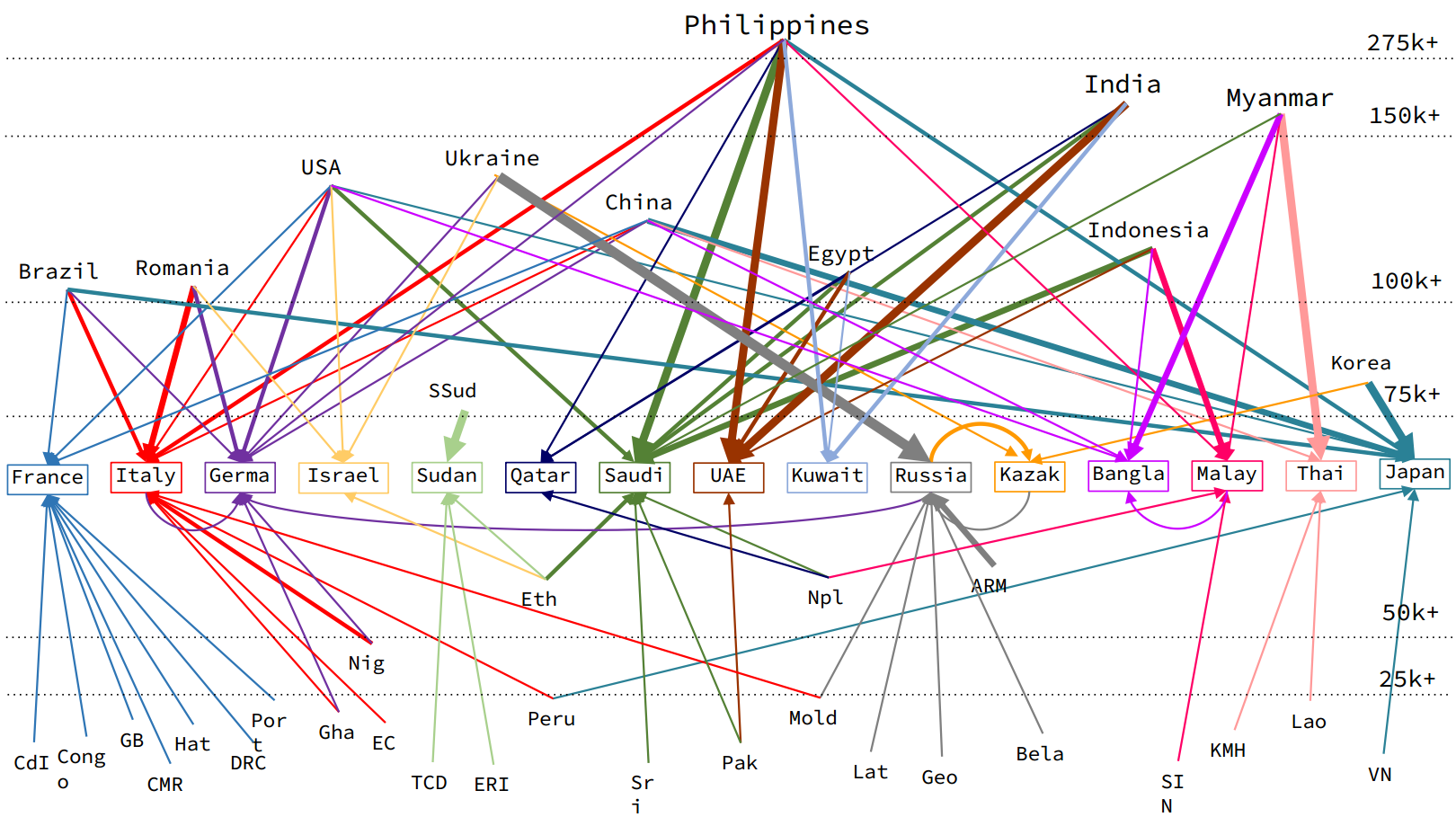

Top Sources and Destination of Migrants

Figure 4 – Top Sources and Destinations

Abbreviated country names used in graphic (in alphabetical order): Bangladesh (Bangla), Belarus (Bela), Cambodia (KMH), Cameroon (CMR), Chad (TCD), Côte D’ Ivoire (CdI), Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Ecuador (EC), Eritrea (Eri), Ethiopia (Eth), Georgia (Geo), Germany (Germa), Ghana (Gha), Great Britain (GB), Haiti (Hat), Kazakhstan (Kazak), Lao PDR (Lao), Latvia (Lat), Malaysia (Malay), Moldova (Mold), Nepal (Npl), Nigeria (Nig), Portugal (Port), Russian Federation (Russia), Saudi Arabia (Saudi), Singapore (SIN), South Sudan (SSud), Sri Lanka (Sri), Thailand (Thai), United Arab Emirates (UAE), United States of America (USA), Viet Nam (VN)

Activating the migrant flow

What is needed to strategically activate believers to engage fully in the Great Commission? Aside from the Filipino and Indian churches, there is little evidence of activation within other migrants. While believers instinctively find each other, they may not see themselves as commissioned kingdom workers. It is crucial that home churches see the potential and their responsibility. When the church realizes that their members are heading into an overseas situation that will put them face to face with unreached people, and these parishioners have the calling of God on their lives, new creativity, training, preparation, and support will be unleashed. Discipling them, endowing them with vision and formally commissioning them as kingdom workers, sent ones, will revolutionize how migrant workers see themselves and their role together with those that sent them. Many churches have felt insignificant, lacking resources to respond to the Great Commission.

However, it is this very lack of resources that is pushing church members into least reached zones and giving them opportunity to participate in the propagation of the gospel. We have wrongly coupled effectiveness of strategy with access to resources—those who have, can; those who have not, cannot. The downstream effect of this is that resource-laden individuals, groups, and peoples are considered more forward thinking, attuned with what God wants to do, and the most effective. The opposite may well be true.[9]

The Filipino church has been at the forefront of this effort in the last decades and has learned much in activating migrant workers. Their wisdom needs to be shared. Migrants face unique challenges and risks that need the support of both the home church and mission agencies that can curate their learning and pass it to others.

Mission agencies’ mobilization must include lay Christians among migrant streams. Training, evangelism resources, advice, venues to cooperate and more can mobilize and support them. We need the wisdom, organisational might, and commitment of the agency to forge new paths and seize new opportunities with new workers.

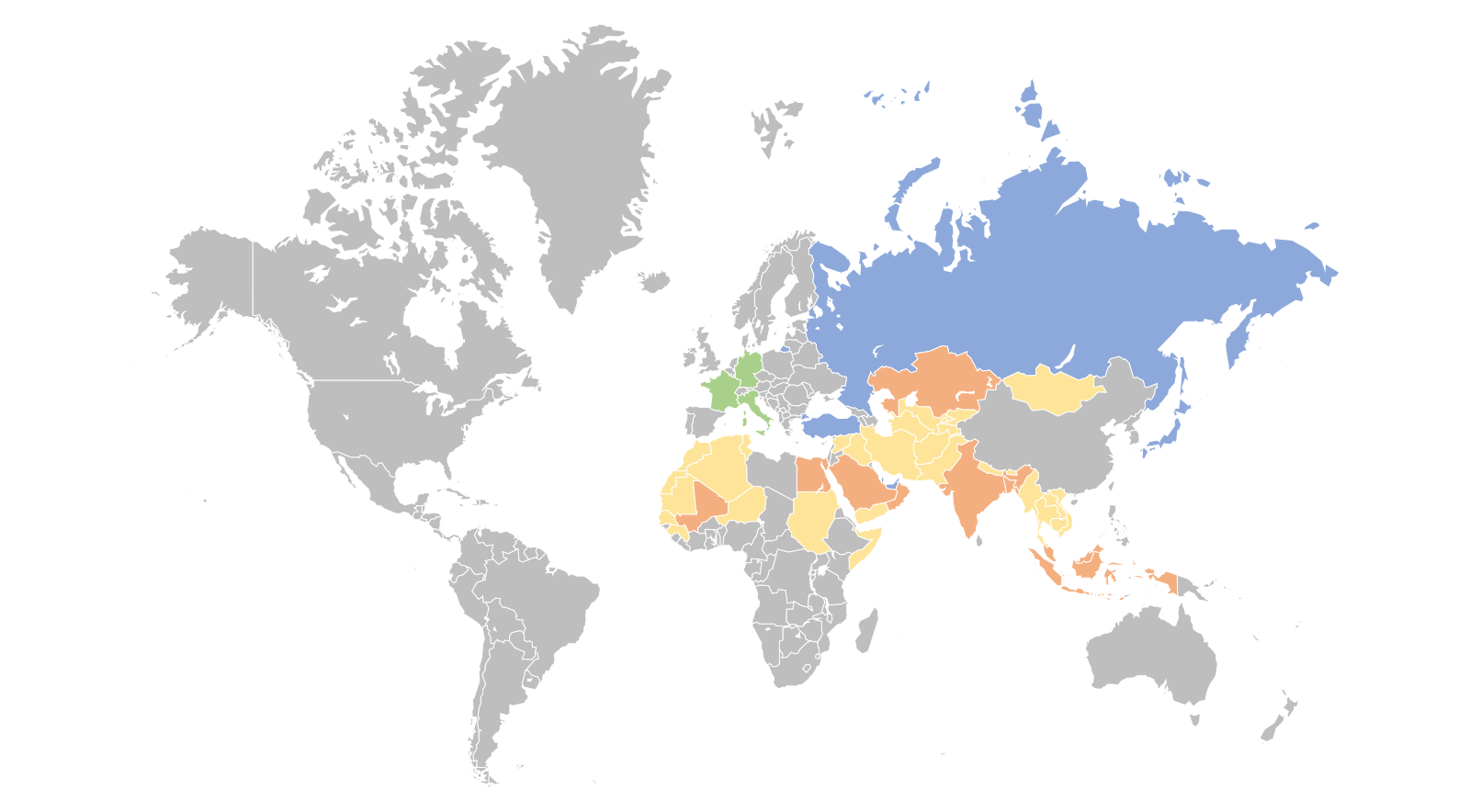

Europe hosts the largest diversity of all migrant sources

Figure 5 – Spread of EM in least reached zones

█ Hosts 80+ nationalities █ Hosts 20-36 nationalities

█ Host 10-19 nationalities █ Host <10 nationalities

Discipleship is key

We must focus on building mission vision in source communities.

The story of the average Christians’ worth and work as kingdom people needs revision. The secular-sacred divide has distorted the believer’s view of work. Pastors intuitively know that their role is to make disciples so that, wherever members find themselves, they know that God has placed them there to fulfil both their personal responsibility to care for family and to be his witnesses.

Migration patters will continue to change and need our attention. Our research has indicated very specific patterns of evangelical migration to high priority zones. This means that we must focus on building mission vision in source communities to use this opportunity. Yet, while the urgency of the gospel compels us to seek the best solutions, citius altius fortius is not the ultimate Christian principle. The Holy Spirit in disciples gathered in community anywhere means they have the power of the Creator within them and before them. He will bring all things to completion.

Endnotes

- Editor’s note: See article by Sadiri Joy Tira entitled ‘Diaspora from Cape Town 2010 to Manila 2015 and Beyond’, in March 2015 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis, https://lausanne.org/content/lga/2015-03/diasporas-from-cape-town-2010-to-manila-2015-and-beyond.

- Jonathan J. Bonk, The Theory and Practice of Missionary Identification,1860-1920 (Lampeter, Dyfed: Edwin Millen Press,1989), 54.

- Editor’s note: See article by Charles Rijnhart entitled ‘The World’s Least Reached Are On Our Streets’, in November 2020 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis, https://lausanne.org/content/lga/2020-11/the-worlds-least-reached-are-on-our-streets.

- Scatter Global, accessed 23 December 2020, http://www.scatterglobal.com/.

- Terms such as ‘evangelical’ and ‘least reached’ are as defined by the Joshua Project, https://joshuaproject.net/help/definitions.

- ‘Population Division: International Migration’, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations, accessed 23 December 2020, https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/index.asp.

- Joshua Project, accessed 23 December 2020, https://joshuaproject.net/.

- Limiting believers to this definition is not meant to exclude those from other Christian faith traditions who may not be formally associated with the evangelical church.

- Editor’s note: See article by Sam George entitled ‘Is God Reviving Europe Through Refugees?’, in May 2017 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis, https://lausanne.org/content/lga/2017-05/god-reviving-europe-refugees.

Photo credits

Portrait of David Jones from Wikipedia: David Jones (missionary)